The farmland fallacy: Why residential land will not be priced at agricultural value without planning regulations

And why this strange idea pervades housing economics

As always, please like, share, comment, and subscribe. Thanks for your support. You can find Fresh Economic Thinking on YouTube, Spotify, and Apple Podcasts.

Interested in learning more? Fresh Economic Thinking runs in-person and online workshops to help your organisation dig into the economic issues you face and learn powerful insights.

A recent economic report commissioned by the Housing Industry Association (HIA) assumed that in the absence of planning regulations, a block of land to build a detached home in Sydney would have a market price of $65,000 in 2025.

When one of us pointed out the absurdity of this assumption on X, HIA Chief Economist Tim Reardon replied as follows.

This is strange. There are many things one could do with a greenfield lot.

What economic theory says that the opportunity cost of a choice is an arbitrarily-chosen alternative and not the next best alternative?

There is none.

This is simply a mistake. But an extremely common one, with growing influence on policy.

We suspect the error began with Harvard’s Ed Glaeser, who is influential but far from rigorous in his economic approach. It’s hard to put a finger on precisely where he makes this assumption—pinning down Glaeser’s premises can be difficult—but ChatGPT has read his works, and when asked, “Does Ed Glaeser argue that land value for housing should reflect agricultural value but for zoning rules?”, it responds:

Yes, Ed Glaeser has argued that the cost of housing should, in a well-functioning market, largely reflect the value of land in its next best alternative use—typically agriculture—plus the cost of construction. However, he emphasizes that zoning regulations and other land-use restrictions create artificial scarcity, driving up housing prices far beyond what agricultural land values would suggest.

The idea that the price of land for housing should be something other than what it is—maybe the agricultural value, maybe the marginal value of a larger lot, maybe zero—is fundamental to Glaeser’s deregulatory agenda.

Here is a quote from the above podcast interview:

And so the core, like inside of our paper was, if it costs a whole lot more to buy something than it costs to build something, then something's screwing up this market, right? And all of our sort of early papers were about this, were basically like using the Chicago price theory thing, which is like, we can figure out how much it physically costs to build a unit, right?

Why doesn't it cost that much to buy a unit? Well, the only possible reason is we've got something that stops people from putting up more units. So this was done in our 2005 Journal of Law and Economics paper where we just said, look, the marginal cost of adding an extra unit in New York City is just the next floor, right?

The idea that residential land should be priced at farmland value has taken firm hold in New Zealand. Here’s a technical report stating this strange assumption. It says:

In the efficient market the cost (and price) of land for development is determined by the opportunity costs of supply of that land. Price is not determined by the higher value use of that land (residential vs agricultural). (p20, emphasis added)

The implicit assumptions here are that:

there exists a meaningful opportunity cost of supply for residential land,

this cost is equal to the value in agricultural use, and

with better policy, the land market could be made ‘efficient’, such that residential prices fall to the agricultural value.

Based on this logic, many studies now look at the price gap between similarly-located land zoned for either housing or rural use—a gap thought to represent how the price of residential land might fall if planning regulations were removed.

Here’s a NZ Treasury paper explaining the approach:

The urban fringe differential (subsequently called the ‘differential’) is a measure of the difference in price between urban and rural land at the edge of a city. It should help show the level of extractive land rents in urban areas. Land alike in amenity, once stripped of the value of infrastructure and buildings, should have a similar price whether it happens to be used currently for urban or rural purposes. Any difference in the value of the underlying land should therefore indicate the extent of extractive land rent – the rent extractable because of unmet demand for more urban development. (p17, emphasis added)1

NZ’s National Policy Statement on Urban Development (NPS-UD) requires councils to measure this differential on the basis that:

If the value of land jumps where the zoning changes, this indicates that various land-use regulations are constraining urban development capacity. The differential estimates how much urban residential land values are being elevated because of these regulatory constraints. (p144, emphasis added)

Commentators such as Eric Crampton have embraced this logic:

urban boundaries add over $600,000 to the cost of sections at Auckland’s fringes – and about $250,000 in Wellington. Those effects at cities’ fringes work their way even into the price of downtown apartments, pushing up housing costs across entire cities.

And this idea has also made its way to Australia. For example, this RBA speech noted that:

…in the absence of any restrictions on supply, the price of raw land on the fringes should be tied reasonably closely to its value in alternative uses, such as agriculture.

Shouldn’t land be priced at its opportunity cost?

Yes and no.

