Ed Glaeser: Harvard's housing huckster

His absurd housing analysis makes you wonder if he knows anything about housing markets at all

Academia is often a social status game more than a knowledge production game.

Everybody knows this. But few say it.

Everybody knows that there are clueless experts. But few say it.

So today, I’m going to say it.

If what Harvard Professor Ed Glaeser writes about housing markets reflects his understanding of them, he is a clueless expert.1

This is a guy with hundreds of academic articles on property markets. His body is a machine that converts money into academic papers. But what about knowledge?

I want to change the social status game and be the first mover to call out this poor economics. I hope others will feel more comfortable doing the same.

Today, I’m going to explain the ridiculous problems with the economic analysis in his 2018 paper in the Journal of Economic Perspectives with Joseph Gyourko entitled The Implications of Housing Supply.

It’s not the first time I’ve called out his dodgy analysis.

I spent many years trying to get people to see the problems with one of Glaeser’s other famous but useless methods for analysing property.

But social status games dominate. This was made clear by the comments I received from an anonymous reviewer about my paper critiquing Glaeser’s analysis.

The main point of this paper is both correct and important: the popular hedonic price method of calculating a "regulatory tax" initiated by Glaeser and Gyourko (2003) (henceforth G&G) has little or no scientific merit, and should not be used.

...So the G&G method is ripe for criticism. The early critiques by Somerville (2005) and O'Flaherty (2003) were massively ignored, and their authors probably didn't notice because they thought that the G&G method was too ditzy to go anywhere. But as Murray points out, the method has become popular and its results have become influential. So Murray's critique is timely.

But it has to be rewritten. G&G have both done a lot of good work; this strand of literature is really an aberration. So the profession's prior is that G&G are right and Murray is not. To move the prior, Murray has to be both succinct and serious: succinct because nobody is going to start reading a long paper by someone they think is a kook, and serious because Murray must prove himself part of the brotherhood, not an outsider or rabble-rouser.

If ignoring status games because you want to understand the world and gain knowledge is rabble-rousing, then so be it.

And I strongly disagree with the reviewer that Glaeser’s previous dodgy analysis was an “aberration”.

Glaeser and Gyourko’s 2018 article claims to review “the basic economics of housing supply and the functioning of US housing markets to better understand the distribution of home prices, household wealth, and the spatial distribution of people across markets.”

It does nothing of the sort. Below, I explain why in detail.

I am confident that most people who understand housing markets think this paper is silly and wrong, but aren’t willing to say it. Maybe people think you need status to call out a well-published and cited Harvard professor.

But knowledge production doesn’t care about status, even if academic careers do.

I’m sure some people will respond to this Fresh Economic Thinking article with more status games: “You don’t understand Glaeser’s model”, and “Are you really saying a Harvard professor doesn’t know his stuff?”. These are not arguments. And I don’t expect to hear any arguments, as there are no arguments in favour of this absurd economic analysis. When I posted about this poor analysis on X/Twitter, no one defended it.

Absurdities in his housing analysis

Let’s go through the major errors of logic and reasoning in The Implications of Housing Supply paper by Glaeser and Gyourko. As a quick summary, Glaeser and Gyourko assume in this paper that in an unregulated market, cities will only have detached housing and that every home in every city will have the same market price which is always construction cost multiplied by 1.4625.

Absurd, right?

1. Theoretical issues

The underlying theory relied on in the paper is that there is an independently determined thing called a minimum profitable production cost (MPPC) for a single detached dwelling.

The ratio of the market price of a home (at a location) to this MPPC production cost of a home is thought to capture the idea of Tobin’s q, and that “regulatory construction constraints can explain why this variant of q may be higher than one”.

So, according to their argument, if the market price of a housing asset is above the cost of producing the home, or q >1, this indicates a regulatory barrier.

They write:

Specifically, we investigate whether market prices (roughly) equal the costs of producing the housing unit. If so, the market is well-functioning in the sense that it efficiently delivers housing units at their production cost.

And:

The gap between price and production cost can be understood as a regulatory tax, which might be efficiently incorporating the negative externalities of new production, but typical estimates find that the implicit tax is far higher than most reasonable estimates of those externalities.

To give an example, imagine if it cost $25,000 to manufacture a caravan (including a profit margin) and the market price of caravans (new and second-hand) was $50,000. The q ratio of market price to production cost would be two. Glaeser and Gyourko would argue that this ratio can only be sustained if there is a regulation acting like a quota on new homes that stops new caravans from being produced to push prices down to $25,000 across the market.

