You can't buy a home young if you aren't working young

We are buying homes older because we are doing everything older

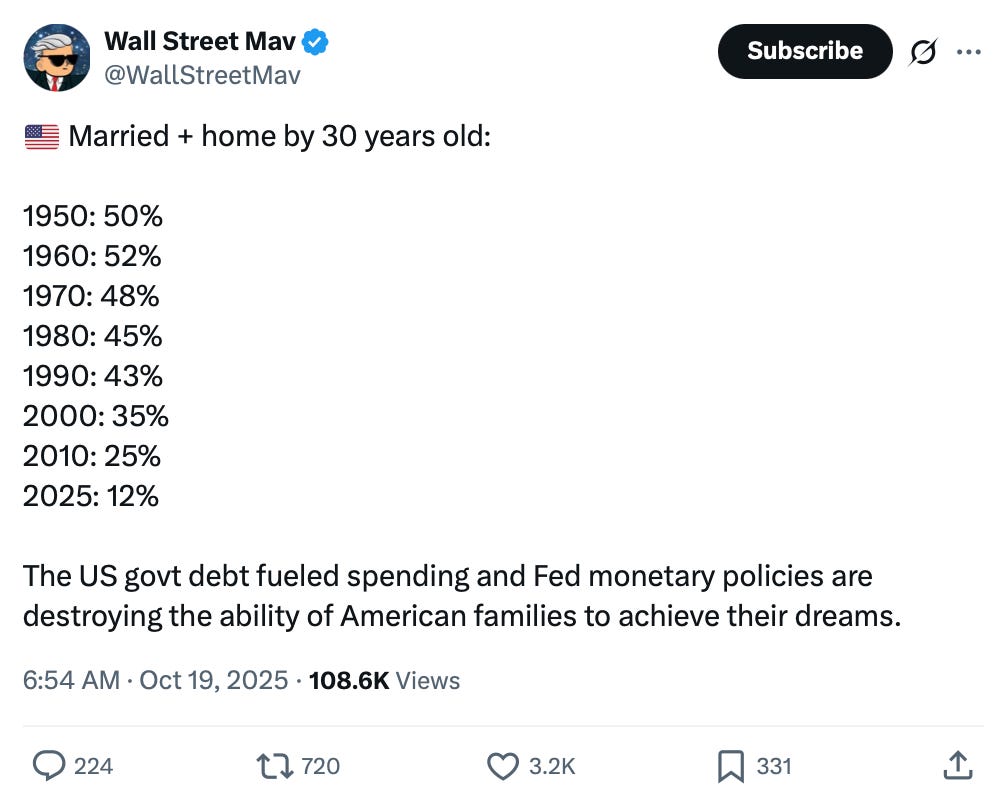

You will often see data like in the tweet below about the declining rate of achieving life milestones by age 30. In this case, being both married and a homeowner by age 30 has declined from 52% to 12% in the United States since the 1960s.

I’m not going to dig into whether the data is correct, though that is my normal first reaction. If I had to bet on it, I’d say the data is wrong. After all, we know that it’s the charts that lie that go viral, and that other data showing a surge in the age of first home buying in the United States is wrong. A brief look at some alternative data (fourth chart at link) suggests this is probably exaggerated.

But let’s park that.

Instead, today I want to reiterate that all life milestones are happening later in general compared with the post-war period. Our lives are now stretched out. This pattern was explored in detail in this post (for paid FET subscribers).

Get access to all paid articles, audiobooks, and charts by becoming a paid FET supporter and keep Australia’s newest one-man think-tank in business. If you like what you read, please also use the share button to be rewarded with a subscription if you refer new FET subscribers.

Thank you all!

Here, I want to make one important point about our stretched-out lives that helps us sensibly interpret long-term trends in age-related milestone data: marriage and homebuying milestones are happening later in life because we have squeezed in extra life milestones to achieve beforehand.

One big new milestone is education.

More people, especially women, are studying.1 And we are studying longer, both at high school and at university.

This means people in general start work later in life, and you can’t buy a house young if you aren’t also starting work young!

The chart below shows that in 1980, half the Australian men aged 15-19 were working full-time. This is a similar rate to men aged 20-24 in the 2020s.

Yet back in 1980, nearly 80% of men aged 20-24 were working full-time. Now? It is down to 50%.

Women in both these younger age cohorts are also working less.