Yes, because competition between buyers can drive the price of land for any specific use up to the opportunity cost of that use, defined as the value of the next-best use. We explain how to interpret this idea below.

No, because competition between landowners can never overcome the inherent monopoly in land to drive the price down to the input cost of land use per se, which is zero. We return to this point at the end.

This two-part answer arises because unlike goods, services, and many long-lived physical assets, land has unique characteristics:

it is not produced, only traded,

there is a fixed number of locations,

and it has no input cost of use (i.e. nothing was given up to create the opportunity to put land to a positive value use).

Why is the farmland price assumption wrong?

To apply the economic theory of opportunity cost pricing to land used for housing, all we have to do is ask: “What is the next best alternative use?” Easy, right?

Maybe not. The closer you look at the concept of opportunity cost, the less obvious it is that it can be usefully applied to land prices.

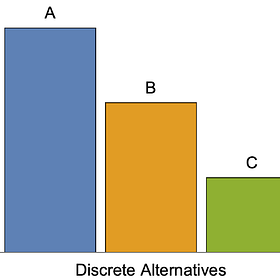

Consider the image below. It is the type of opportunity cost question one might see in an introductory economics textbook. If you could choose between just two alternatives, what would be the opportunity cost of the best choice?

As all students know, the opportunity cost is the value of the alternative. We can also see that the net benefit of the best choice over the alternative is a type of surplus for a person who has a higher-value use and buys it at a price reflecting a lower-value use.

For example, if one bidder at an auction was willing to pay the agricultural value and one bidder was willing to pay the residential value, the block of land would sell for the agricultural value.

At an English auction, where bids start low and rise until no one will bid higher, the market price is set by the second-highest valuation. Once the second-highest bidder stops bidding, the highest bidder need pay no more to win the auction, and the market price reflects the second-highest valuation.

Economic theory says that market prices under competition are set by opportunity cost—the second-highest bidder is the next best alternative in the market, so that’s the price at which the trade occurs.

Since the second-best use is agriculture, so the logic goes, greenfield residential land should be priced at agricultural value.

There are two issues with this logic.

The first is that the two-choice abstraction misses an important detail: in reality, there exists an infinite number of alternative choices, with many buyers who can try each alternative.

In the case of land, only the owner can develop it. But that owner can develop it in a wide variety of ways at many different times.

The second is that there is no good reason to expect agriculture to be the next-best (or equal value) use at the existing urban boundary or anywhere inside it.

We think that people schooled in the standard urban spatial model have been tricked into thinking that free markets will establish equality of residential values with farmland values since there must, in this model, exist some geographic location where the value of these two uses is identical.

But this idea can’t be extrapolated as a general rule at all locations, nor assumed to apply at the current (regulated) urban limit, as it is not the result of a causal opportunity cost relationship, but is just a coincidental point of overlapping bid curves.

To assume that the point of equality should be at the current urban limit, rather than somewhere further out, and that upzoning farmland will see residential land inside the limit fall in value to the farmland price, rather than land outside the limit rise to the residential value, is just wrong. It ignores the basics of land being priced as a bundle of rights.

Let’s unpack these two points.

More than one buyer, more than one alternative

The ECON101 opportunity cost example above is not a complete picture of the true alternatives for land nor how auctions work in reality.

Why are there only two bidders, each with one alternative?

The real world usually has more than one bidder prepared to pay the residential price. And each bidder might have a variety of land use alternatives in mind. Many bidders with many overlapping alternatives is the norm.

Which next best use of land should determine its market value?

Let’s consider this with the diagram below.

It shows a large number of alternative residential (blue) and agricultural (yellow) uses for any given location, ordered by value. One of these residential values might be the land value for a townhouse project, for example, while another might be for a small apartment building, another for a large detached home, another for a duplex built ten years in the future, and so on. One alternative might be essentially identical to the highest-valued option, but painted a different colour.

All of these are possible alternative residential uses. Each has a unique land value. So, which of these alternatives should set the residential value of land?

It must be the highest out of all of them. This is because the second-highest value choice from this infinite range of options is functionally identical to the highest.

The same is true for agricultural uses. There are many. In fact, there will be some agricultural uses with a higher value than some residential uses!

The reality of an infinite array of alternative uses is why one underlying principle in property valuation is to identify the highest and best use. This is the use that will determine the market value. Valuers recognise that the next best alternative will differ only infinitesimally, and that many potential buyers will face the same opportunities.

The idea of comparing the highest-value use within some category of use, such as residential, to the highest from within another category, such as agricultural, is arbitrary and unrelated to the real nature of competition between buyers.

