Retirement Rort: The economic case against Australia’s superannuation orthodoxy

Everyone who studies the superannuation system closely learns its flaws. Here's why it is time to move on from "super is good, let's improve it" to "super is fundamentally flawed, let's scrap it"

Our perception of the problem of poverty in Australia is flawed.

We don’t have an old-age poverty problem. We solved that with the age pension.

We don’t have an unaffordable age pension problem. We solved that via the tax system.

The logic behind Australia’s tax-advantaged compulsory-savings superannuation scheme rests on this flawed perception. This means that superannuation, as a system for providing retirement incomes and preventing old-age poverty, is also fundamentally flawed.

It is not fundamentally good but poorly implemented. It is fundamentally flawed.

As a background, downloadable below is a 2020 report I wrote outlining some major problems with superannuation. This is where I first publicly said that having a superannuation system is worse for most people over their lifetime than not having it, and hence we should scrap the system to make more Australians better off.

To unwind the system, current superannuation payments could be required to be deposited into a worker’s regular bank account so they can spend or save as they choose. From existing super balances, a maximum withdrawal of, say, $15,000 per year can be allowed over a transition period of five years, then after that, all remaining super funds will retain their asset portfolios and be converted into non-tax-advantaged investment funds.

Please note that my anti-superannuation stance is not based on emotion.

Initially, my emotions led me to feel that superannuation must be good because it tickled my sacrifice impulse. Saving feels good. Super requires saving. Therefore, super is good.

It took a lot of hard logic to overcome that impulse and accept that superannuation as a system does the opposite of what we think it does, and it was misconceived from the start.

Superannuation makes economic life worse, not better, for these reasons.

Super doesn’t de-risk ageing. There is no risk-pooling. What you save is what you get.

Super doesn’t smooth lifetime incomes. It isn’t something extra above your counterfactual wage income. Superannuation simply makes you poorer when you are young and poor and richer when you are old and rich.

Super soaks up a huge amount of economic resources. Much of Australia’s top talent is diverted into this unnecessary industry. It also games the rules at the margins to cost us extra billions (like unpaid super, insurance, bundling advice, incurring duplicated fees from multiple accounts, etc)

Super reduces overall investment incentives in the economy. It does this by reducing household spending and hence reducing demand, the opposite of what we need for growth to support more non-workers in the population.

Super encourages early retirement and less labour force participation. Because you can withdraw super only if you stop working at age 60, there is a huge incentive to do so. This increases the non-working population in that age group.

Let’s address each in turn.

Scrapping superannuation is not far-fetched. Other far-fetched ideas of mine have become policy platforms.

When I wrote Game of Mates (now republished as Rigged) I explained how town planning rules are used to provide billions in windfall gains to favoured property owners and that this value should be priced. No one was talking about this at the time, but since then, Victoria has adopted their Windfall Gains Tax to do just that.

In The Great Housing Hijack, I argued that if the housing market is delivering outcomes that don’t work for everyone, we can improve outcomes by creating more non-market housing options with a major public housing developer. This is now the platform of the Greens (with Labor considering) and is also part of Canadian policy debates.

Interested in learning more? Fresh Economic Thinking runs in-person and online workshops to help your organisation dig into the economic issues you face and learn powerful insights.

For some more background on retirement systems, I have removed the paywall on this FET article from last year about the idea of PENSION BONDS. Check it out.

1. Super doesn’t de-risk ageing

Because superannuation comes only from your own personal income, it doesn’t insure you against many of the negative outcomes that often generate poverty in retirement.

If you become disabled during your working life, but live to old age, superannuation doesn’t help you. You will likely rely on a disability pension and then the age pension.

Insurance that de-risks ageing requires pooling risk with others who will work and contribute to the system, but themselves don’t use the system.

The age pension does this.

We all contribute premiums in the form of taxes, which scale by income and wealth. Those who live a long time with no other retirement income source get a payout, while those who earn too much, have too much wealth, or die before retirement age, pay their premiums but never get a payout. For reference, about 17% of males die before age pension age 65.

Just like we don’t need a special savings account to pay for car repairs when we have car insurance, we don’t need a special account to pay for retirement income when we have retirement income insurance in the form of the age pension.

