Australia's HOUSING CRISIS was just an inflation pulse. It is over.

Poof! Just like that, the housing crisis is over. Or will falling rents and prices be the next crisis?

People love a crisis. Have you noticed? We are all drama queens.

The housing crisis has been a big topic lately.

So much nonsense has been written about housing under the crisis label that I felt the urge to write a whole book to straighten things out. Of course, I couldn’t help but join the crisis choir with the book title.

You could be tricked into thinking that we never have the right number of homes—there’s either a shortage or a glut. Prices are never right. They are either rising too much or falling too much. It’s always bad!

One reason there is so much confusion is our human tendency for attribute substitution.

This is the phenomenon where our brains take tough questions and substitute them for easy questions instead and assume the answer applies to the harder question.

“Are there enough homes based on what we would expect economically?” becomes “Was there a queue at my rental inspection on the weekend?” Answer the second easy question with a “Yes,” and then substitute that as the answer to the first more difficult question.

It’s bad reasoning. But it’s how our brains work.

But here's what everyone misses when they do this.

We have had a temporary global inflation pulse due to our COVID policy response that has passed through the housing market. It is the process of how inflation passes through the market that has led people to worry about a crisis—we have seen the process of rental adjustment via queues at rental inspections and misdiagnosed the problem as being the wrong number of homes.

In this article, I build on this brief story to provide a big-picture view of why there has been so much concern about housing recently.1

I then speculate about how these temporary adjustments to rents and home prices fit within the longer macroeconomic cycle and make some predictions for 2025 and beyond.

Read more about the underlying economics of housing markets.

Global inflation pulse

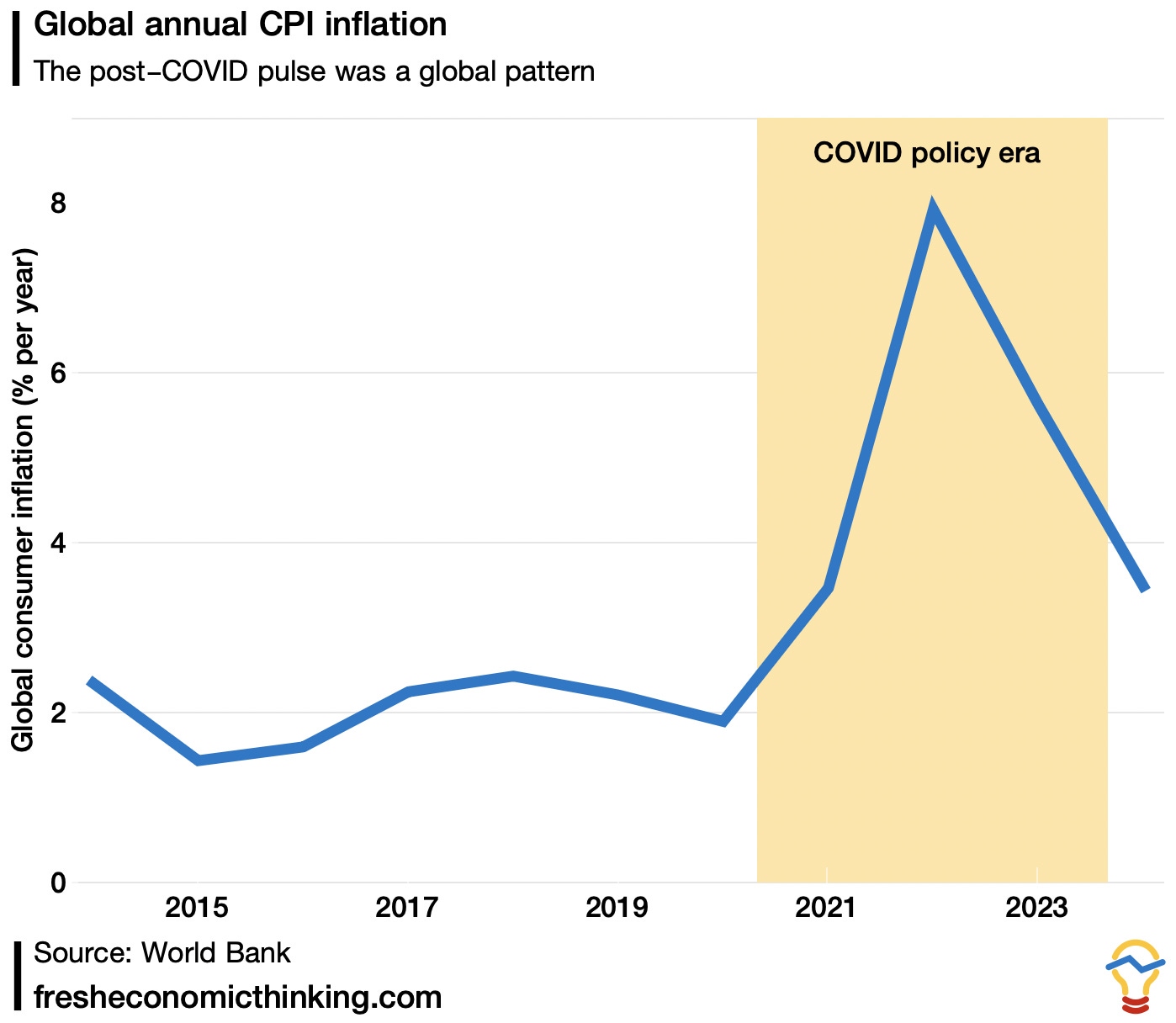

The first thing to recognise for understanding housing is the macroeconomic context of the COVID era. The rate of consumer price inflation surged due to a combination of enormous fiscal and monetary stimulus coupled with unprecedented physical disruptions to production due to border closures and lockdowns.

In the four years prior to COVID, global inflation was 8.8%. It was 20.2%, or 2.3x higher in the four years since.

This was a classic case of the economics of policy shocks and the inflation limits of stimulatory policy measures. It was a temporary effect that rippled through global markets.

Australia could not avoid some kind of inflation surge in this macroeconomic environment. Of course, our policymakers were as panicked as anyone and went overboard with their stimulatory measures, including JobKeeper, HomeBuilder, the often-forgotten Business Cashflow Boost, and zero-interest-rate monetary policy.

So we should expect to be at the higher end of global inflation trends.

There is also a geographic dimension to inflation that matters for housing. People left the cities and generated local housing prices and rental booms in unexpected places.

Now, let’s dig a little deeper.

The predictable housing rental price pulse

In 2023, I explained that Australia would see a similar inflation pulse to those in housing rental markets globally. I shared this chart.