Why aren’t land titles free?

Because property is a monopoly

When it comes to debates about housing supply and prices, some people, especially economists, argue that the land market can be price competitive. Only regulations stop this. Harvard economics Ed Glaeser has made a career arguing it.

Our alternative view is that housing is expensive because of artificial limits on construction created by the regulation of new housing. It argues that there is plenty of land in high-cost areas, and in principle new construction might be able to push the cost of houses down to physical construction costs.

…this hypothesis implies that land prices are high, not due to some intrinsic scarcity, but because of man-made regulations. Hence, the barriers to building create a potentially massive wedge between prices and building costs.

At a more general level, the argument that property markets are competitive is made by Thomas Merrill in his chapter on private property and public rights (Chapter 4 of the Research Handbook on the Economics of Property Law), which is worth quoting in full.

A familiar economic argument for regulating private property rights is the prevention of monopoly. All property rights confer a monopoly, insofar as the right to exclude also gives the owner of a resource unilateral authority to determine output and set prices for access to the resource in question. In the ordinary case, the monopoly conferred by property is unobjectionable. If there are dozens of farms in a given valley, each farmer has a monopoly over his own farm. But competition among the farmers will constrain the behavior of each farmer-monopolist, such that output and prices will be determined by market forces. Monopolies are troubling only when they confer market power, that is, when they give the monopolist the power to influence market prices through adjustments in output. With market power, the right to exclude confers the right to demand supra-competitive prices and exact other measures that diminish social welfare.

This reasoning leads me to what I think is an obvious question, but one that is rarely asked.

If property rights to locations are little monopolies, but the system generates price competition, why aren’t property titles free?1

After all, the resource cost of granting property rights is zero. Property rights are created simply as database entries listing who holds rights to which locations. Sure, there is a legal apparatus behind the whole shebang, but the marginal cost of creating property rights is near enough to zero.

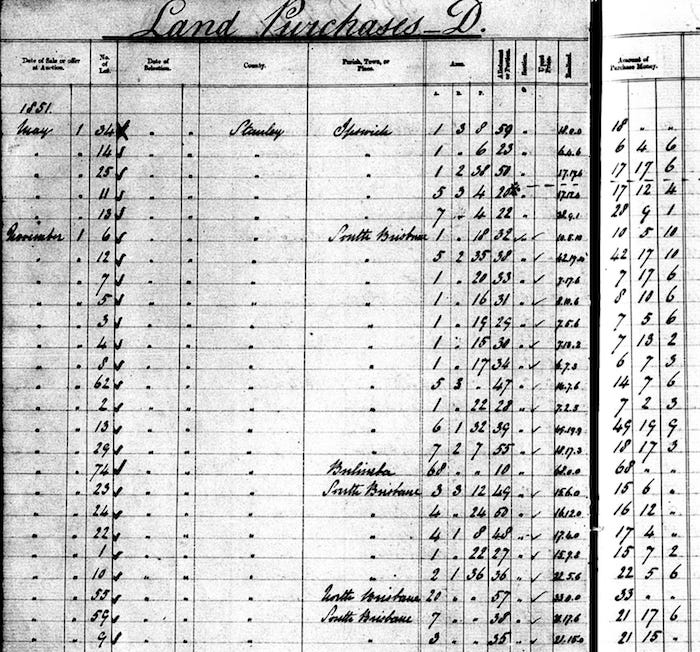

The image below is an example from Queensland, Australia, from the 1850s when private property rights were first established. It shows a series of purchases of land by private citizens from the state government which had simply declared that all the space that already existed was controlled by the state which could allocate property rights however it saw fit. It also records the huge sums paid for these property rights.

Property was created then, as now, by writing a line in a book (database) that we all agree records who holds the rights to which spaces.

The puzzle is this.

If selling off property rights to locations generates competition that brings down prices to reflect the cost of inputs, why were these colonial Queensland land purchases made at a huge positive price?

If the common argument of Glaeser, Merrill, and others, is correct, as soon as all the land is sold from the monopoly state owner to the competitive system of private owners, prices will fall to their competitive level. Each owner, after all, can’t act as a monopolist and generate a price for their land above the cost like the state could.

Since the cost of creating a property ownership database entry is zero, the competitive price should also be zero.

I argue that this doesn’t happen because a system of small monopolies is a monopoly itself—just as the board game Monopoly was invented to show (it was originally called the Landlord's Game). Property markets are never competitive.

Think of this another way.

All the space in a region could be owned by the one monopoly property owner. It is obvious that this will lead to monopoly pricing of all the different locations within that area.

Now imagine that the monopoly property-owning company employs 100 people who each reside in a single dwelling owned by the company. The company owns all 100 dwellings (and only those dwellings) in a region, and all 100 residents of those dwellings are company employees. Each employee owns a 1% stake in the company and their job is to maintain the dwelling they reside in.

Still a monopoly? Surely. A single entity still owns all the property. It doesn’t matter how the ownership of that entity is structured, nor how they manage their employees.

Now imagine that the shareholder-employees of the organisation decide that they would like to change the way they have split up ownership. Instead of owning a 1% stake in the company, they would like to own just their own dwelling—1% of the locations owned. They vote to swap all their 1% stakes in the company for ownership of just the dwelling they live in and wrap up the company structure.

Now what?

If you believe the argument that land markets are price competitive, this should result in a dramatic reduction in dwelling rents. If dwelling asset prices reflect expectations of future price competition, they will immediately collapse.

Which is weird, no?

The only argument that supports this claim rests on the idea of coordination. In the initial situation, where each person owns 1% of all locations, they are able to coordinate with the others because of an overarching organisational structure. In the latter situation, where each person owns 1% of the locations, they now have some kind of incentive to slightly under-price their neighbour at each opportunity, and as that process iterates, prices for access to locations fall.

But this theoretical process never seems to happen in reality.

There are two related reasons for this.

First, monopoly outcomes in a market with no free entry (i.e. where you can’t create a location from a non-location input) are achieved by trial and error with no collusion. The competitive price equilibrium is unstable and there is no way to get there from the monopoly equilibrium.

Second, because property rights are an asset, as soon as one person deviates and starts renting below the market price it becomes attractive for the renter to sublet at the market price and take a margin. If they try to sell below market price there is an arbitrage opportunity for any buyer.

The reality that property is a monopoly and leads to less than efficient investment outcomes has been historically well known. We now also have evidence that when property systems are replicated in online video games the same monopoly behaviours arise. One has to wonder why the opposite argument has become so popular in the past two decades.

This is not the first time I’ve asked this question.

EQUITY Coops like where John Lennon & Yoko Ono in NYC are still affordable.

Very common in 1970 – 1980; LAND is owned by non-profit corporation; UNITS are market with SHARES in LAND. Pre-strata/condo & formal coop legislation. More complex entangled now.

Have not found much Canadian data networks on this. Federal and Provincial funds for retention incentives & new starts do not have these as qualifying property YET.

CMHC plus financial institutions are reluctant to offer mortgages Grants, & Realtors do not understand/ not too keen to take on. WHY?

Isn't the argument of people like Glaeser that by removing restrictions on building tall buildings you can effectively remove land scarcity? Everybody could turn their single home into a block of flats, and/or turn their backyard into a block of flats, and it's really only building costs that would be the limiting factor.

And in such a scenario the number of "property developers" would go from (the well-connected) few to (the non-connected) many, thus avoiding the sort of supply control that currently keeps prices high.