Sure, you can argue about the size of pension payments, the tax concessions to pensioners, the qualifying age, or other such things. But the system really does work to insure against old age poverty.1

This lack of insurance function in the superannuation system is why analysts at Grattan have recently proposed that superannuation funds offer fixed-income products that last the lifetime of the fund holder so that they don’t “outlive” their savings. The Treasury is also considering such issues.

Super is not de-risking ageing, even though many assume it does.

The age pension system does a good job of keeping people out of poverty in old age—so much so that age pensioner households report some of the least financial stress out of all households.

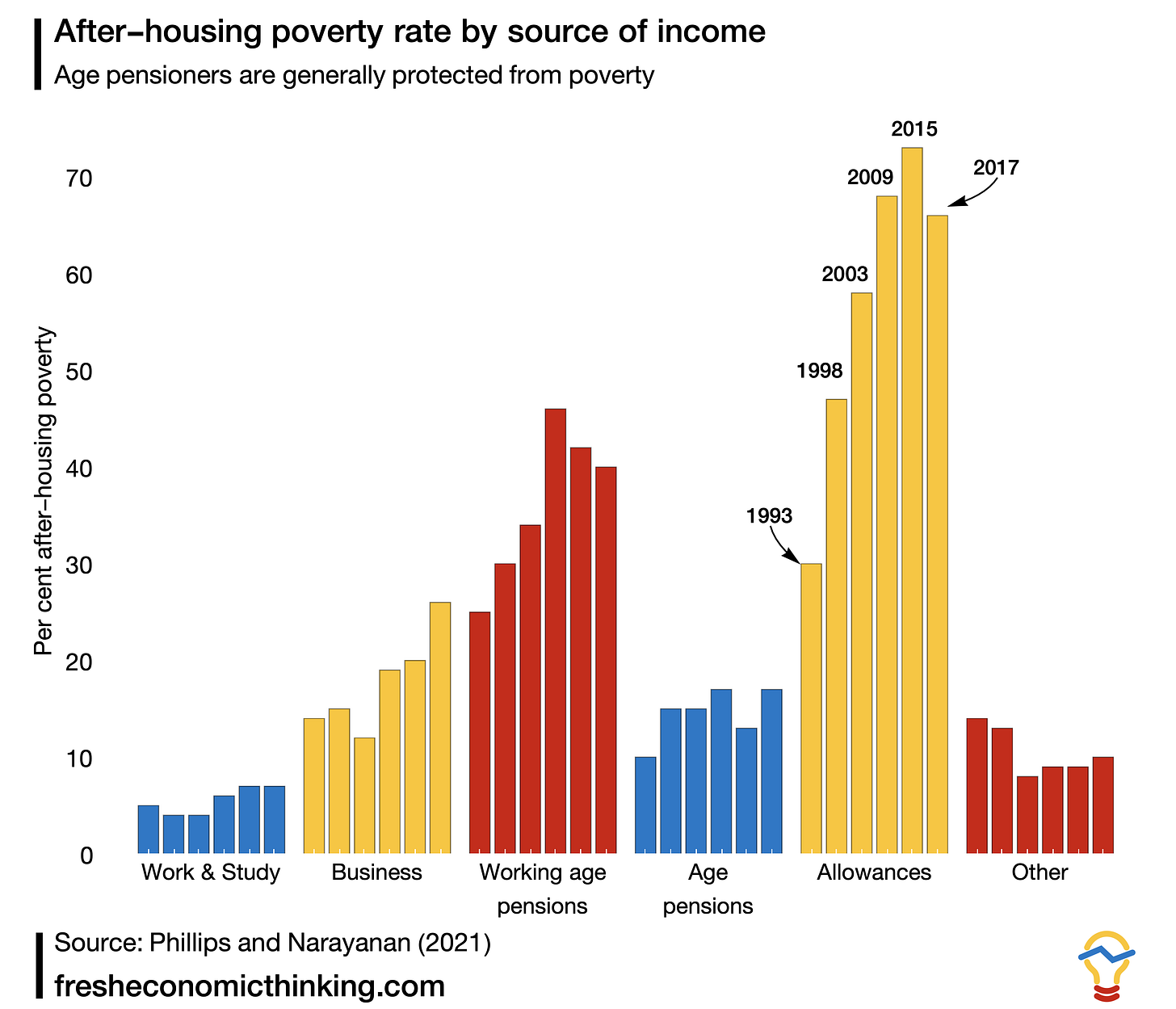

For example, the data plotted below shows the share of each household type, sorted by a household’s main source of income, roughly every five years from 1993 to 2017. Age pensioner households have low poverty relative to many other households, especially those relying on working age pensions, such as disability pensions and welfare allowances. It is working-age households, especially renters relying on welfare in some form, who face much higher poverty than age pensioners.2

