The "zoning tax" is an illusion

A reply to Bryan Caplan's read on the debate

For years I have explained the absurdity of Glaeser and Gyourko’s “zoning tax” method.

I have a short explainer here, and a lengthy academic paper on it here. This is the latest iteration of the debate.

Please first read Bryan Caplan’s piece in the link below about my claim that a popular method for estimating the “zoning tax” is flawed.

It is a thoughtful piece. Let me summarise the key points of agreement and disagreement.

Agreement

The “low value of marginal land might reflect mere “lumpiness.”

Gyourko and Krimmel’s 2021 paper is better.

“I would not expect colonial Australia or ancient Mesopotamia to have big zoning taxes”

Disagreement

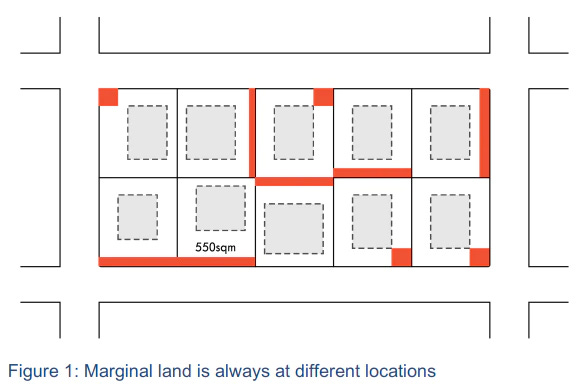

“under laissez-faire, much of the “lumpiness” would probably never have happened in the first place” and “In Murray’s Figure 1, low marginal value of land would have tempted unregulated builders to build 12 or 15 houses”

“Glaeser and Gyourko’s method unambiguously detects the effect of regulation on the cost of individual homes”

“If U.S. real estate values can fall 31% for reasons that remain somewhat mysterious, why couldn’t they fall a similar amount because of massive deregulation? If the point is that sudden housing price falls are dangerous for the financial system, take comfort in the fact that deregulation will come slowly, if it comes at all.”

Why should all lots be priced equally?

The common thread behind our disagreement concerns the plausibility of the assumed counterfactual. In Glaeser and Gyourko’s (G&G) method, the assumption is that absent zoning rules, all property is priced the same on a dollar-per-square-metre basis regardless of size. Indeed, all lots are the same size. All apartments are the same size.

I think this is weird.

No one assumes that all cars are priced at the same dollar-per-kilogram rate as they vary in size. No one assumes that buying one product will be priced the same as buying 1,000 of the same product.

We know unit prices vary with scale.

Why isn’t property the same? What kind of free market would price this way?

A look at laissez-faire

The first specific disagreement is that under laissez-faire conditions “lumpiness” would not occur.

I don’t think this fits the evidence. All cities prior to the invention of zoning had a variety of lot sizes. Some of this reflects the timing of when different parcels were developed and the market conditions at the time. Some of this reflects the shape of the land and the road networks.