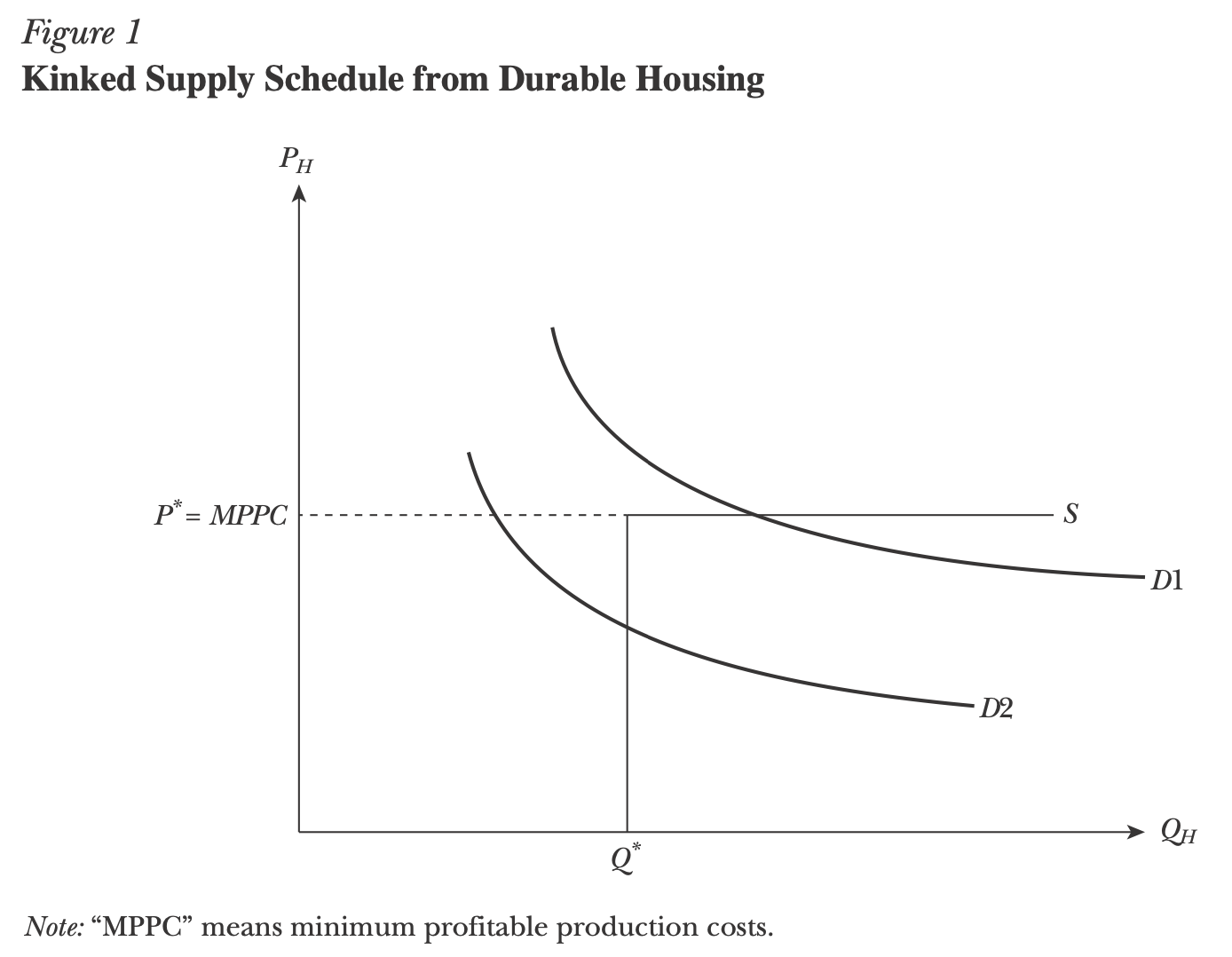

This is a restatement of the usual quantity and price equilibrium of the stock of homes in a city, but with the additional assumption that building faster has no diseconomies of scale—the supply curve is just a flat line at this MPPC.

In short, the theory amounts to “whatever I decide is MPPC is what houses should cost, and any other price reflects a regulatory cost.” The diagram below from the paper makes this clear. This is quite a huge claim from someone who appears otherwise enamoured about how flexible markets are.

Hidden in this theory is the idea that since construction costs are assumed to be the same in all cities, the housing prices should also be the same. The theory assumes away agglomeration economies. They assume, against all experience, that all cities will converge to the same house price regardless of income differences.