2. Super doesn’t smooth lifetime incomes

There is a powerful idea that superannuation smooths lifetime incomes—it makes you richer when you would otherwise be old and poor, and poorer when you would otherwise be young and rich.

Sounds a bit strange when put that way, right? Where are all these young and rich people?3

Let’s unpick this flawed part of superannuation mythology.

Generally, even without superannuation, people are richer when they are older compared to when they are younger. However, despite this obvious reality, an informal superannuation policy objective is to ensure that people in retirement don’t see their incomes fall by more than 30% from their pre-retirement level.

We call this the income replacement rate (a person’s retirement income relative to their immediate pre-retirement income).

I don’t know why this is important.

If I make twice the average full-time salary in the years before my retirement, I can probably make do with less than the full-time salary after retirement. If I don’t think I can, I can voluntarily save more then, as many do. After all, the 50s are typically people’s peak earning decade.

Treasury says that:

Replacement rates align with the objective of achieving a reasonable balance between living standards in working life and retirement. The suggested benchmark replacement rate is 65-75 per cent.

Why benchmark to the highest income years in your life rather than the income in your 20s, 30s and 40s, when you were paying into your superannuation and when you likely lived in a home supporting others financially?

A 70% replacement rate means that your disposable income in retirement is likely higher than it was for most of your working life.

When you further adjust for the cost of raising a family and renting or paying a mortgage, the per-person household income in your 50s is usually extremely high, and even 70% of that will be far more in terms of spending ability than in your 20s and even 30s.4

I have previously calculated that a family of four renting for $800 per week with a single earner with a HECS student debt needs to earn at least $153,000 per year to be as financially well-off as a home-owning age pensioner household (ignoring their assets and only considering their income flows).

