Money is not a token. It’s an accounting system.

A short lesson on money and why crypto makes no sense

There are two views on money.

Money is token, or object, that is a special easily exchanged good

Money is an accounting system

The first token view of money is implicit in standard economics. Money is just another good and we use this special token good as the yardstick to measure relative prices, but otherwise, there is nothing special about money.

Under this view of money, a digital version of a physical token or object makes sense. This is the logic behind cryptocurrency, as Dr Saifedean Ammous explains in the podcast below.

He says

The thing that defines money is that it is a good that you don’t buy for its own sake — because you want to consume it itself, or because you want to employ it in the production of other goods, which is what capital goods are, so we have consumption goods, we have capital goods — money is distinct from those two, because it is a good that is acquired purely to be exchanged later on for other goods. So it’s not something that you acquire for its own sake — you acquire it so that you can then later on exchange it. And that’s a market good like all other goods: you acquire food because you eat it, you acquire a car to move you around, you acquire money so that you can exchange it for other goods. And that’s something that many people have a hard time grasping of: the concept of money as a market good. But it is a market good just like all others.

But this view is wrong.

The second credit view of money is the correct one. Money is the name we give to record-keeping accounting conventions. Under this view, it is important that the expansion of account balances (new money printing) is flexibly enabled, and transactions between account holders can be easily reversed.

The two things that many believe to be desirable features of blockchain systems—fixed supply of tokens and irreversibility of transactions—are undesirable features of money.

What is a credit arrangement and how does it create money?

When a private bank extends a loan it creates a type of money in the form of a deposit with that bank. So too does the central bank crediting new money to people’s bank accounts. Both are money printing. Both are desirable features of our monetary accounting system.

Here is a simplified version of a bank balance sheet. The deposits of account holders are a liability of the bank. The loans the bank has made are assets, as are the balances of the bank’s Exchange Settlement Account (ESA) at the central bank. Just like a customer has a bank deposit account at a private bank, each private bank has a special deposit account at the central bank.

This bank makes money when it makes a loan. In the jargon this is known as “liquidity transformation”—the bank converts an illiquid asset (the debtor's future ability to repay) into a liquid one.

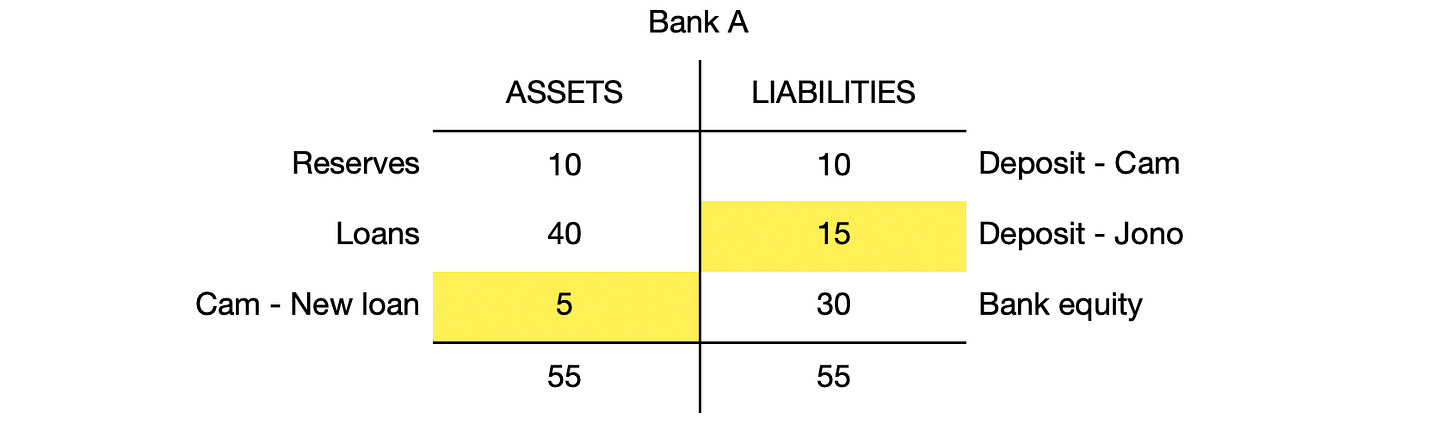

Let us say that the bank customer, Cam, borrows $5 to buy a car from the bank’s other customer Jono. The bank simultaneously extends its balance sheet on both sides. On one side it creates the loan with a $5 value in the asset column, and on the other creates a $5 deposit in the liabilities column (bank deposits are a customer asset and a bank liability). Initially, that liability could be assigned to Cam, but then when Cam buys the car, the deposit transfers to Jono (i.e. the bank now has a $5 extra liability to Jono).