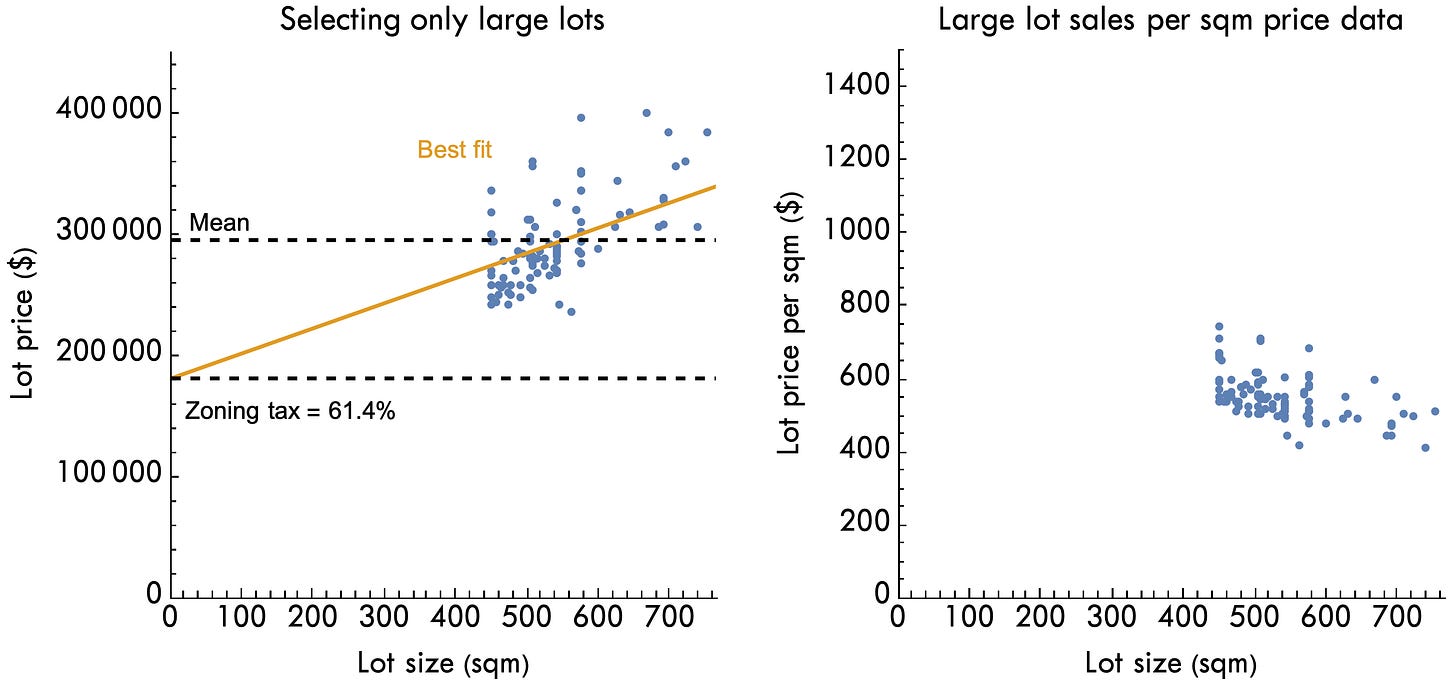

Many new subdivisions see private developers choosing a wide distribution of lot sizes. For example, the below charts show the price of new housing lots in a new major subdivision in Queensland, Australia, with over 20,000 lots approved.

This developer, when given the choice, decided to build a huge variety of lot sizes in their project.

They did this despite knowing that there is a declining marginal price for the area of each lot. For example, they could recombine all the 500sqm lots into two 250sqm lots and make more money.

There seems to be a market incentive to produce a variety of sizes and lot types to meet the demands of a variety of buyers in a timely manner. Free markets usually do that.

This is also an example of where G&G’s zoning tax method finds a massive tax. In this case, G&G’s zoning tax methods would say that 44% of the lot price is a “tax”.

What is basically happening is that a linear model is being applied to a non-linear bid curve. We know that small lots sell for a price premium because a property has location and size attributes, and increasing the lot size, therefore, has relatively small marginal benefits.

It is weird to interpret the intercept of a linear model as containing information about some non-specific planning regulation based on the assumption that all housing lots in a free market would be a) the same price per area regardless of size, and b) all the same size.

In fact, the idea that looking at larger lots overcomes this issue is wrong. Gyourko and Krimmel’s 2021 paper certainly overcomes one critique—that small marginal pieces of land cannot be recombined into one lot. But it still fails conceptually.

I recreate this approach with the same data in the above charts, but this time selecting only the large lots that could have been two or more small lots. I find now that the zoning tax is twice as high!

Why is that? Because there are diminishing returns to lot size. That’s it.

Other disagreements

Developer incentives

It would make sense for developers with most of their net worth already tied up in land to be pro-regulation. The standard business model for developers, however, is to buy land, develop it, then sell out. They make their money by building new stuff, not by sitting on real estate and waiting for it to appreciate. As a result, developers’ support for deregulation is exactly what the mainstream view predicts.On the incentive for developers to want lower prices

This to me is a misreading of what property development is. Property development is not construction. Development is one part of a long asset management process of owning undeveloped property assets then developed property assets. Property owners certainly do make money from owning undeveloped land and waiting.