The theory is heavily laden with assumptions that only make sense for mobile goods like caravans, but it ignores all the important features of locations and property rights to those locations that are the main issue with housing.

2. Assuming away location value in production cost

So we have a theory of market prices for homes in different cities, which boils down to simply assuming that all homes in all cities will be priced at whatever Glaeser and Gyourko decide MPPC (cost) to be.

So what did Glaeser and Gyourko decide is their MPPC?

They decide that MPPC can be independently determined by only knowing construction costs (CC) and making two assumptions about:

How much land should cost (L)

How much profit margin is needed to get homes built (entrepreneurial profit, EP)

They assume MPPC this way.

Basically, you add up an assumed cost of land to the construction cost, add a profit margin, and that’s the minimum profitable production cost (MPPC).

Strangely, the land cost is assumed to be 25% of the construction cost.2 Here’s the explanation:

Vacant land sales are rarely observed in the United States, so to estimate the value of a price of land, we use an industry rule of thumb based on an ad hoc survey of home builders that land values are no more than 20 percent of the sum of physical construction costs plus land in a relatively free market with few restrictions on building.

For a start, valuing vacant land is not so difficult. Australian states value every plot of land in the country routinely.

Anyway, the pivotal assumption here relies on an “industry rule of thumb” based on an “ad hoc survey”. Sounds a lot like “I asked some mates”. Which is fine, I guess. But a weird way to assume away land value variation.

They then assume that entrepreneurial profit is 1.17 (i.e. a 17% margin).

What the combined assumptions mean is that if the construction cost is $100,000, the land input cost is assumed to be $25,000. And then this total of $125,000 is multiplied by 1.17 to give the $146,250 as the MPPC.

Their numbers are $85 per square foot construction cost, with 2,000 square foot homes, to get a $170,000 construction cost. Then you add the assumed land cost of $28,400 (170,000 x 0.25) and multiply that total by 1.17. This gets $248,625 as the MPPC on average. They say:

This suggests that an efficient housing market should be able to supply economy-quality single-family housing with 2,000sq ft of living space for around $200,000 in low construction cost markets and for little more than $265,000 in the highest construction cost markets.

To be clear, the net effect of these assumptions is to just assume that the MPPC is construction cost multiplied by 1.4625 for an assumed size, type, and quality home.

We can rewrite their assumption of the cost of homes as

That’s it. And now they have assumed away the relative value of land of different locations in different cities.

To show the absurdity, you can build the same home in a high-value location and a low-value location—whether that’s Sydney and Singleton, Boston and Buffalo, Seattle and Spokane—with the same MPPC, but with a radically different market price.

In Singleton, a home with a construction cost of $300,000 has an MPPC under these assumptions of $438,750. That might be around its market value in Singleton. But build that $300,000 construction cost home in Sydney, and the market price will be $1 million or more.

According to these assumptions, the only way homes can have different market prices in different cities is because of regulations. Sydney and Singleton must have the same market price for the same dwelling.

At best, the gap between this assumed MPPC and the market price is just a weird way to measure the relative value of different locations.

But Glaeser knows better. Land values should converge between cities!

We will also ignore amenity differences, so an absence of regulation will tend to equalize housing costs and wages across space

Has there ever been a point in history, even before planning regulations, where major cities had the same home prices as regional towns? It makes no sense. It is assumptions layered on assumptions, with no reference to spatial equilibrium and the relative value of locations and anything that looks like reality!

3. Ignoring the density and age of homes

Just as it makes no sense to assume that land value is a fixed share of construction cost at all cities and locations, it also makes no sense to ignore the different densities and ages of the housing stock.3

The method completely breaks down when we consider that attached dwellings — townhouses and apartments (condos) — are real things that exist in real cities.

In cities and regions with attached housing, it is not clear why you should be able to produce new detached homes at their construction cost. If the price of detached homes were their construction cost, there would never be an incentive to build higher density, as the price of higher-density homes would be below their construction cost.

For apartments to exist in a city, the market value of detached homes must exceed their construction cost.