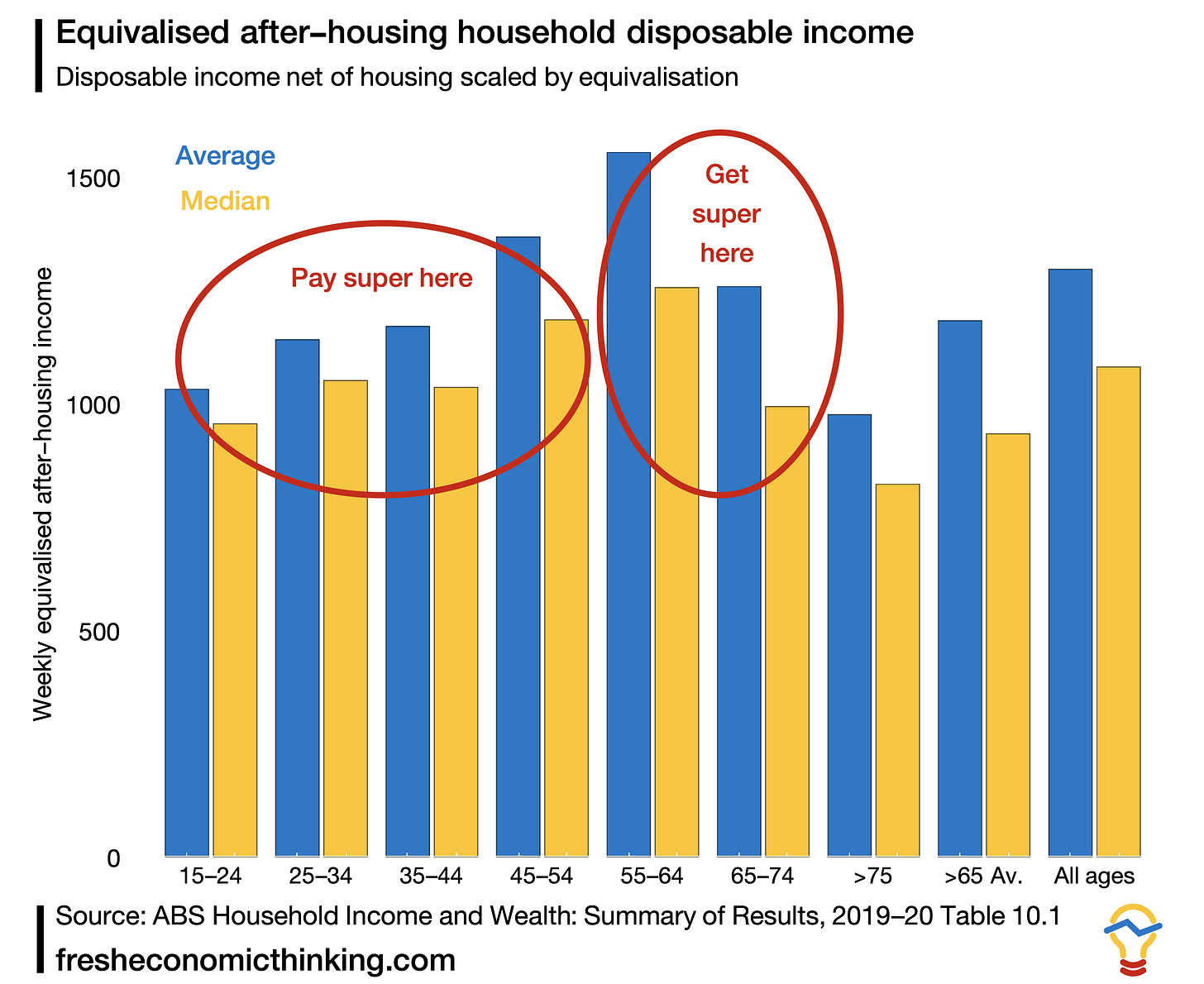

The data is quite clear on this, as the chart below shows.

After-housing average incomes scaled by household size (which is what the term equivalised means) are higher on average for those over 65 than for those under 45, though the median is a touch lower.

