Finding the Money: Can a film about modern monetary theory change our economic debates?

Or does it lead us back to many of the same tricky trade-offs

Upcoming in-person events for The Great Housing Hijack (out on 27th Feb):

Melbourne: 20th March, 12.30pm John Cain Lunch with Per Capita

Canberra: 21st of March, 6.30pm hosted by The Australia Institute

Paid FET subscribers now get access to article voiceovers that can be listened to via the website, the Substack app, or your favourite podcast app (using the link sent with the welcome email).

I’m not an economist who follows a particular school of thought. Schools of thought usually coalesce around a single powerful insight, and I think we should be able to synthesise the best insights from many different schools of thought.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is one school of economic thought. I have found enormous value in it. Rigorous attention to banking, money and payment flows, is central to MMT, but too often overlooked by most economists, leading to many logical problems in their reasoning and policy advice (e.g. that we can pre-save using financial instruments to “fund” retirements in aggregate).

I credit MMT academics and writers for stimulating my interest in central banking and money creation and for my current habit of looking at both sides of every balance sheet. This corrected many of the wrong ideas I held about these topics that I picked up during my economics study, and which are pervasive today in the policy discourse.

Even central banks are trying to improve on this failure of the economics discipline. As the Bank of England explained ten years ago:

The reality of how money is created today differs from the description found in some economic textbooks.

…

This article explains how, rather than banks lending out deposits that are placed with them, the act of lending creates deposits — the reverse of the sequence typically described in textbooks.

…

While the money multiplier theory can be a useful way of introducing money and banking in economic textbooks, it is not an accurate description of how money is created in reality.

…

As with the relationship between deposits and loans, the relationship between reserves and loans typically operates in the reverse way to that described in some economics textbooks.

I now incorporate a proper accounting of money creation into my teaching using these central bank documents as resources, such as this paper from the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA).

Of course, I don’t think MMT provides a complete description of economics, and I have disagreements about some policy prescriptions that tend to travel with it.1

With that in mind, I want to offer my thoughts on a new MMT film called Finding the Money, a riff about how to respond to the political question of “Where will we find the money?”

Before I get into my notes on the film itself, the image below shows the upcoming Australia film tour dates (click it to be linked to tickets). I will be attending the Brisbane event on the 10th of March 2024.

The film’s big ideas

What Finding the Money (FtM) does well is articulate the nature of money as a debt relationship—an IOU (“I owe you”)—not a type of good or token (as I have previously explained here).

This is important.

FtM goes into depth about the origins of money and the need for some kind of social authority to enforce the value of a unit of measurement of the IOUs that circulate as money. This origin story is valuable for helping people change the way they think of money.2

It helps to then take the next step in understanding that just like a government bond is a debt to the issuer, and an asset to the holder (like any IOU) so too are money deposits held in banks a debt to the issuer (either a private bank or the central bank) and an asset to the holder.

The symmetry is a crucial insight and the film reiterates it multiple times. David Andolfatto even says in the film that the “debt clock may as well say private sector wealth” because the debt on that clock is made up of government bonds (assets) held by the private sector. The IOU is a liability to the government and an asset to the private sector holders.

This story allows us to understand what would otherwise be quite shocking. FtM notes this about the hard-earned taxes people and private organisations pay: “When they pay their taxes the government just burns it.”

Huh?

That sounds weird. It must be wrong, right?

But it makes total sense if you think of money as an IOU relationship and not a token. When you pay back an IOU, the paper records of that IOU held by both sides of the relationship are thrown away. It’s the same with money. When you pay back your home loan, the bank throws away the deposits that you repaid the loan with alongside the loan liability. They cancel out.

Money disappears.

In the same way, when taxes exceed government payments to private entities, the amount of IOU money circulating in the economy falls. The taxes make money disappear.

Although I can’t find it now [UPDATE: found if here], there was an interesting video produced by the RBA a few years back that explained what happens when payments are made from banks to the Treasury. Since the Treasury doesn’t have a reserve account balance at the central bank when you pay taxes, the money simply disappears—not burnt exactly, but it is cancelled out in the accounting system of the banking sector and central bank.