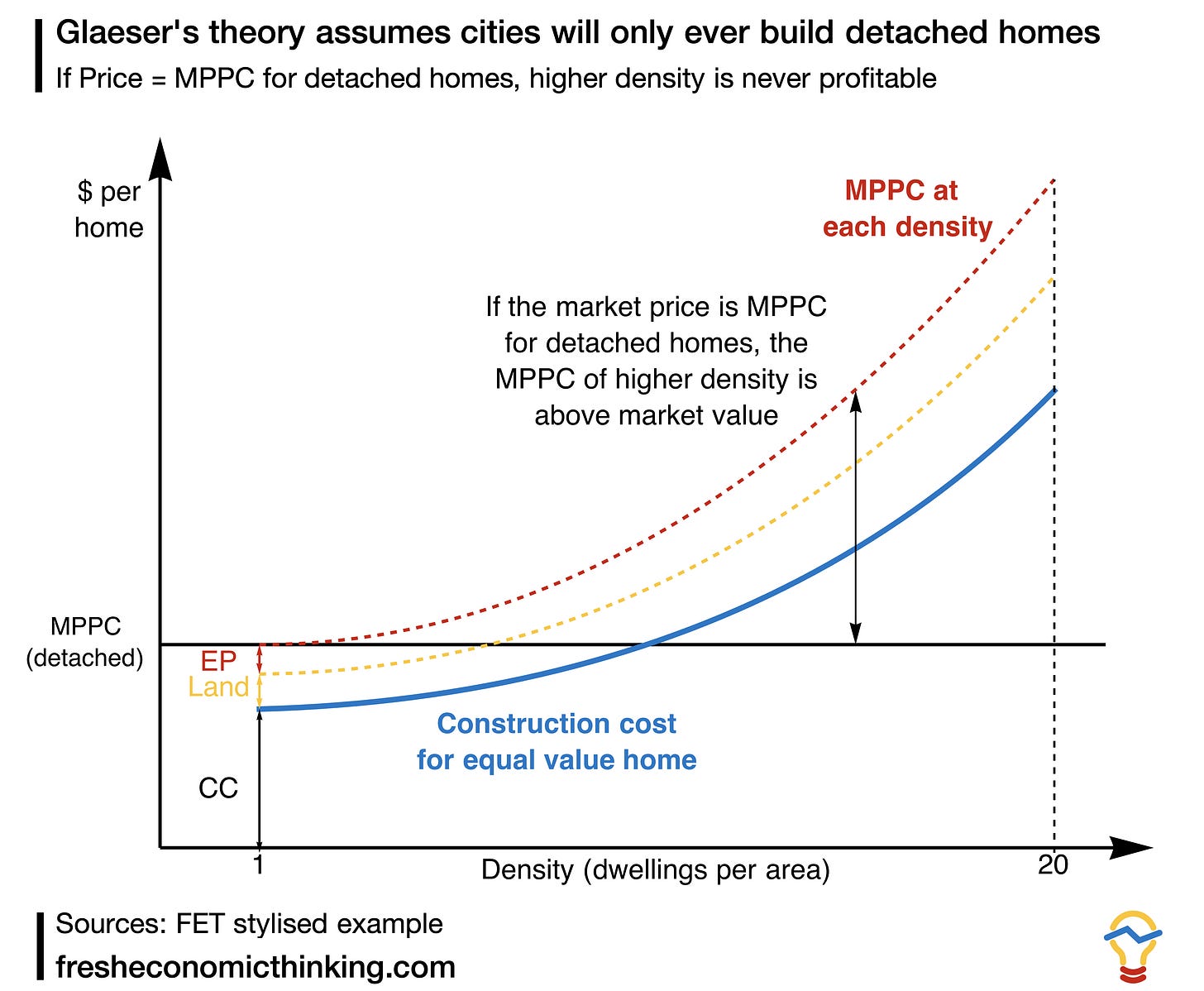

Let me use the diagram below to clarify this point. The blue line is the construction cost per square meter of an equal-price home (i.e. you will need a higher-quality townhouse to fetch the same price as an equally sized detached house, and so on. Think of this as a construction cost for a $1 million dwelling at different densities). Construction cost rises with density for a dwelling with an equal market value.

Now, if we apply the MPPC process to this construction cost across all densities, we get the dashed yellow line when we add the land price assumption (multiply construction cost by 1.25) and then the dashed red line when we add entrepreneurial profit assumption (multiply construction cost plus land by 1.17). So that total red line is construction cost multiplied by 1.4625.

This is the minimum cost for developing homes at each density, according to Glaeser.

Notice that each housing density has its own MPPC, which rises with density just as construction costs do for a dwelling with the same market value.

What we see is that if the market price of a detached house is the MPPC for a detached house, then every higher density of housing must be uneconomical to build because the MPPC for every other density is higher than its market price.

To reiterate, if the market price in a city is exactly what Glaeser assumes to be the minimal profitable production cost of a detached home, then no higher-density homes can profitably be built.