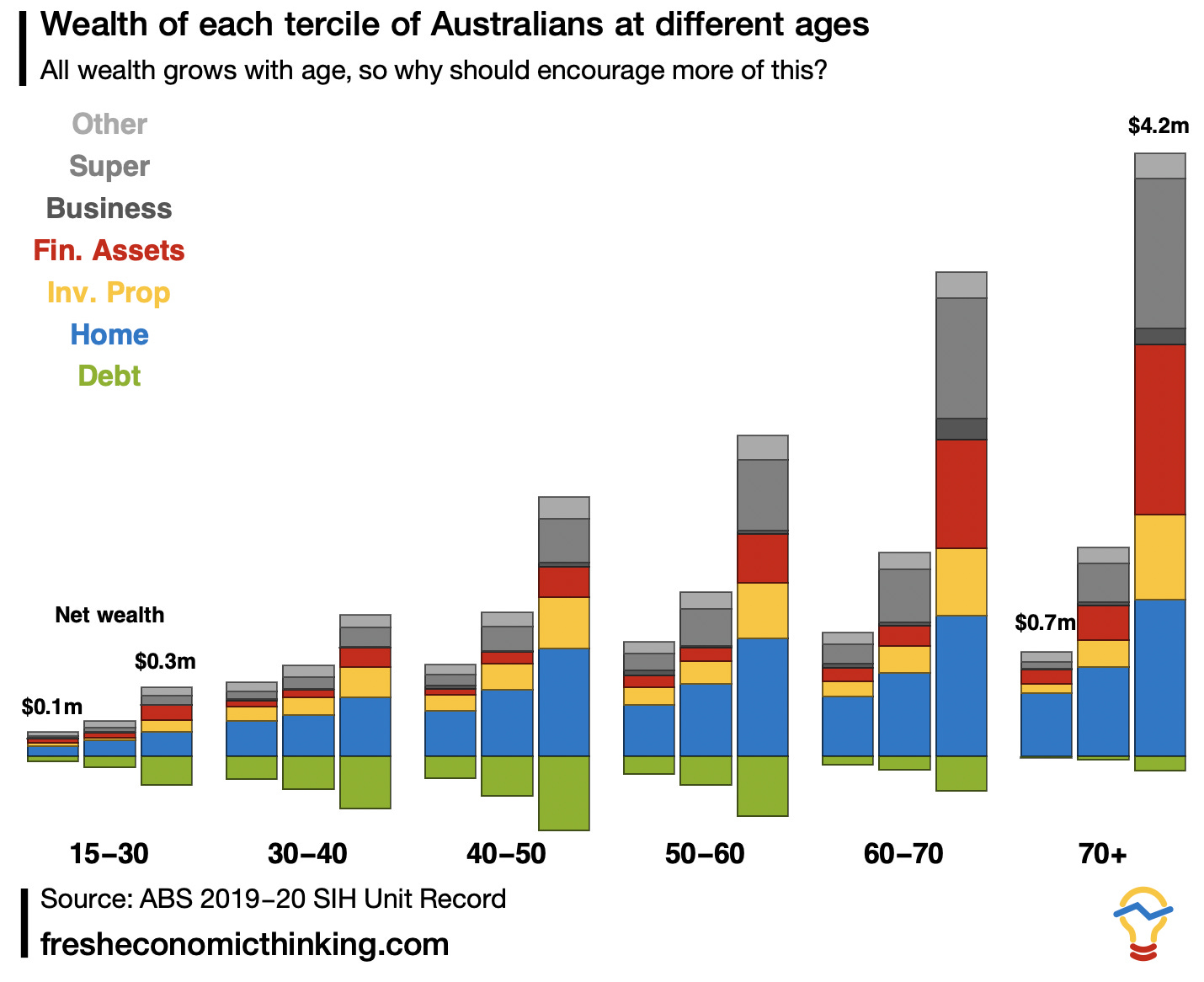

If we look at wealth rather than income, the age divide is more accentuated.

The chart below shows the per household wealth for each tercile (lowest third, middle third, and top third of households by wealth) across the age distribution. It shows that even outside of superannuation, wealth grows enormously over time as households accumulate assets and pay down debts.

Notice here that superannuation predominantly accumulates to households in the top third of wealth who least need to save for retirement and would save a similar amount without superannuation.

This RBA analysis from back in 1995 found that about three-quarters of superannuation was offset by reductions in saving elsewhere, and in 2004, another RBA analysis found that non-superannuation savings were reduced by about half of superannuation savings.

In short, a lot of superannuation is not increased savings, but merely reducing tax on savings that would have otherwise taken place by high-income and high-wealth households. This is the economic logic behind recent policy changes that reduce tax breaks on high-balance superannuation accounts.

Some of my previous views on the lack of income smoothing are here.

3. Superannuation soaks up economic resources

Efficient taxes and regulations are those with low administrative costs relative to the benefits provided.

Consider superannuation versus the age pension.

Fees alone for superannuation are around $30 billion per year. That covers the cost of all the roughly 50,000 people who work in the sector in various capacities, plus all the capital overhead.5

What is the benefit of the system?

Currently, the superannuation system is providing $55 billion per year in pension-style regular payments to members in retirement, and about $65 billion in lump-sum withdrawals to members. That means that the majority (54%) of withdrawals out of superannuation are in the form of lump sums, not regular income payments.

Can we consider lump sum withdrawals as a policy benefit of superannuation? Or is that a symptom of the system being used as a tax shelter for saving that would otherwise occur anyway?

I suggest more of the latter, meaning the retirement income benefits are much lower than we usually assume. And the economic costs of superannuation are much larger than most of us imagine.

To give some perspective on those $30 billion annual administrative costs, they are about half of the astronomical cost of the total National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), which is edging its way to $60 billion per year.

Total fees for superannuation are also about 55% of the total cost of the Australian military, which is getting a record $55 billion of funding in 2025, though the total superannuation workforce size at 50,000 people is similar to the military.

But super fees are still much higher than the cost paid by all Australian households for electricity each year, which is about $20 billion (or about $27 billion for all household energy). We have huge political debates about which electricity grid and generation method is cheapest, but the whole system, even if it contains a lot of waste, costs half as much as the superannuation system.

In contrast, the age pension’s benefits are large, and its administrative costs are a bargain.