This insight helps explain why measures of total deposits held by households can only rise if there is more borrowing in aggregate—either by individuals from banks or by the government. People can’t just stop spending and save and increase the deposits at banks. Only extra borrowing increases total bank deposits.

This is why the MMT position is that for the private sector in aggregate to save financial assets, or in other words have a surplus, then the public sector must have a deficit to match. After all, there is no one else to have a surplus with.

“What’s the strength of MMT? It’s monetary operations, no doubt about it”

Viewers of FtM will get a laugh from some of the interviews. One example is when esteemed economist Jared Bernstein forgets how lending works and fumbles with various wrong explanations.

Another is when the former comptroller of the United States for 30 years says that it is not true that money is listed as a liability on the central bank’s balance sheet.

Are reserve notes accounted for as liabilities? I don’t think so. No.

But they are of course.

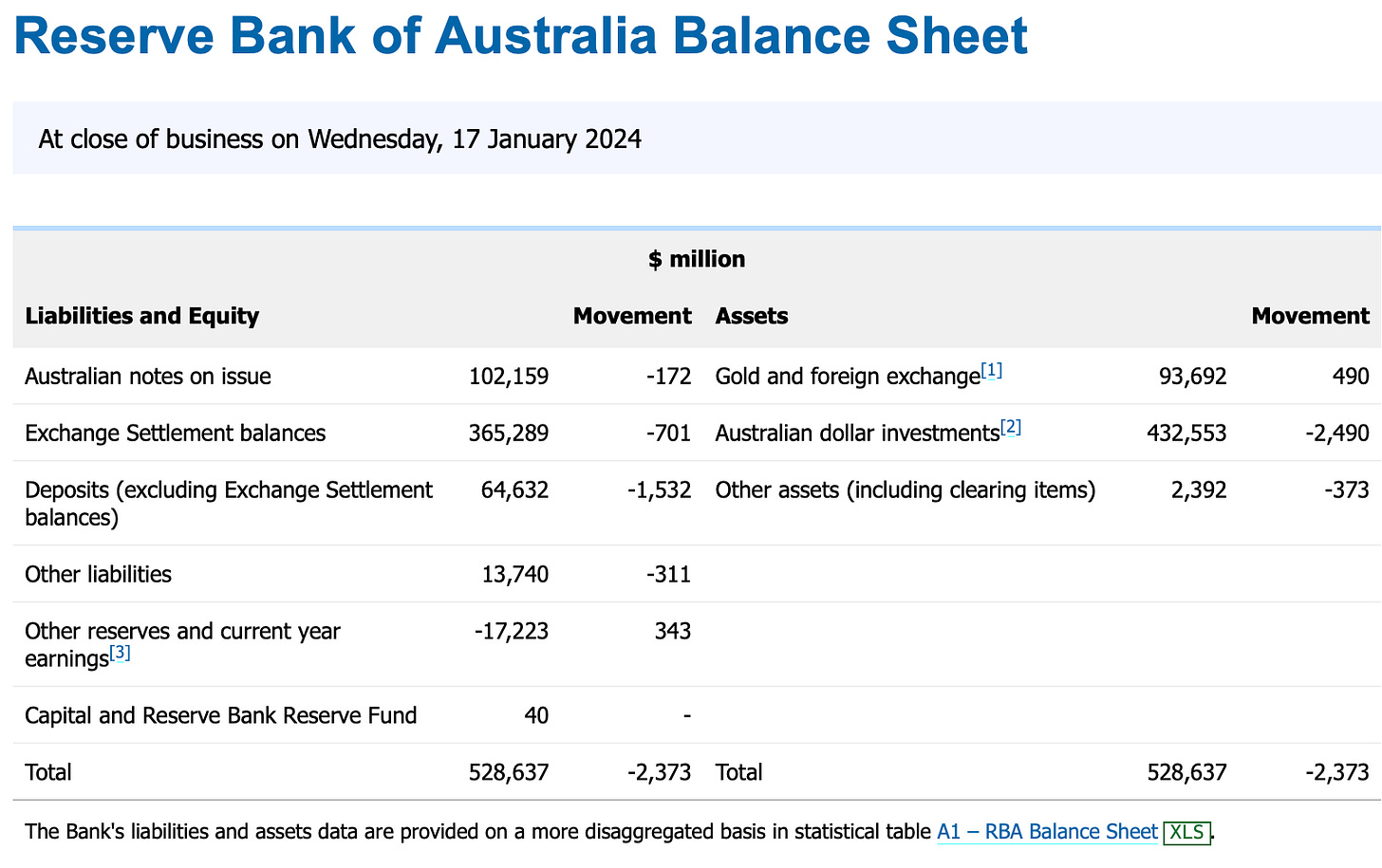

There are two types of money recorded as liabilities on the central bank balance sheet—bank notes (physical cash) and exchange settlement account (ESA) balances (known as reserves), which are deposits at the central bank held by private banks.3

Here’s the RBA’s balance sheet. You can see the $467 billion of notes and ESA balances right there. That’s the flip side to our physical cash assets—they are a central bank liability.

A final useful insight you will get from FtM concerns the popular economic idea that governments running budget deficits (spending more than they tax) push interest rates up. Harvard economist and economic advisor to President Obama, Jason Furman, espouses this view in the film. But Stephanie Kelton laughs at this claim and says that “the interest rate is whatever the central bank wants it to be.”

Which makes sense. Central banks really do control interest rates. That’s the reason monetary policy can operate at all. So you can choose to have low interest rates and huge deficits, as happened during COVID. It might not be a sensible macroeconomic setting to operate this way, but can certainly be done.

In an MMT lens, deficits can also be too small.

For there to be enough spending in the economy “the normal situation for a currency issuer is to be in deficit.” Since the private sector wants to save, it stops circulating money. So to keep up spending the government must step in. This is a subtle insight, but one the film does a reasonable job of introducing. And honestly, communicating any of these ideas in an entertaining film is a challenge!