That’s because so many young people are at school or university nowadays.

After the age of 25, women are working more. Why? I don’t know. Perhaps getting a return on that education investment and having children later or not at all. Perhaps the rise of childcare use is a factor, too. Understanding this is a task for another day.

Below is the data on the average age of first homebuyers in Australia.

According to the HILDA survey, which asks people of all ages how old they were when they first bought a home (and hence allows us to cast back some estimates a bit longer than the ABS surveys), the average homebuying age in 1980 was about 27 years old. In the 2020s, I would estimate it has been flat at age 32 (assuming it has been quite flat since the 2010s due to the big spike in first home buying since 2017).

If you take the ABS data, you see a three-year age jump since the mid-1990s.

Overall, a sensible conclusion from this imperfect data is that the average age of first home buying has increased by about five years since 1980.

This is roughly the same increase in age that has occurred for beginning full-time work as well. If the average age starting full-time work used to be 19 years old for men, and now it is 24 years old, then people in the 2020s are working the same seven years before buying a home that they did 45 years ago.

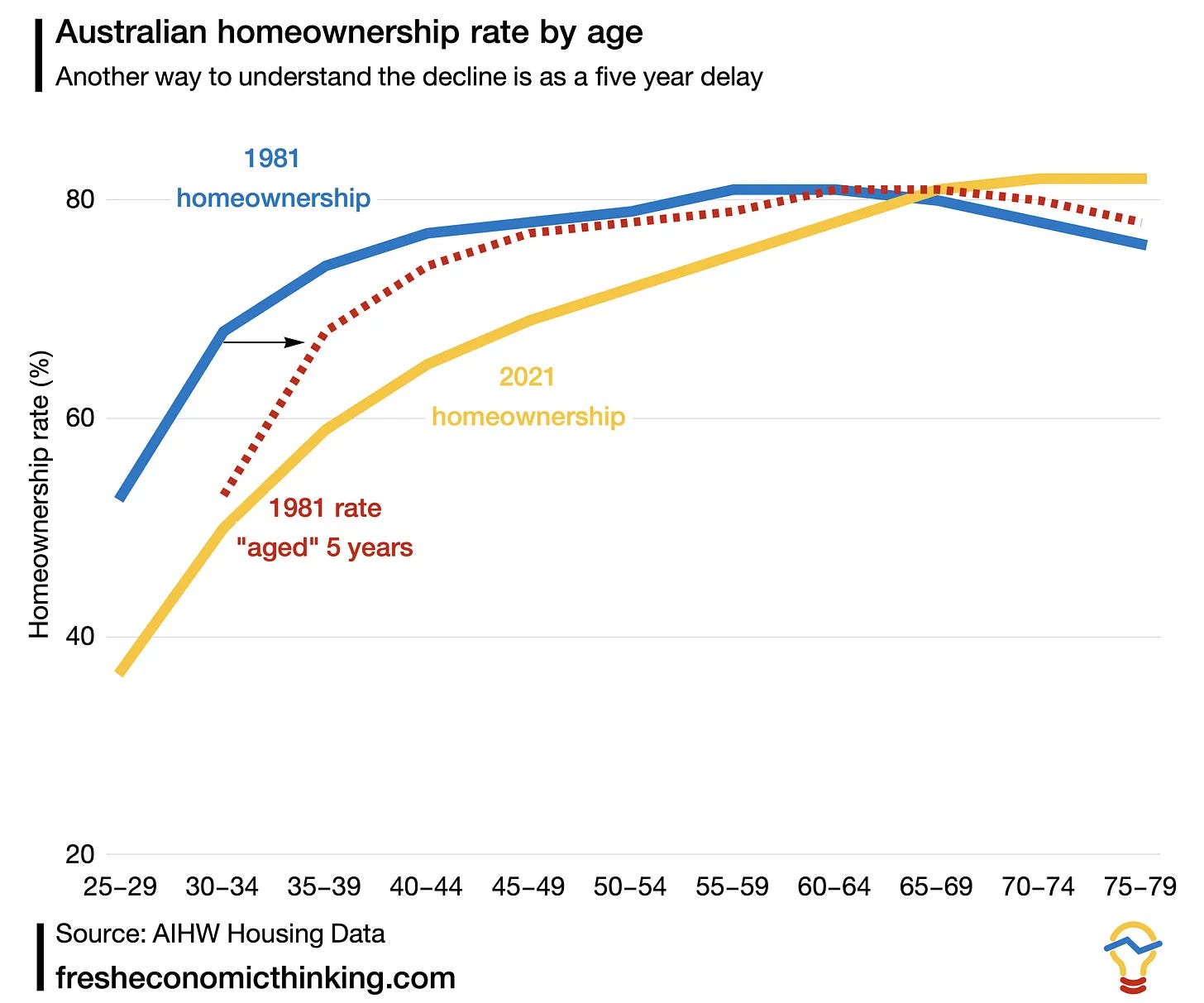

If we plot homeownership rates by age, people often see the line going down. In the chart below, the yellow line, which is homeownership rates by age in 2021, looks to be below the blue line, which is homeownership rates by age in 1981.

But much of this decline in the young age groups is not a fall, but a rightward shift of five years due to our stretched-out lives and the extra five years of study.

I show what the 1981 data “aged” five years looks like with the red dashed line. It gets much closer to the 2021 data for young households (those aged 34 and below). Education possibly explains some of the later homebuying delay due to status factors (e.g. thoughts like “we both have university degrees and expect our incomes to rise soon, so let’s wait and buy in a better location”). But education alone doesn’t explain the whole change across the age distribution over the past four decades.