The age pension system pays out nearly $60 billion of regular payments each year, with an administrative cost for the whole Human Services Department welfare apparatus being around $6 billion (see Tables 5.9 and 5.9.1 here). This covers not just the cost of administering the age pension, but all welfare payment programs. And guess what? It takes only 33,000 workers to run the whole welfare system, much fewer than running the superannuation system.

But what about the budget? Doesn’t superannuation “save the budget” and give us something more than would otherwise be possible due to its compounding returns?

No.

First, superannuation also costs the budget by shielding incomes from taxation. An estimated $45 billion per year in extra tax would be paid in the absence of superannuation, which is not far off the total cost of the age pension.

Sure, that is probably a generous estimate given that other financial structures would be used by those with large balances who benefit most from superannuation’s generous tax treatments. But it gives some idea of a world where your superannuation component of income is paid into your normal bank account, taxed normally, for you to then save or spend as you please.

Some people think that the cost of running the superannuation system is low because they compare it to the value of the assets owned via super funds. But that is not the right comparison, as I explained here.

The value of the assets in superannuation is merely a market estimate of the total value of future income generated. The age pension is an asset to every recipient, but no financial ownership claim represents the value of each person’s age pension. We could create such an asset, call it a pension bond, and give one to each resident at birth. If pension bonds could be traded, they would be priced, and the total value of them would probably be in the trillions.

4. Super reduces overall investment incentives

When the economy looks like to be slowing, we don’t encourage people to stop spending and save more, or put more money in their superannuation.

We encourage people to spend.

We use the government to spend more than it takes in taxes. We lower interest rates to get households and businesses to spend more than they make by borrowing. And during COVID, we let people withdraw from their superannuation to spend.

This spending is what encourages economic growth by increasing business turnover, justifying new capital investment.

Currently, the net payments into the super system are about $50 billion per year. That is, those paying into super pay about $50 billion more than what those who withdraw take out. This is a drain on spending, slowing economic activity and growth.

You can see the effect by imagining the situation where compulsory super is doubled.

It would quickly reduce consumption and investment spending by households, shrinking large parts of the consumer economy. Orders would be cancelled. Business expansions postponed. Aside from financial managers, most businesses would be up in arms about it!

Macroeconomically, compulsory superannuation slows spending, slows growth, and hence makes the whole economy smaller than it otherwise would be right when we expect it to be larger to help support a higher share of non-working elderly. This is counterproductive.

Some people argue that, because superannuation accounts compound in value over time, this somehow overcomes such undesirable macroeconomic effects.

But this is an illusion.

The tax system also grows at a compounding rate with the growth of the economy and the businesses in it. We just don’t record that value anywhere. After all, if the company shares owned via your superannuation fund rise because businesses are growing and are more profitable, then so too will taxes automatically rise and compound as they are levied on these same economic activities.

I explained this before here, and I think this quote sums up the main point.

The compounding returns from ownership are merely mirroring, or representing, the compounding returns to the overall economy. This is the same economy that is the source of taxation. Taxation itself is a compounding source of funding in the economy.

5. Super encourages early retirement

Most superannuation withdrawals are paid as lump sums, which you can do after age 60 if you stop working (the super preservation age was previously 55 and the age pension age was 65, but both have ratcheted up in recent years).

The seven-year gap between when you can spend all your super (age 60) and get the age pension (age 67), encourages people to stop working earlier, spend their super on travel, home renovations, cars and caravans, or on their children, and then get the age pension when they turn 67.

Every financial advisor understands this.

While superannuation as a system is meant to help us deal with fewer old people working, it in fact encourages more people aged 60 to 67 to stop working.

What do people do when they withdraw their superannuation as a lump sum?