What this amounts to is that Glaeser and Gyourko embed an assumption in this paper that in an unregulated free market, cities will never build to higher densities than single detached homes. Every city will only have detached housing, and every home in every city will have the same market price which is always construction cost multiplied by 1.4625.

It’s absurd!

Why this matters

Policymakers and the chattering lobbyist class love Glaeser’s absurd analysis, which always shows that homes are the wrong price in wealthy cities.

He recently wrote in the New York Times about how the federal government should bully and bribe cities if they don’t meet arbitrary housing construction targets. All informed by the absurd ideas in this paper and others that a deviation of the market price of detached homes from 1.4625 times the construction cost in any city indicates a regulatory problem.

A similar policy is being promoted in Australia and Canada. Canada’s Conservative Party leader, Pierre Poilievre, has tabled a bill called Build Homes Not Bureaucracy, which has a very catchy name and is proposing to reward cities that increase housing construction rates by more than 15% per year.

Of course, this is absurd. Had that policy been in place since the 2021 dwelling permits peak of 300,000 in Canada, then this year it would require 434,000 new dwelling permits to reach that target. Had it been in place since 2014, then 550,000 would be today’s target.

The actual number was 265,000.

In 2031, 15% growth compounded for a decade would imply a target of 1.2 million permits in that year! Why does new housing need to quadruple every decade? Who is going to pay for these homes and live in them?

It’s all as absurd and arbitrary as saying that new detached homes in every city should be the same price of construction cost multiplied by 1.4625.

And it all ignores the fact that since 2022, countries around the world have been trying to stop homes from being built by tightening monetary policy!

But this is where you end up if you don’t call out absurd housing analysis and instead play the academic social status game.

Thank you to all the FET paid subscribers. Here’s a copy of a speech I made at the Anglicare conference in Newcastle last week, which I called “What’s right and wrong with housing?”

I wrote this before about whether what Ed Glaeser writes is any reflection of his understanding, or whether it is just a series of nice buzzwords— “When I read Glaeser’s writing I can’t shake the feeling that he doesn’t really believe what he says much of the time.”

That is, they assume that land value = 0.2 x (land value + construction cost), which rearranges to land value = 1.25 x construction cost.

On the issue of the age of dwellings and size of land, consider the following scenario.

The price of a 200 sqm dwelling will differ substantially if it is on a 300 sqm block of land or a 3,000 sqm block. By quite a lot probably. Since older suburbs often have larger blocks of land and are in better locations, data on market prices, even adjusted for dwelling size (not land size) will reflect not only different location values but the value at different densities.

Consider a city with two suburbs. One suburb is 50 years old and has 1,000 homes all 200 sqm in size on 1,000 sqm lots priced at $1.4 million, which is the premium location. The neighbouring new suburb has 1,000 homes and is growing rapidly, but the location is inferior. There, new 200 sqm homes are on 300 sqm lots and sell for $600,000, with a construction cost of $400,000. So in this city, the market price, on average is $1,000,000 and the construction cost is $400,000 for the same 200 sqm dwellings.

Using the MPPC method gives a production cost of $585,000, which is close to what new homes are sold for.

But the q ratio in this city is 1.71, with the average market price across the old and new suburbs of $1,000,000 divided by $585,000. All the older, lower-density homes are pooled in to get the market price. But looking at the new suburb, the ratio is 1.025 (or 600,000 / 585,000).

So in places where more of the stock is newer, lower density, and in more premium areas, you will get a higher ratio without any effect of regulation.

Your first problem is trying to read Glaeser literally.

Take him seriously, not literally.

A literal reading will drive you mad because his housing analyis is not designed for coherence. It is designed to hide the economic role of land as distinct from capital (i.e. as a factor of production fixed in supply and earning economic rents), to misidentify the effects of land speculation as consequences of poor regulation, and to pursue deregulation, all in order to provide financial benefit to land owners.

As per my NZAE talk, I believe that neither Glaeser nor anyone else who claims that regulation makes housing expensive has any coherent theory of housing supply.

None of them can answer the simple question "why are houses built?" with anything approaching a coherent explanation.

Ironically, they have many answers (rather, the same answer, given many times) for why houses are NOT built. Which is a really neat trick, because it turns their scientific inadequacies into a strength. If they can't explain why prices aren't lower and quantities aren't higher, because they don't have a theory that works when it comes to explaining the facts, it means they can blame their chosen villain, which is regulation. In this way, incompetence is a great hole to fill with ideology.