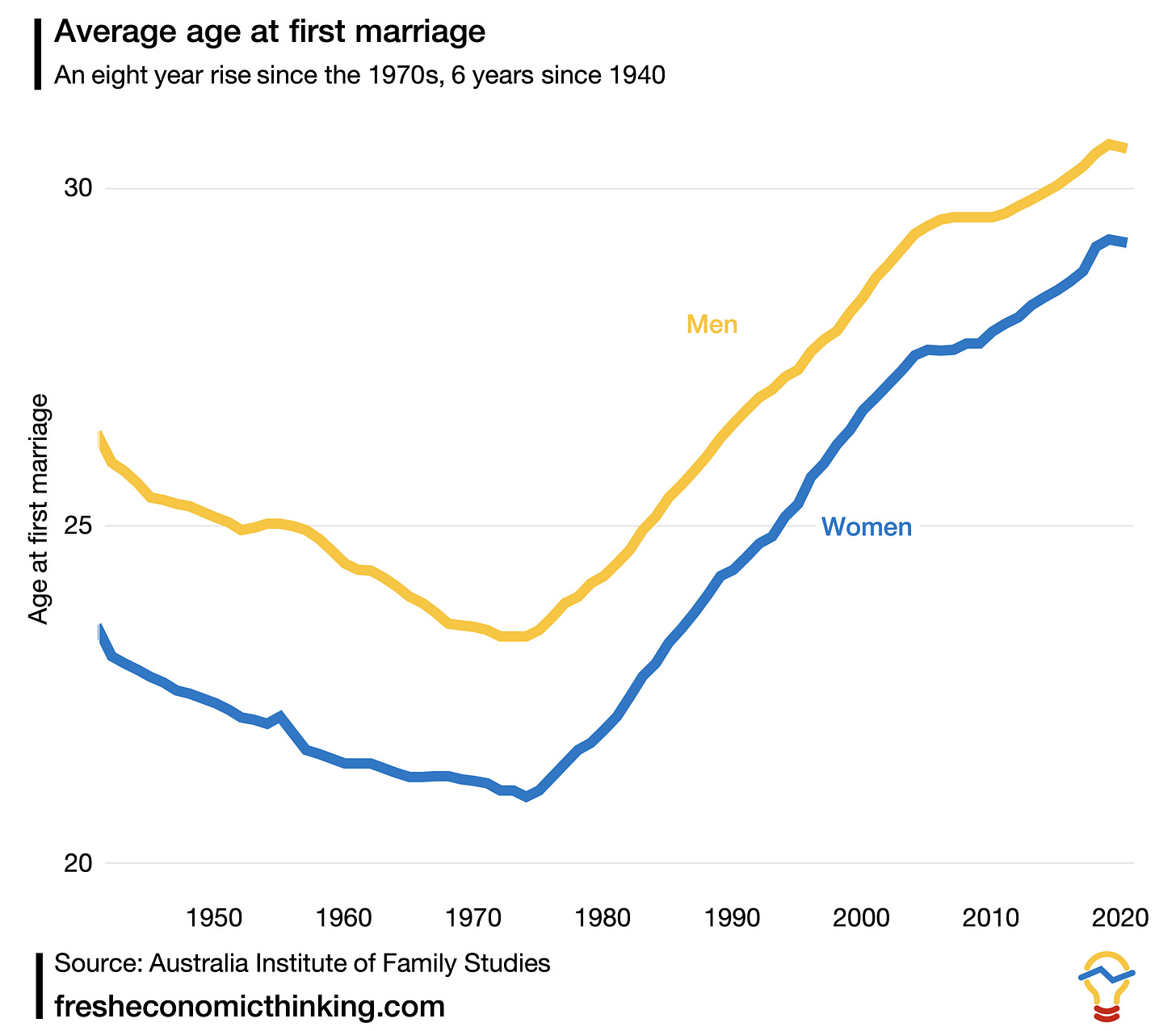

Marriage is later, too, as you can see below.

If dual incomes are important for saving and homebuying, as they clearly were in the past with such high rates of full-time work for women aged 15-24, this adds another piece to the economic story.

What we see then is on average, in 1980, by age 30, couples had worked a combined 17 years full-time and been married for eight years, on average (and many wives had stopped working full-time by this age to care for children).

In 2020, by age 30, couples on average have worked a combined 12 years full-time and been married for one year.

Nothing is physically stopping young people in the 2020s from studying less, working more, marrying earlier, and buying homes earlier. Maybe some of these trends will reverse in the coming decades.

But our stretched-out lives combine to generate later milestones like marriage and homeownership, and we need to understand the broader social and economic context if we want to sensibly interpret these patterns.

As always, please like, share, comment, and subscribe. Thanks for your support. You can find Fresh Economic Thinking on YouTube, Spotify, and Apple Podcasts.

Interested in learning more? Fresh Economic Thinking runs in-person and online workshops to help your organisation dig into the economic issues you face and learn powerful insights.

It might surprise many readers that since 1987, the majority of university students in Australia have been women! Not only is overall participation in university among 19-year-olds rising, from below 15% in 1980 to around 50% in 2020, but this is mostly due to rising female university students. The chart below is from James Nuzzo, who was on the FET podcast last week.

Listen to that podcast here:

This tracks with my observations, but that chart is stupid.

One factor that I think drives men but particularly women's participation in higher education is the credentialling of female dominated industries. Being a teacher never used to require a 3 or 4 year degree and a Bachelors. My mother-in-law got her diploma of teaching 2 years after high school and was in a classroom for 6 months of that two years. She cut her teeth teaching in Bondi Public school before Bondi was gentrified, it was a lesson in the best and worst of humanity. Nursing was basically an apprenticeship until the 