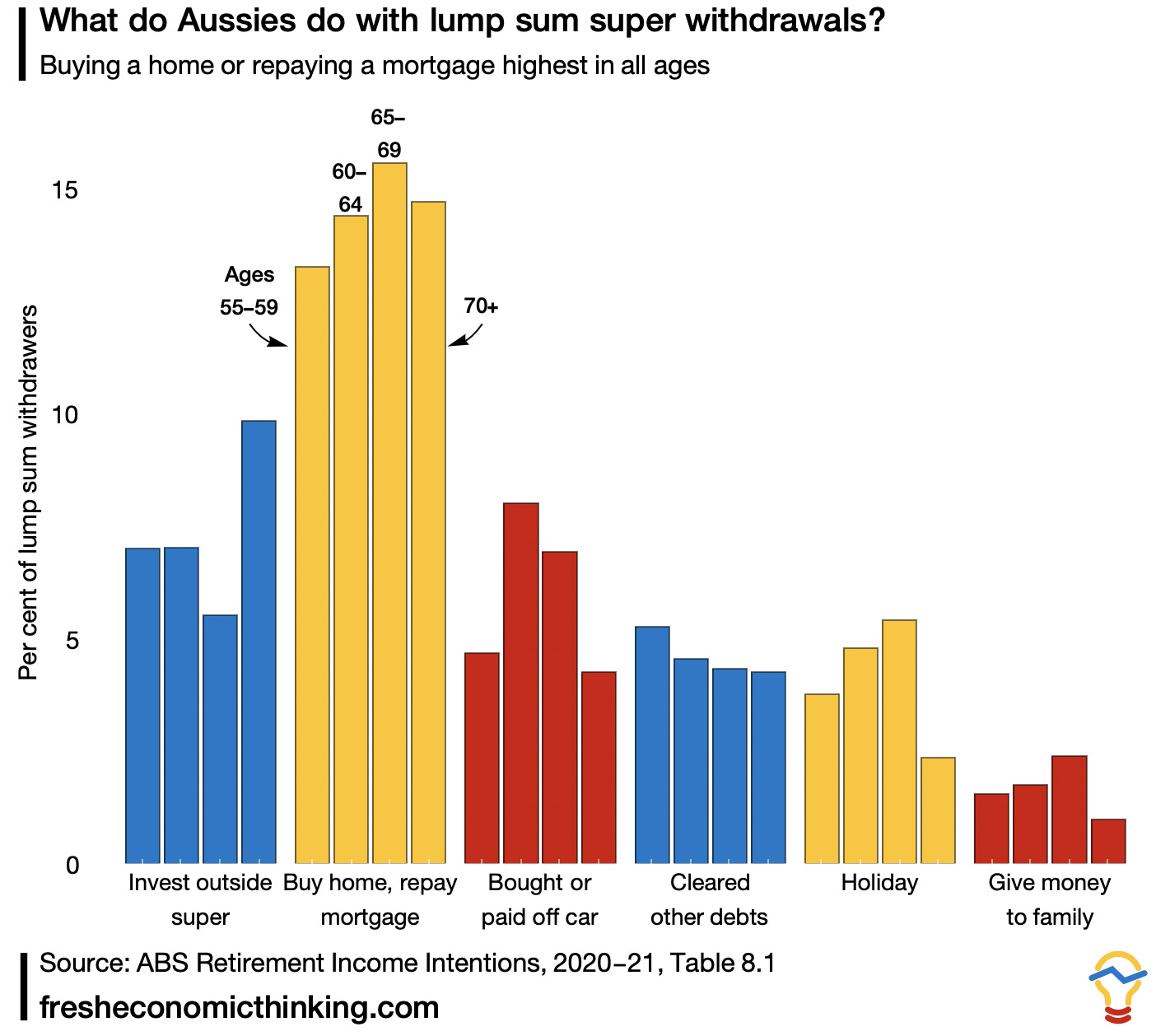

The chart below shows the main uses of lump sum funds withdrawn from superannuation accounts for different age groups at the time of withdrawal. The most common use of super withdrawals is to buy a new home or repay the mortgage.6

Other uses of lump sum withdrawals fit the general financial advice to get one’s pension-assessed asset balance down—cars and holidays, clearing other debt, and giving money to families.

In fact, one superannuation lobbyist promotes how great superannuation is because you can get it and the age pension! Amazing stuff. Here’s what they say.

Having super does not automatically exclude you from the government’s age pension. That’s because super was never meant to replace the age pension – only supplement it. Many people will continue to receive the age pension alongside their super. For example, some people with super will receive the full pension, and depending on how much super they have, some will receive a part-pension. And some will have enough super they won’t need the age pension.

So what?