If you’re not persuaded, consider the following:

Simplifying the alternative choices into farmland versus residential use implicitly takes as given that the value of each is in fact the highest and best use within each category—the highest value agricultural use versus the highest value residential use. The assumption that markets should price land at the value of the second-best use by category hides within it the opposite assumption, that the value for each category of use should be the highest and best use within that category. The possibility of alternative uses within a category is taken as given by those who compare housing prices to farm prices, yet not taken to its logical conclusion, which is that competition between buyers will bid prices up to the value of the second-best alternative within the highest-value category.

If the value of land truly were determined by the second-best category of use, then by simply prohibiting all categories bar one, say residential, the second-best category would contain no uses at all. If no industrial, commercial or agricultural uses were allowed, so the logic goes, residential land could be made to have zero value. But this is ludicrous. Locations are fixed in supply—so competition between buyers will always give land a positive value.

Development timing is part of the choice set

We haven’t yet talked about timing.

There is a particularly important next-best alternative when considering the choice to develop land into housing.

The choices a housing developer faces in the real world are not simply to build housing today or run a dairy farm forever. Nor are the choices limited to building townhouses today or apartments today (but only today).

Rather, the relevant alternatives are to build today’s highest and best use today or build tomorrow’s highest and best use tomorrow. Development is, at heart, a timing choice.

Developing land into housing means exercising an option to build: by paying the construction cost (the strike price), you receive the housing asset, but you sacrifice the option to develop in future. Taking as given that development, when it occurs, will be to the highest-value use, the ultimate alternatives are between exercising the development option now or preserving it for later.

What’s the value of preserving an option? It’s the market price of that option. So what’s the value of the next best alternative to sacrificing the option by developing land today? It’s the value of developing it at some future ‘tomorrow’. And this value is measured by the market price of land.

In other words, when we first set aside categorical thinking and recognise the myriad of alternative choices, and second recognise that development entails a timing choice, we can see there is only one logical way to define the opportunity cost of using land for housing: the opportunity cost is the price of the land.

That means the entire exercise of contrasting the price of land with its cost, so as to detect the signs of market or policy failure, and chalk these up to your preferred policy bogeyman, is flawed from the outset, for the opportunity cost of land for housing is simply the price of the land itself.

All those reports, all that data, are meaningless—grounded in a misunderstanding of opportunity cost. Goods and services produced from other inputs have costs that are independent of the value to buyers. Comparing prices to costs can tell us about efficiency. But land, which is not produced, has no such independent cost—only a price.

Why the confusion?

How did the apparent importance of farmland prices become so entrenched in the urban economics literature?

We think it is because the simplest economic theories of relative location and use value show that at some point of distance from a city centre, the highest value use from all alternatives will switch from one category of use to another—from commercial to residential, for instance, or from industrial to agricultural.

But this point is just a single location in a simplified one-dimensional model, as in the image below. As the distance from an urban centre grows, the value of using land for housing falls, while the value for agricultural uses falls more slowly, until at some point farmers will outbid residential buyers for the land. But this equality does not hold everywhere.

In fact, because there are many alternative residential and rural uses, this boundary could be very fuzzy in its location, varying based on soils and ground conditions, road networks, topography (residential on the hills and agriculture on flat land), and more.

Yet even underlying this location model of different uses (the Von Thünen model, if you want to look it up) is the idea that the value for each use is the highest and best use within that class of activity.

The model says that the highest-value user will always outbid other users for each location. It doesn’t say that lower-value uses will determine land prices at all locations due to being the next-best use that defines opportunity cost.

What about where regulations limit residential uses?

I’ve shown below how a gap between these two use values can arise when a regulation prohibits residential use at a location where it would otherwise be the highest and best use.

The existence of a gap does not imply that, in the absence of that regulatory restriction, land at that location would be valued at agricultural use value.

Instead, a regulation that prohibits higher value uses at that location from the array of legal alternatives will reduce the market value of the land. Land is a bundle of rights: add to the bundle, and the bundle rises in value.

The idea, prominent in the quotes above, that urban land values are made higher due to restrictions on rural land use, rather than rural values being made lower, is completely at odds with this idea. It is also at odds with the idea of a spatial equilibrium that equalises quality of life across cities.

Finally, note that price steps at zoning boundaries do not imply anything about the rate at which new housing is produced across all potential development sites. There is no grounding to claims that price discontinuities signal that housing production is being delayed.