1970s as well. So was engineering, business administration, childcare, accounting, journalism, radio and television broadcasting etc... cadetships, apprenticeships and professional development have all been outsourced to universities which I think has reduced the need for 'entry level' jobs to be provided because workplaces use degrees as a heuristic for quality control in these professions. Now its coming back to bite us because we've pushed a ton more kids into academic environments that aren't suited to academics, or simply can't afford the opportunity cost of part-time work for 3 years. Many would be wonderful nurses, teachers, journalists, engineers etc if they had access to apprenticeship/cadetship models of education in these fields where quality is really dependent on actual hands-on experience and could earn a decent wage for real world work.

You now need a three year degree to fill out paperwork and break wind in an office these days and we deny teenagers VALUABLE life experience by insisting that they must get into Uni at all costs so don't get that job stacking shelves at woollies or at the bakery or a lifeguard at the pool over summer, it will distract you from studying.

It seems that just about all categories of people are 'starting life out later' as a reflection of population ageing - increasing retirement ages, increasing amount of time spent studying, and careers starting out later.

One of the difficulties in trying to make an 'apples-to-apples' comparison between demographics and generations is that consumption spending was relatively more expensive as a share of income for young boomers, for example. There were also fewer available consumption opportunities. So high asset prices are arguably a reflection of 'cheap consumption.'

I think that if one was to take a typical 1970s consumption basket and rely on it for their living today, they would have considerably more income leftover to service housing costs. It would, however, probably not be a particularly adequate standard of living by today's standard.

We often associate the period of decades ago with 'better value' for money in terms of price levels being much lower than they are today. What matters, however, is the level of those prices relative to the incomes. For many goods and services, the relative prices today are much cheaper than they were decades ago.