I think a common confusion in both the economic and political analysis of superannuation arises because people see saving as a positive thing. Full stop. No further questions.

But it is not. We need to start with the question, “What is the purpose of money”?

Saving provides a useful buffer stock to deal with unexpected variations in income and expenses if you can rely on that buffer to be there. But by shielding superannuation from being used for unexpected spending during the most important years of your life, you are removing almost all the benefits of a savings buffer, only for it to apply when you are also eligible for an old-age income insurance system.

Saving is not good for its own sake.

This is why we have many hardship provisions for super. No point dying young with a super balance!

In fact, because superannuation can be withdrawn as a lump sum and spent on anything, from holidays, caravans, and home renovations, to gambling, prostitutes, alcohol, it still relies on the same self-responsibility, saving and investment that it seeks to avoid through compulsion during working lives.

So why not save $30 billion in fees, free up 50,000 people to work in more productive pursuits, raise tens of billions more in taxes automatically, and let young people have more money when they need it by unwinding the system entirely?

We can then focus on how we best deal with working age poverty, the adequacy of all welfare, including the pension, and generally aim to improve the efficient, fair and functional welfare state that we should all be proud of.

As always, please like, share, comment, and subscribe. Thanks for your support. You can find Fresh Economic Thinking on YouTube, Spotify, and Apple Podcasts.

Interested in learning more? Fresh Economic Thinking runs in-person and online workshops to help your organisation dig into the economic issues you face and learn powerful insights.

Some people fear that the age pension won’t be there when they retire. Fine. Then save more of your money to deal with that risk. I personally think there is broad political buy-in for the age pension, and it has been one of the most successful welfare policies in history.

Poverty of those relying on business income is notoriously difficult to measure, as the source report explains.

As a quick sidenote, some people erroneously think that superannuation is something extra you get paid that would otherwise not be paid as part of your wages. If you assume this, then there isn’t a trade-off of having less when you are young to have more when you are old. But this doesn’t make any sense—100% of super can be converted to wages by requiring the same payments to be made to normal bank accounts if the policy were unwound. If you don’t trust that this would happen for some reason, then simply allowing people to spend out of their super accounts at any time would convert all of their super to spendable wages.

I will be interviewing Daniel Hess next week about fertility and density and other topics (if you have any questions you would like me to ask him, please email me). He wrote this provocative piece. I suspect that superannuation is part of the policy environment that favours the old rather than young families.

According to IBISWorld industry analysis — K6330 and K6419D — from a few years back. I can’t access the current year’s data as I currently don’t have a login, but if anyone else can, please let me know.

As a quick ballpark, about 60% of all super withdrawals by value are lump sum, and 15% of those who do such withdrawals use the money to buy homes (this is not a proportion of dollars but a proportion of withdrawers using the money that way). Since the value of buying a home is probably more than buying a car or a holiday, we can suggest that perhaps the dollar values are much higher than the proportions, then we have a range of 10-20% of all super is used to buy one’s homes (including repaying the mortgage), but only after age 55 (now 60).

Super is also used to buy housing in Self-Managed Super Funds (SMFS) as an investment. This is one reason that letting people use their super to buy a home when they need one, rather than in their SMSF or once they retire, isn’t strange or undermines the system and fits with the logic of income smoothing that super undermines.

> The seven-year gap between when you can spend all your super (age 60) and get the age pension (age 67), encourages people to stop working earlier, spend their super on travel, home renovations, cars and caravans, or on their children, and then get the age pension when they turn 67.

I can't believe the means testing for the aged pension is this shit.

lets assume that we abolish the superannuation system entirely, do we still means test the aged pension? Or we make it universal like other high income countries? As you said retirees are generally richer than the young. Even in the current system, the means testing for the aged pension is shit.

Personally I would have also liked to means test Medicare since that is also a transfer of money from the young to the old.

I have seen a few politicians on the right arguing similar things, though not from major parties.

A claim they also make is that you can't really talk about removing compulsory superannuation without understanding the political realities of the system. In effect, if you control such enormous amounts of capital then you have enormous influence. For example AustralianSuper has 341B under management. Its CEO and Chairman look to be (from a quick wikipedia glance) similarly politically aligned.

I haven't dug into (or thought about) this extensively myself, but wondering if you have any thoughts?