Property owners (developers) pay construction companies to build. Construction companies make more money by building more homes. But it is not always the case that property owners do.

The biggest anti-planning group in Australia, for example, are developers who own billions worth of undeveloped land and own landbanks that will last them decades. I have a paper on this here.

Indeed, the market itself has a built-in speed limit, known in the business as the absorption rate. Here are a couple of papers of mine on the topic: https://osf.io/xscg5/ and https://osf.io/7n8rj/

Why are we talking about asset prices anyway?

Why are we measuring the price of homes by the asset price of land? Surely rents are the price that reflects the cost of housing in terms of alternative consumption foregone.

In no other asset class do we talk about the marginal cost of supply. Every listed company can issue shares (stocks) for a zero cost and sell them until the price drops down to “marginal cost”. Property is just another asset after all.

Property owners will crash the market

All I can do is point to the evidence.

There are no examples anywhere in the world where removing planning regulations has led to massive reductions in property asset prices.

For example, Auckland Council in 2016 mass upzoned their city and got no change in prices (as in, prices boomed more than 50% since). Minneapolis had a similar experience.

Indeed, if there are big price effects they should be anticipated in the market even from announcements of future upzoning.

Will upzoning resolve the debate?

I agree that many planning systems are cumbersome and gamed by vested interests. But planning regulations aren’t causing high prices.

I have worked for property developers and have a long history with the industry. No one in the industry really thinks they do.

They like to tell the story of planning being to blame because it gets them additional property rights for free and it avoids policies that might actually reduce the value of the assets they own and sell. For example, when under oath at various government inquiries, developers say that prices won’t fall after upzoning and that the market limits the rate of new supply.

My view these days is that I want more cities to copy Auckland by upzoning everywhere. Because the best evidence about what actually happens from changing planning regulations comes from doing it.

I expect that given the new political popularity of mass upzoning that it could become a more common policy change.

However, if the same people who blamed zoning for high prices start finding other regulations to blame because the price outcome wasn’t what they thought, you will appreciate that I will no longer take any of their arguments seriously.

But if announcing upzoning across America tomorrow crashes the housing market, as implied by the idea that there is a huge zoning tax that can vanish with the stroke of a pen, I will concede that I was totally wrong.

For interest, I'll post part of a comment I also posted on Bryan Caplan's blog piece.

One of your points (Caplan lists it as #1) is that high land values might reflect good planning, but G+G have assumed high land values are a symptom of bad planning. They've assumed the conclusion.

The problem with G+G's assumption can be illustrated with a thought experiment.

Suppose some jurisdiction always got their planning rules just right. Suppose the rules changed through time but were totally optimal at each point in time. They were the best set of rules imaginable, always. The rules let lots of people live there and made living there GREAT.

Would people pay a lot to live there or not much at all?

They would pay a lot. Land prices would be high.

Suppose also that buildings lasted quite a while and technologies and preferences changed a bit over time.

Might there be a few over-sized backyards which were privately optimal at the time they were created, but wouldn't be created if the land was vacant today? Of course.

So with the best of all planning rules, land would be expensive, and marginal and average land prices would not be equal.

I can see G+G's argument that marginal and average prices WOULD be equal if houses were continually torn down and rebuilt. But in the real world that destroys valuable capital, so it isn't privately profitable to do it even if the rules allow it.

In the real world, cities have a history, and good planning makes it good to live somewhere which makes land expensive.

One further thought experiment can illustrate this point.

Suppose a jurisdiction was previously "naughty", and now they have average prices exceeding marginal prices.

However now they saw the light and liberalised their planning policies. Now it's laissez-faire.

What is the equilibrating mechanism that would drive average prices down to marginal prices?

Would bits of low value land move? Impossible.

Would houses be torn down and shuffled over a bit? Maybe.

But tearing down houses destroys capital. Lots of houses add value to the land they're on. You lose that when you tear them down. So that won't happen immediately. Which means a marginal vs average differential will remain for a long time.

Can you point to a good summary of the Auckland and Minneapolis upzonings?