The Auckland upzoning myth: Response to comments

We identified three major flaws in a landmark paper about the construction effects of upzoning. No-one disagreed with these flaws. Now we respond to three new questions.

A widely cited paper in the zoning and housing supply debate is The impact of upzoning on housing construction in Auckland by Ryan Greenaway-McGrevy and Peter Phillips (GMP), published in the Journal of Urban Economics (free version here).

It’s a popular reference for claims that city-wide upzoning boosts new housing supply.

Our last post in June laid out three major methodological flaws with this paper. There has been no disagreement with these three main points.

This post addresses responses from our readers to that post, explains in even simpler terms how GMP’s estimates were derived, and provides a spreadsheet replicating the results, so you can see this for yourself.

We didn’t claim to prove that upzoning had no effect on new construction. We claimed that GMP failed to use methods capable of identifying one.

No disagreement on the major flaws

No one disputed our three core points.

1. Biased sample

Did you see the AFR chart showing a clear uptick in upzoned areas? It’s an artefact of using a biased data sample. There was no structural break in total consents in the full sample.

No one disputed this.

The only question was whether Ryan Greenaway-McGrevy’s May 2023 extension paper, which applied the same method as in the published paper to the full data sample, had adequately addressed the problem. We deal with that below.

2. A linear counterfactual in cyclical data

Ever climbed Rangitoto? It’s a steady gradient – until it’s not. There was no disagreement with our claim that applying a straight-line assumption to forecasting future growth in a cyclical data series is a practice fraught with danger.

The paper relies on an unrealistic counterfactual in which a linear assumption implies that the growth in building consents would fall to half the pre-upzoning rate.

3. Consents are not new homes

The paper didn’t do what it said on the tin: it measured building consents (approvals) rather than dwelling construction.

Stockpiling pieces of paper with approval to build (consents) does not grow the stock, nor does replacing one building with another.

Net additions, as you can see below, have diverged from consents. No one disputed that the point under debate was the effect of zoning on approvals/consents, not on construction or net additions.

Readers’ responses

The responses to our post boiled down to three key questions:

Is that really the counterfactual? Surely not.

Doesn’t the extension paper resolve this?

If upzoning didn’t change supply, why did rents fall?

Let’s take each in turn.

1. Is that really the counterfactual?

A friend of ours reckons that only science fiction writers and economists are truly happy working with ‘counterfactuals’.

Was the counterfactual GMP used to estimate growth in consents due to upzoning realistic? Here’s a test for you.

It’s the end of 2015.

Building is booming. Consents have grown by 12% per annum since their post-GFC low to hit 9,000 per annum in 2015 (still a few thousand short of the pre-GFC high). And after a decade of zero net migration, immigration has kicked up rapidly. NZ’s population is now growing 40% faster than Australia’s in relative terms.

After a marathon debate, the proposed Auckland Unitary Plan (AUP) is rejected. Upzoning advocates hoped to see zoned capacity for new dwellings triple from 300,000 to 900,000. Instead, they are disappointed. Zoning rules stay as they are.

If you lived in 2015 in this alternative no-AUP world, which path would you bet on in the image below for dwelling consents?

Would you have picked D?

We wouldn’t have either. But D is the counterfactual used by GMP to conclude that anything above this is the effect of the AUP on new dwelling consents.

Readers expressed disbelief at this.

It’s hard to see it in the paper as the details are buried within the econometrics. We explained it in a simple, transparent way so that you can be the judge.

Are we sure? Yes. We read this paper cover to cover and replicated the method to successfully reproduce the results. Then we checked our understanding and replication with the authors.

GMP effectively assume that, without the AUP upzoning, growth in consents would suddenly have slowed down. Over the five years prior to the AUP, annual growth in consents in GMP’s sample averaged 12.1%. But GMP’s counterfactual for the six years following involves an average annual growth of just 5.7%. So it’s no surprise they found upzoning doubled growth.

Whether the authors appreciated this fact, or lost their intuition amid the econometrics, is beside the point.