The outcome of this is shown below with the changes shaded yellow. Notice that because money creation involves creating assets and liabilities jointly it is sometimes called balance sheet expansion.

The reverse operation of money destruction, or balance sheet contraction, happens when bank loans are repaid. It’s just the nature of money as record-keeping accounting.

The money created in this example is a specific type of account balance, a bank deposit. Yes, we think of this as money. But there are other types too. Each bank has an account at the central bank. This is a different type of money known as an Exchange Settlement Account (ESA) or a bank reserve. Every time credit is extended between businesses, this is a type of money creation, and when credit is repaid, this is a type of money destruction. In general, every IOU created in any account is its own special type of money. It might not be as useful as bank deposit types of money, but payments can be made with them. After all, money is the name of the system of accounting.

The beauty of money is that as the economy grows, so do the bank balances of individuals and companies. When new loans are created to fund capital works that expand the capacity of the economy, this also creates more money.

This is a very desirable feature of our credit money system. Money printing happens all the time.

How are payments with money actually made?

Settlements between banks require 1) communication and 2) a balanced accounting for the payment. As we saw above, when a payment is made between two deposit account holders at the same bank, all the bank must do is record internally a change in who has claims to which deposit liabilities. An easy task.

But between banks things are different. A bank won’t accept the liabilities of another bank (a customer deposit) without also receiving a counter-balancing asset.

So to do that, banks need to communicate the identity of the recipient who should have their deposit account credited, and offer a settlement medium, which is to say, a corresponding asset.

That could be a banknote, which is a promise from the bank. Essentially one bank says to the other “credit your customer this amount in their deposit account, but for you to do that I offer you a loan from my bank to put in your asset account”.

At some places and times in history, the settlement medium was a physical asset like gold. But of course, the choice of gold is as arbitrary as any other material. The use of gold as a settlement medium evolved because it was rare and valuable outside of the money system, hence limiting forgery risk.

These days, however, banks settle payments between them using central bank ESA accounts. That is, Bank A will provide the other with a list of deposit accounts to credit at Bank B, and also offers the same amount of ESA balances to Bank B from Bank A’s account at the central bank (known as reserves).

I have shown the accounting that occurs when a payment is made between two banks in the below table. Here, the $5 that Jono received from Cam when he sold it car is being paid to Jack who has a deposit account at Bank B.

Bank A communicates to Bank B to credit Jack’s account and as a settlement medium provides $5 of its ESA balances at the central bank. Bank A also tells the central bank to credit Bank B with $5 of its ESA balances. At the end of this payment, all the accounts balance as they did prior, but the composition of assets and liability for each entity changes.

Settlements like this historically between banks happened overnight after the daily net payments were tallied up from each bank. These days, banks have mostly transitioned to real-time inter-bank settlement so that bank deposits are even more cash-like in terms of the receiver getting their payment instantly rather than the following day.

What about cash? Is that a token?

How does physical cash fit in as a settlement medium? Doesn’t cash show that despite all this crediting and debiting of account balances that token view of money makes sense?

Cash is just a useful and mobile way to coordinate with other parties to credit accounts.

To be clear, cash is a physical representation of a liability of the central bank. Cash is not “in” your deposit account to be withdrawn. Cash is the name of a different part of the central bank’s accounts, though similar to the ESA accounts.

What happens when your bank gives you cash is that it makes a payment from your deposit account to the central bank, just like if you had transferred your money to a deposit account at another bank.

You now hold in your hand a deposit at the central bank.

That cash is physical is of no real consequence. Imagine that you ripped out from your printed account statement at the central bank the rows of your account and swapped them with others. That is what cash is. A physical representation of the balances at the central bank.

Cash is credit too.

When crypto tries to replicate cash it misses this key element. Instead, it thinks of cash as a token, a commodity. It tries to replicate a commodity view of money by recording ownership on the token itself. Imagine that commodity is gold bar. Crypto solves the problem of ownership by digitally replicating a process whereby gold must be stamped with the owners name, and when it is spent, you cross off your name and stamp the name of the person you are giving it to, with the date of the payment.