One strange thing in FtM is that it takes an hour before we get the quite important detail that private banks also create money as well as the central bank.

This appears to contradict an earlier part of the story of money, which is that a currency-issuing government must spend first before it collects taxes. Maybe this is helpful rhetoric. I think it is confusing. There is no sequence. Governments are spending and taxing continuously.

How does this knowledge help?

If the idea of money as an IOU and its forgotten symmetry is the main takeaway for the audience of this film, then it is an important contribution. But it still left me with some questions.

How does a better understanding of the inner workings of the monetary system change our economic reasoning?

For example, even though the monetary budget constraint that occupies our minds is not real, nor even an accounting problem, the physical limits of the still economy are very real.

No political party or nation acts as if the government budget is a constraint on their spending. They deficit spend, just as MMT describes they probably should as a “normal” course of events.

Although Jason Furman stumbled over monetary operations and interest rates, he was right that MMT often brings you back to the same trade-offs—is there enough productive capacity to deficit spend without generating excessive inflation?

MMT says the binding constraints on money printing are physical production limits that, when reached, result in inflation. It’s not the budgets themselves. Yet that’s also the constraint of mainstream economics when it “looks through”, or ignores, money altogether. The mistake of mainstream economics is to conflate monetary budgets with physical resources.

George Selgin from the CATO Institute asked insightful questions in FtM, such as: “How would MMT people propose to control inflation when needed?”

I suspect MMT advocates would suggest more taxes as a way to reduce spending when inflation is high. The tax system does automatically raise more in an inflationary environment (known as automatic stabilisers), so that helps. Would more active tax changes be needed? That seems a tough ask, just as spending restraint is often tough politically in inflationary environments.

In the film, a surprising idea espoused by Stephanie Kelton is that “You can actually spend money and reduce inflationary pressures.” That’s a real challenge to the orthodox view of how physical limits to resources matched with extra monetary spending create inflation. I think it’s even a problem in the MMT “soft” constraint view too. How does knowing monetary operations make this make sense?