You can now replicate GMP’s results yourself. We’ve provided a spreadsheet to do just that. It uses just nine data points and three columns to replicate the paper’s main results of 22,000 extra consents from upzoning.1

This is our simplest explanation of the method.

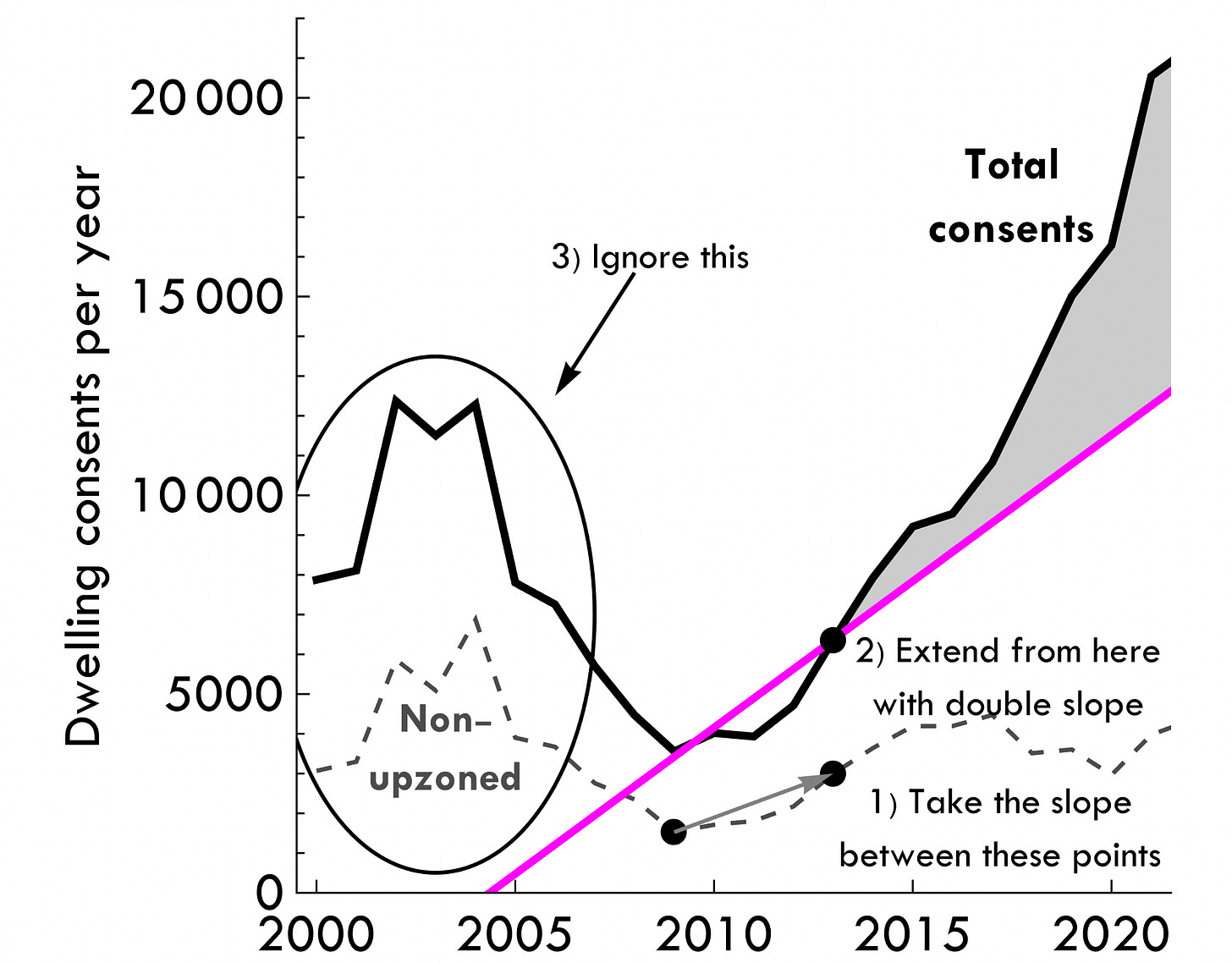

Take the 2015 non-upzoned data point, subtract the 2010 point, and divide by 5. That gives you the slope used to generate a counterfactual.