But money is a record of a credit relationship, not ownership of a physical object.

Cash, anonymity and reversibility

Are cash transaction anonymous and irreversible? Sometimes. But not always. If I buy my groceries with cash but then realise they have charged me twice for some items, that transaction will be reversed. Why would you want it to be otherwise?

In fact, we have a whole area of consumer law that requires all purchases to be reversed under certain conditions, and these laws would apply to cryptocurrency payments also.

Indeed, the fact that cash is not so easily reversible is one of the risks. That’s why you don’t pay cash to people you don’t trust before receiving the item you are purchasing. This is why people like to use credit cards or other payment methods where there is some insurance against being scammed.

I don’t think it is possible to change the nature of the money payments relationship between two parties that need trust. Having a reliable trustworthy payment system is a non-issue. It is the reliability of the partner in the exchange that is always the issue.

In sum

To understand how to improve the functionality of money, electronic or otherwise, you need to have a clear understanding of the current monetary system—how it functions and why it does. You need to know the economics of what is a desirable money system.

Unfortunately, the crypto craze seems to have very little of this. Many “believers” have doubled down on the idea that money is a token, and that money printing is bad.

This is an overly simplified view.

The fact that we have seen more take of payment systems like PayPal, which provide a middleman with insurance for payments, rather than crypto, which prides itself on having the opposite features, suggests that perhaps the craze is not rooted in reality.

While it is perfectly possible for physical objects to be used to trade with other objects and to settle transactions, like cigarettes in prison, the limitations of that approach are why they do not last long or become widely adopted.

Oh, lastly, I have a bet with Jason Potts that has been going since 2017 about when cryptocurrency will become a useful payment method. The bet had a 5-year window that is up on 19 September 2022.

The credit view of money allowed me to make some predictions that I think were quite good.

Here are the conditions.

I [Cameron] will lose the bet if, as at 19 September 2022, Bitcoin (meaning Bitcoin or any other cryptocurrency not backed by a national banking institution) meets all of the following criteria.

1. Bitcoin can be used to buy groceries in a physical store in my suburb where prices are posted in Bitcoin and not simply converted from AUD pricing periodically.

2. More than three listed companies in Australia pay salaries in Bitcoin (or have an option to), and advertise their salary rates in Bitcoin (i.e. you do not just get paid AUD converted at the going exchange rate each time).

3. At least one OECD country accepts Bitcoin for income tax payments and will calculate tax obligations in Bitcoin (not convert from the local currency to Bitcoin).4. Jason Potts is being paid in Bitcoin at a fixed Bitcoin price (not simply converting an AUD salary to Bitcoin).

Loser pays the winner AUD 100 at an event the loser organises in their city that involves lively discussions, debates, and socialising.

While you are here, I discuss these ideas in more detail in this episode of the new Fresh Economic Thinking podcast. Please find it in your favourite podcast app.

Good article Cameron!

One point is not stressed enough - the importance of the clearing system! This is what keeps the whole system in check. It's not free for all and there are limits on how much private money can be created. Good analogy is a personal credit card = license to print money- individuals can create money by spending into the economy (like banks giving loans) BUT, at the "end of the day" or 55 days, they have have to have the capacity to settle (if the bank only issues the money and doesn't balance with deposits from other banks they have to provide collateral for the loans they issued once the money is transferred to another bank).

One more thought, probably a more complex issue to address - what does money actually represent? Yes, money as "debt accounting system" can explain how it is created and reconciled but I am missing "a view" on how its "value" is determined. Sticks or rocks did not have intrinsic value but gold did. Both were used as money. And historically there were "systems" where other things were used as common "value" determination for trade. So that "exchange/trade" aspect of money must be a part of its explanation...

And then, why value of current money is inflating over time if it is a pure accounting reference? I guess, there is more to money than a single view can explain...

Hi Cameron.

Just catching up. Thank you for this. Some feedback.

1. I think both token and credit view are correct. We acquire money to exchange later on, no?

2. Table Bank A (before) - the total is 55, not 50, no?

https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_webp,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F41b25347-47bc-4d76-91ca-ac172b8c2b87_1718x1560.png

3. What do you think of the proposes USA ecash act?

https://ecashact.us/