For the benefit of your readers, here are several related ways to describe the problems with almost all US literature on housing supply, including Ed Glaeser's work. They're a slightly different take on your column:

1. This entire body of work implicitly assumes that houses are built if and when (and because) there exist arbitrage opportunities in present-day prices. This is the totality of their theory of supply. Their theory is that if the price of houses exceeds the price of construction, construction will go ahead. By implication, they think developers and landowners are myopic (i.e. not forward looking). The process of housing development in their theory of housing supply is one of 'myopic arbitrage', where no developer looks beyond present-day prices when deciding whether to build housing. In other words, if construction is profitable today, then unless encumbered by regulation, construction will go ahead, because developers and landowners in this theory are believed to be not smart enough to realise that it might be even more profitable to delay construction until tomorrow. There is no forward-looking behaviour in this theory. By assumption, therefore, there is never any vacant land already feasible to develop (since all land is developed as soon as first feasible), and there is certainly never any speculation or land banking (choose your term: either way it means not developing housing despite the change of use already being profitable), and therefore there also is no reason for these economists to go looking for, let alone try to understand, these empirical phenomena. According to the old management cliche, "you don't value what you don't measure", but for US housing economists, a better version is "you don't need to measure what you don't acknowledge".

2. They do not appreciate that "construction cost" is not the same thing as "supply cost". In the real world, construction is only one of the opportunity costs of developing a new home. To supply a new home in the real world means giving up the option to develop that land differently in future. Sacrificing that option is a true opportunity cost of supply. The true cost of supply therefore equals the cost of construction AND the value of land options foregone. What is that value? It is identical to the price of land, as set by developers themselves, competing to buy that land in the knowledge that they will be able to sell houses for so much more than construction cost because land is physically scarce and land rents can't be competed away ("they ain't making it any more"). Glaeser wonders why house prices don't match his measure of production cost (MPPC). One reason is that he doesn't include the actual price of land as a cost of production. As you point out, Glaeser's MPPC just includes an arbitrary scaling factor, in lieu of actual land prices. And as you point out, this is only suitable for a world where all locations are identical and location services just happen to be worth 20% of the value of structure services.

3. They use metrics that are blind to history, specifically, the existence of buildings already on the site that are not yet worth tearing down. One of the most bizarre things about comparing house prices to MPPC as a measure of a "regulatory wedge" that drives up house prices is that, even setting aside my previous point, the true opportunity cost of production on any infill site also includes the loss of capital extant on the site. When you must tear down valuable capital in order to supply new housing, that entails an opportunity cost, namely, the present value of the services the existing building could provide with no further investment. In the real world, this value acts as a hurdle to supplying new housing. But it doesn't exist in the MPPC concept, nor in the "marginal cost of land" concept used in the Glaeser + Gyourko "average cost vs marginal cost" method used to "identify" the price effect of planning restrictions. That makes the MPPC and the AC vs MC concepts only useful for vacant land, which is something people replicating those methods in the Australian and NZ contexts are clearly blind to. One of my favourite quotes from Kendall and Tulip (2018) is this: "some barrier has to stop people subdividing properties at low cost and then selling them at high market prices. We discuss several possibilities... and conclude that the most plausible explanation is that subdivision is illegal in large parts of our cities". Could that barrier possibly, just possibly, be the fact there are already buildings on almost all of the land in the cities Kendall and Tulip measure in their data?!?

Ugh, Glaeser. It was hilarious for me, as someone who spent a lot of his career trading options and modeling options to read the 2018 paper. My first take was, hey, building on some land is exercising an option to develop. I'm an options trader. I know that it is not optimal exercise behavior to exercise any option the moment it goes one penny in-the-money. But that's what his analytical framework is based on! That's actually how I discovered Cameron Murray's work -- ran across his paper on the importance of considering land banking... Don't sleep on Gyourko either. The Wharton Residential Land Use Restrictiveness Index, which now pops up everywhere in the literature, is a hot mess. In my particular branch of finance, we do a ton of Principal Components Analysis, and the use of it to create the WRLURI is more like abuse. Taking the first principal component and making that your metric? OK, let's replicate it with their data. Hey, wait a second, some of the variables have loadings with signs the opposite of what theory (and common sense -- after all, we are talking about land use rules, not particle physics) would suggest. Oh, and he mixes dichotomous and continous variables in the PCA. I mean, just a friggin' mess. And now the literature is riddled with regressions where WRLURI is in the set of independent variables. Their work is like the PFAS of housing economics. Dangerous forever chemicals that get everywhere...