Remember, the highest and best use might be developing homes today, or it might be developing homes in 10 or 20 years’ time. Markets always efficiently delay building feasible new homes, as we have explained. Price gaps due to regulation at specific locations are irrelevant to this question.

Price discontinuities simply signal that marginal differences in land use rights have some market value. They signal that existing regulations are binding on land-use and built-form outcomes at the site level, either now or in future. A planning system with no zoning boundary discontinuities is a planning system with no binding regulation whatsoever.

So what?

Assuming that land where housing can be built ought to be valued by the market as if housing cannot be built is bizarre.

This misuse of the concept of opportunity cost has crept into the analysis of housing markets, leading to poorly justified claims of inefficiency and misleading many as to what pricing outcomes are possible.

It has also obscured another and more intriguing land cost concept—not the opportunity cost of any particular land use, but that the input cost for land use per se is zero. In a classical economic sense, a price above the input costs of production indicates a surplus.

Looking at price-cost comparisons this other way reminds us of the obvious but often forgotten unique character of land—the inherent monopoly—and reminds us that the property rights we create over land are what give it a positive value at all.

Land prices are pure monopoly rent. It’s all a form of surplus.

There’s no good bit and naughty bit. It’s all excess profit, unearned and ‘extractive’. We simply cannot detect market failure or policy failure by looking at the price of land, because all we’re seeing is the logical consequence of a fixed stock of locations.

Yes, I have explained this before.

Do economists know opportunity cost when they see it?

Welcome to new subscribers. If you like this, please check out some of my other posts, such as:

And here are some more musings on why property has a market value at all.

Why aren’t land titles free?

When it comes to debates about housing supply and prices, some people, especially economists, argue that the land market can be price competitive. Only regulations stop this. Harvard economics Ed Glaeser has made a career arguing it.

More on delaying building feasible new homes.

Explainer: Markets efficiently delay building feasible new homes

Note: Monthly FET subscription prices are rising for new subscribers. This is intentionally to make an annual subscription much more attractive. Current monthly paid FET subscribers are unaffected and will always keep their original price. Yearly prices remain unchanged.

The term extractive rent is not used as a synonym for land rent (the monopoly rent of land). The Treasury has developed a novel theory that markets for land—which Churchill called the “perpetual monopoly, and the mother of all other forms of monopoly”—can in fact be made ‘competitive’. In this framework (see here and here) there is good rent and bad rent: differential rents are due to desirable locations being in fixed supply, and extractive rents are a premium above this which could be eradicated with better policy. We’ll discuss the many issues with this idea in a future column. The problem in brief is that lower land values would not be an equilibrium in either consumption share, asset pricing or locational choice markets.

The clearest parts of this paper for me are that land is in fact valued at its highest and best use, that is way the market works, and that values for residential use tend to decline with distance from an urban centre, even without regulation. However, it is important to note that the latter is complicated by the fact that many urban regions are multi-centred and also by the fact that lot sizes tend to affect land values because solely/largely residential use is nearly always an option. Except in the case of very high value/intensive agriculture or horticulture, much rural land within the sphere of influence of major urban centres is at best used for part-time farming, and often only for 'rural living'. That is certainly the case for land with slopes and/or relatively poor soil such that it would otherwise only be used for grazing. Even quite large lot sizes, say 40 hectares, can be devoted to rural living as the highest and best use, particularly once improvements are made for large houses, etc.

Another couple of points:

# even without regulation, areas closer to existing urban development would tend to be valued higher as having better prospects for extension of necessary urban infrastructure in the future, at a feasible cost

# the feasibility of urban development on any site is partly dependent on the extent to which it might logically link in to existing or planned or prospective infrastructure on nearby land - so you can't consider the value of any individual site without looking at its context/catchment. This also tends to necessitate some degree of complementary/joint action/choices for a particular area to make urban development feasible - through some combination of a major master planning developer, a joint private venture and/or governments allocating the area to urban development and supporting the provision of infrastructure to it.

Great article. My only recommendation would be to explicitly link and reference Mason Gaffney. He wrote A LOT about why land is different from capital, and why assuming that it is just another form of capital will systematically blind economic analysis, in favour of landowners. Just a small shout-out and link, so people who want to go deeper can, and to show that your points aren’t drawn out of thin air, but backed by a long and well established line of economic reasoning.

The too-long-didn’t-read version: https://www.cooperative-individualism.org/gaffney-mason_land-as-a-distinctive-factor-of-production.pdf