Begin from the 2015 total. Add twice the slope previously calculated (once for each of the two groups the total is partitioned into) and add that to the 2015 total to get a counterfactual 2016 figure. Then add twice the slope again for each year until 2021.

Subtract the actual total consents for 2016 to 2021 from those counterfactuals.

As you can see from the charts in the spreadsheet, this looks reasonable with the sample data, but quite odd when applied to the city-wide total data, as in the chart below.

The problem is that all locations and consent types are substitutes, and by removing certain data, GMP are simply tracking location substitution and misidentifying it as a net change in total consents.

What might have been better?

Comparison with other cities, for one. Or something like the “eyeball counterfactual” below. We’re not claiming this is the “right” counterfactual. But this is what similar data series look like in cities that didn’t have zoning changes.

2. Doesn’t the extension paper resolve this?

In short, no.

One of the authors released an Update and Extended Results paper in May 2023. It expands the sample to include data missing from the published paper, brings forward the starting point of the upzoning, and adds data for 2022.

Unfortunately, it applies the same flawed counterfactual construction.

This time, instead of extrapolating a five-year straight-line trend for six years from the date of the AUP, it extrapolates a four-year trend for nine years from the date when an earlier upzoning policy began.

Here is the extension paper result, annotated to show the method. Please apply the same test as above. Is the pink line a realistic counterfactual for the black line?

The extension paper fixes one problem by making another problem worse. It fixes the biased data sample but worsens the problem of using linear extrapolation on a clearly non-linear series. The counterfactual literally extends a straight line from the 2009 minimum, to a point four years ahead in 2013, on this clearly cyclical data.

Using this method, any deviation of total consents from a straight line fitted to a few years prior to the upzoning will be attributed to the upzoning. Had immigration stalled or markets crashed in 2016, this approach would be telling us that the AUP had reduced construction!

3. If upzoning didn’t change supply, why did rents fall?

This one is straightforward. Rents changed in accordance with population, income, preferences, and housing stock.

The stock of homes did increase quickly during the building boom. That’s plain in the data. But it’s the attribution of this to upzoning rather than to ordinary construction cycles we’re contesting. There’s plenty of evidence that while zoning effectively regulates locations and housing types, it is market forces that regulate the overall rate of new dwelling construction.

Rents subsided in Sydney for many years after a large construction cycle in the 2010s too. Maybe, as in Sydney, Auckland rents will rise again soon. When consents fall away and rents rise, will upzoning get the blame?

We don’t know how many extra dwellings the AUP is responsible for. We don’t think anyone else does either.

But the story that upzoning produced a huge building boom is becoming an urban myth.

Cherry-picking figures, uncritically citing a paper with known methodological issues, and writing fairy tales about a small and plucky city far away is well and good when pushing a policy agenda.

YIMBY blogger Matt Yglesias is frank (and tongue-in-cheek) at times about the role these tales serve:

Like all self-respecting Americans, I mostly care about foreign politics in order to shadow box about American issues.

But if that’s your game with Auckland and upzoning, please be honest enough to admit you’re playing politics, not doing economic science.

The rest of the paper just establishes the statistical significance of treatment versus counterfactual control.

Thanks for diving into this further! When looking at the graphs, here and the papers, it does seem like something changed. When thinking in cycles, I do not think anyone would have expected the rise would have continued that long. Naturally the disruption can be caused by many other things, like pandemic after shocks, so it's indeed poor evidence for the effect of the policy, but not implausible and I do not buy it as evidence it is a 'myth'. I buy your point it likely mostly changed location of the builds, but that is still half a win, as it likely means people live closer to where they want to live.

My question is not about the work, itself. It's whether the media that jumped to embrace the initial study are likely to similarly publicize its debunking.

We've been having similar debates in California, but the media pay little attention to the growing evidence that zoning issues do not determine the amount or cost of housing produced.