Removing stamp duty is now claimed to miraculously boost homeownership

A new paper finds that removing stamp duty could boost homeownership, ignoring the New Zealand experience where the opposite occurred.

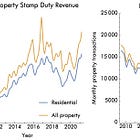

Stamp duty is a state tax on property transactions levied at a few per cent of the value of the trade, with higher rates applying to higher-value trades.

One of the most popular tax reforms in Australia is to remove stamp duty and enact a broader land value tax, which is an annual tax levied on the assessed land value for each property, traded or not. It is usually applied at a rate of 1-2% of the land value.

Many miracles are meant to arise from this tax swap – from more household relocations to cheaper housing and greater economic efficiency.

But these claims are mostly based on hope, not evidence. I’ve debunked the main claims in these two articles.

The latest miracle claimed to arise from removing stamp duty is that it will increase homeownership.

A new paper in the Economic Record got some press coverage for its claims about how much removing stamp duty could increase homeownership. The economic and political tribes fell predictably into line behind it on social media.

The main result of the paper was as follows.

The NSW Government's 2020 proposal to replace stamp duty on all properties with an annual tax based on unimproved land values is estimated to increase home ownership by 6.6%, through changes in purchaser holding periods, a shift of tax burden from investors to owner-occupiers and a relaxed deposit constraint.

In terms of homeownership rates:

Overall, the modelling suggests home ownership could increase in the long run from 67.1 per cent of the private dwelling stock to 71.5 per cent, which is a 6.6 per cent increase.

How is the New Zealand miracle going?

In 1988, New Zealand removed stamp duties from residential property trades, and in 1999 removed them from all property trades.

The outcome is that homeownership there is now the lowest it’s been in 70 years.

The chart below from Stats NZ shows a fall in the homeownership rate from 73.8% in 1991 to 64.5% today, which is a much bigger drop than Australia has seen in recent decades with its cumbersome stamp duties.

A miracle in the model

The new paper is based on a modelling exercise that assumes that increasing turnover will lead to a higher proportion of first-home buyers.

It’s not a bad paper. It shows the sensitivity of the results to various assumptions, the critical ones being how much extra turnover comes from investors or homeowners selling (which are inputs to the model, not outputs).

But I think there are some strange assumptions.

For example, in a pure homeownership market with no investor buyers and no change in the stock of housing or number of households, changing the frequency of trades would not change the homeownership rate; it will always be 100%.

If stamp duty reduces the cost of trading, there will be more trading. But every seller is also a buyer, even at higher levels of turnover. If there are five sellers, that means there are exactly five buyers. If there are ten sellers, there are exactly ten buyers as well.

Changing the frequency of trade doesn’t change this fundamental relationship. Only if investors sell relatively more can higher turnover lead to higher homeownership. As we can see in the image above, this is exactly the assumption that generates the result of higher turnover leading to higher homeownership.

The forgotten forced renter moves

It is also weird to me that stamp duty is now often relabelled as a moving tax.

But stamp duty also taxes housing trades between investors, which usually force renter households to move when they don’t want to.

Stamp duty taxes turnover, which is not the same thing as mobility.

New Zealand has a housing turnover rate of about 7-9% per year, while Australia has a rate of about 4-6%. A sizable difference, most likely due to the low transaction costs there.

But that also means that renters in New Zealand are much more likely to be forced to move because of a home sale.

In Australia, surveys suggest that about 14% of renter moves are because a lease was not renewed for any reason. But in New Zealand, a survey of over 1,000 tenants in 2016 found that 30% of renter moves were because the landlords sold the house, with this being the reason behind 36% of renter moves in Auckland.

New Zealand Treasury has noted the gains to renters from fewer property transactions.

In Auckland, reducing the turnover of rental properties is likely desirable to increase tenants’ stability of tenure. As noted above, Auckland’s short-term housing market turnover is high, with houses with highest levels of short term turnover concentrated in areas with relatively large investor participation.

Reducing the cost of transacting by removing stamp duty is likely to have a much larger effect on the rate of transactions of landlords compared to homeowners.

We know that people don’t buy expensive houses with the expectation of frequently selling and moving. Households choose to rent instead if they don’t plan to stay in one place. Sure, they do this partly because of stamp duty, but these behavioural responses also decrease the effect of stamp duty on reducing mobility.

In fact, 30% of renters in the ABS housing mobility survey say that the costs associated with moving are why they wouldn’t move, but only 21% of owners say costs are a barrier to moving.

Less frequent trades improve stability

I ran two Twitter polls. One about whether adding costs to trading assets results in less or more concentrated ownership and one about removing costs.

Most people thought that both adding and removing costs to asset trading increased concentration of ownership.

Essentially, we all think any change is bad.

Let’s bring these threads together.

A new study reckons that removing stamp duty will increase homeownership by an astonishing 6%, reversing a half-century of decline. This seems a bold claim since the best real-life case study is New Zealand, and their homeownership declined after stamp duty was removed.

It turns out, that the bold claim is based on the assumption that higher turnover means more investors selling and fewer homebuyers selling. The study assumed its result.

Indeed, lower turnover is generally good for renters. More investors selling means more forced and unnecessary renter moves, which is a big problem in New Zealand.

And when we ask people whether higher costs of trading means higher concentration of ownership (i.e. more investor owners owning more homes each, rather than broader homeownership) people have no idea.

Thanks for diving into the stamp duty paper.

I can imagine that if the stamp duty to LVT switch increased the tax concessions for owner-occupiers relative to investors, then the composition of the seller and buyer cohorts would change in a way that produced the result. But then the result wouldn't be due to the removal of the transaction tax per se. We could keep stamp duty but make it punitive for investors and it would achieve the same thing.

From your reading, however, that's not why the result occurred. The result was by assumption. Interesting!

I have reached out to the author to ask him to upload a non-paywalled version.

It becomes increasingly obvious from Cam's arguments with property tax reform that specially targeted tax design makes more sense for achieving specific objectives rather than wholesale broad based tax changes for the sake of neutral tax treatment and "efficiency". Especially given the high political (and/or fiscal) cost of making these tax changes.

Do we want more new dwellings? Then tax new dwellings less.

Do we want more homeowners? Then tax people who don't own a home less. Tax people who own more than 1 property more.

Do we want wealthy people to stop banking wealth in their PPR as a tax shelter and keeping potentially good development sites off the market? Then tax those properties more.

Do we want pensioners to not face barriers to downsizing due to asset testing? Then create tenure neutrality for asset testing the pension.

Maybe if we actually started talking about making small tweaks that moved in these directions and made it a long term objective, we would start getting somewhere.