Fadhel Kaboub expands on this logic:

Money that builds new capacity building mass transit and converting to 100% renewable energy.

So housing, healthcare, energy, and transportation, the green new deal includes those areas specifically not because it’s the favorite shopping list of the progressive movement, because these are the sources of inflation.

We’re going to include them in the Green New Deal because that’s how you increase availability and reduce cost.

This seems wrong to me because it overlooks the inter-relationships in the economy. The spending required to build mass transit or green energy still requires people, and resources to be taken from elsewhere in the economy. And it is inconsistent with the answer to the next question.

Lua: But what if we want to increase government spending and the economy is already at full capacity?

Stephanie: Then they have to be freed up, or created. How do you do that?

Here, we get to the nuts and bolts. If you want to spend money on something, you need to free up the resource inputs from elsewhere. The “hard” budget constraint says you do that by spending less on other things. The MMT solution gets to the same outcome but with the addition of noting that improving productivity is one way to free up humans and other resources.

Yet isn’t this also the standard economics view?

If we want a big government spending program, such as a large welfare policy change, this will need taxes to fund it. If the gap between the “hard” budget limit and the “soft” inflation limit is $10 billion per year, and a program that costs $20 billion per year is implemented, then half must be raised in taxes anyway. And if there is already deficit spending of $10 billion due to other government commitments, then every dollar of new spending needs to be raised in taxes to avoid even the “soft” physical limit.

So MMT takes us back to this same physical trade-off that is a key insight of all schools of economics.

MMT doesn’t solve all our problems. Being able to create money doesn’t solve all our problems.

But finding the money is often the least important challenge. The real challenge revolves around how can we organize our collective resources, to allow humanity and the rest of the living world to thrive, within planetary boundaries.

If we have a vision for a better future, money is not the scarce resource we need to go out and find before we can start building it. Money is the organizing tool we can use to mobilize our people and real resources to make that vision a reality.

There should be no disagreement about this. The fact that this is not the claim of all schools of economic thought is the real puzzle.

As a final note, the “so what” of MMT seems to be that without the “hard” budget constraint governments can deficit spend to support full employment. I’m not sure that this contradicts mainstream macroeconomics either, only some widely believed myths about the macroeconomic costs of debt, which MMT rightly dismisses (debts are also assets after all, as noted earlier).

This is why a job guarantee policy, where a government agency is tasked with employing everyone who doesn’t have a job, is a central idea of the MMT school of thought. But for the life of me, I can’t see how the understanding of monetary operations would lead to that policy idea, rather than any other form of welfare system.

The job guarantee idea doesn’t get much of an airing in FtM. I think that’s fair enough. I’ve found it a very strange idea to get packaged with insights into monetary operations.

For me, the big takeaway from FtM is not that we can spend without limit. It is that money is a two-sided debt relationship created either by private banks or the central bank, that can be harnessed to direct spending and investment in the economy in any way we choose, so long as we have the real resources available.

This shouldn’t be controversial. John Maynard Keynes wrote exactly this explanation in 1940 when he explained how to “pay for” the war. Abba Lerner explained similarly.

Lastly, I think there is a hidden political miscalculation behind MMT which you might pick up on during FtM. Since all governments are already deficit spend, the budget constraint surely has never been a real political concern. Deferring to budgetary pressures just makes for convenient politics.

If you’re a politician or political party and you don’t want to spend money on something, you talk about the budget constraint. When you do want to do something, you don’t. It avoids the important discussion about social priorities that your side of politics might risk losing.

As I said at the beginning, it is worth appreciating the big insights from each school of thought in economics and integrating them into a coherent worldview.

FtM communicates in a surprisingly effective way some of these key insights from MMT and I highly recommend it for that reason.

Such as job guarantees, which can seem like workfare and don’t appear related to the important core MMT observations about money.

Another useful account of this more accurate origin story of money is the late David Graeber’s book Debt: The First 5000 Years.

There are 20 financial institutions in Australia with access to this “central bank money”