Unpicking concerns about using superannuation for housing and retiring with a mortgage

Tightening up the debate with straight facts and fresh economics

Paid FET subscribers get access to this article, the growing charts page, and in May, the audiobook of The Great Housing Hijack via the FET podcast.

The debate about superannuation is loose.1

One controversial part of the superannuation debate revolves around the financial conflict between housing and super. If you save more of your income in the form of non-housing assets in superannuation it makes it harder to save more of your income in the form of housing that you occupy.

This is an indisputable tension (comment if you think otherwise).

But despite this indisputable trade-off, many people still think that allowing your income to be spent on housing, or any other goods and services, rather than superannuation, is a bad idea.

Two arguments dominate this side of the debate.

People are already excessively leveraged into housing, with mortgages lasting much later in life, so allowing this process to be amplified would be bad. As one news article put it: “What would a retiree live on if they pillage their super to pay off the house?”

Using superannuation to buy housing will increase home prices, making it harder for others to buy, and undermining the net homeownership benefits. As one news article put it: “Experts warn that letting first-home buyers use their superannuation as security to purchase a property could turbocharge price rises without a boost to housing supply.”

To be honest, these arguments once concerned me too. It took me years to take the emotion out of housing and see the underlying economics. Once you do this, you realise there that these concerns are not as important as they first appear—or not important at all.

Let’s examine the data and discuss the economics at play to see why these concerns are misplaced.

Leveraged lives and retirees with a mortgage

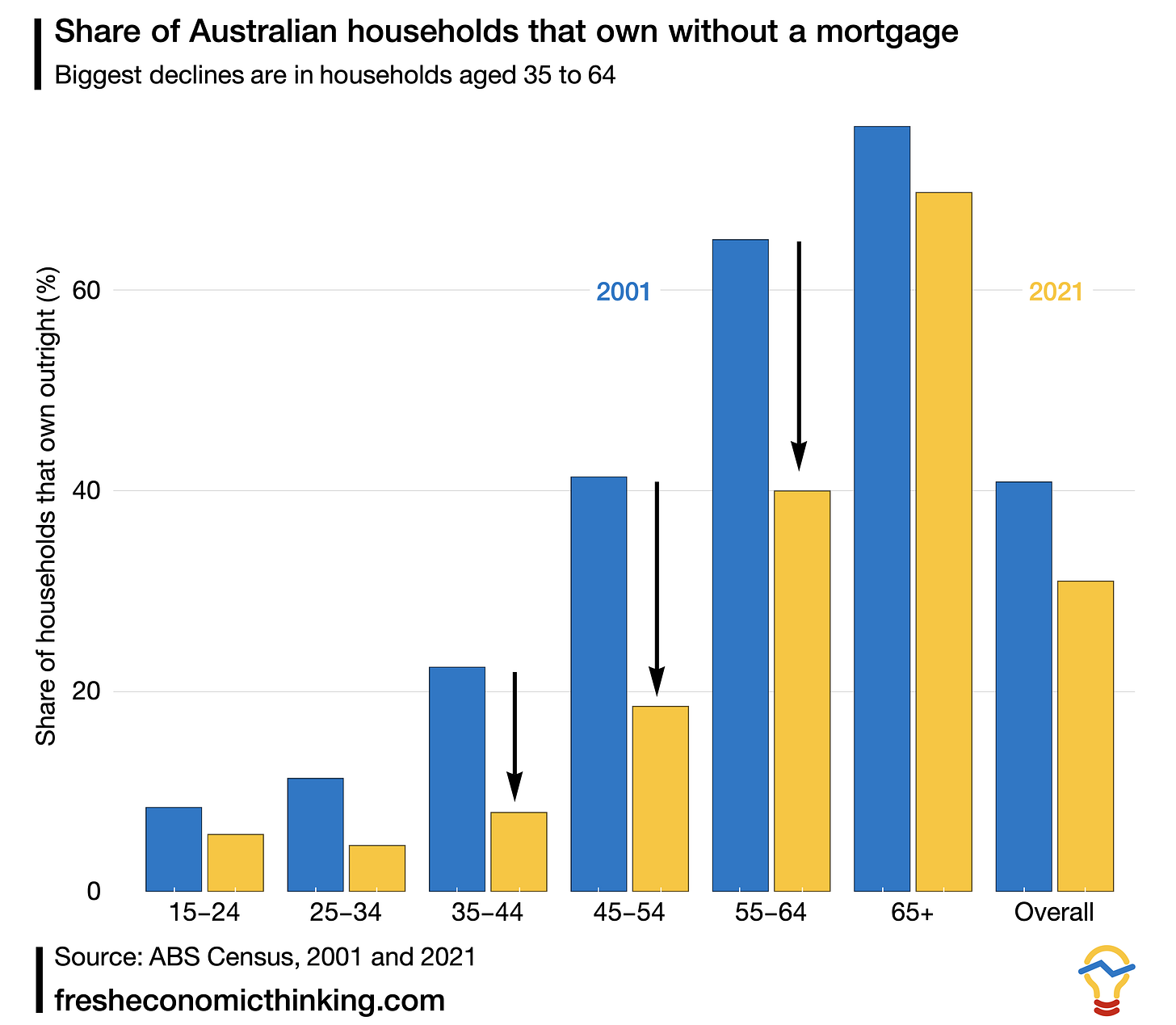

It is true in Australia that the proportion of households that have a mortgage later in life is rising. Below is a chart (hat tip to Avid Commentator) comparing the share of households that owned their home outright in 2001 and 2021 across age groups.2

A decline from 76.4% to 69.8% of those aged over 65 owning a home without a mortgage means an extra 6.8% of households mortgaged households. Over the same period, the share of households at any age with a mortgage increased from 32.1% to 36.8% or 4.5% points.

The bigger declines in homes owned outright are those aged 35-64.

In terms of owning a home with or without a mortgage, for those aged 65-69, the rate is about 80%. This is about the same rate as in the early 1980s. The peak of homeownership for this age group was in 1996 at 84%.

So the number of retirees owning homes is not dramatically changing. It is the proportion of them with mortgages later in life is rising, especially those in their late 40s and 50s.

What is missing from this analysis, however, is two things.

An account of the total balance sheet of those households

A recognition that longer lives are stretching out work and homebuying

Total balance sheets

Housing is just one asset that households have. And a mortgage is just one liability. Outside of housing, superannuation is one of the biggest assets of a household. In the last twenty years, the balances in superannuation have increased dramatically as has the proportion of people aged 65 and over with a super balance.

For example, in 2009-10, only 42.7% of people aged 65-74 had any superannuation. In 2019-20 it was 58%. That’s a 15.3% point increase in the number of people with superannuation in just a decade.

The balances also have been much higher.

In 2009-10, the median balance of a superannuation account of a 65-74-year-old was $159,000 and the mean was $328,000 in real 2019-20 dollars. In 2019-20, those same figures were $200,000 and $410,000 respectively (see ABS Household Income and Wealth, Table 12).

That’s a 25% real (after inflation) increase in the median and mean balances for each superannuation account holder on top of the 15.3% point increase in the proportion of superannuation account holders.

If you now take a couple household, one male and one female, both with the median super balance for their gender, that household saw an increase in super at retirement age from $282,000 in 2009-10 to $376,000 in 2019-20 or a 33.5% real (inflation-adjusted) increase in the value of this asset.

Detailed data from earlier periods is hard to come by, but this is the change over just one decade or half the period that saw modest increases in mortgaged homeownership at retirement age.

So which is bigger, the rise in mortgage debt or the rise in non-housing assets like superannuation at retirement age?

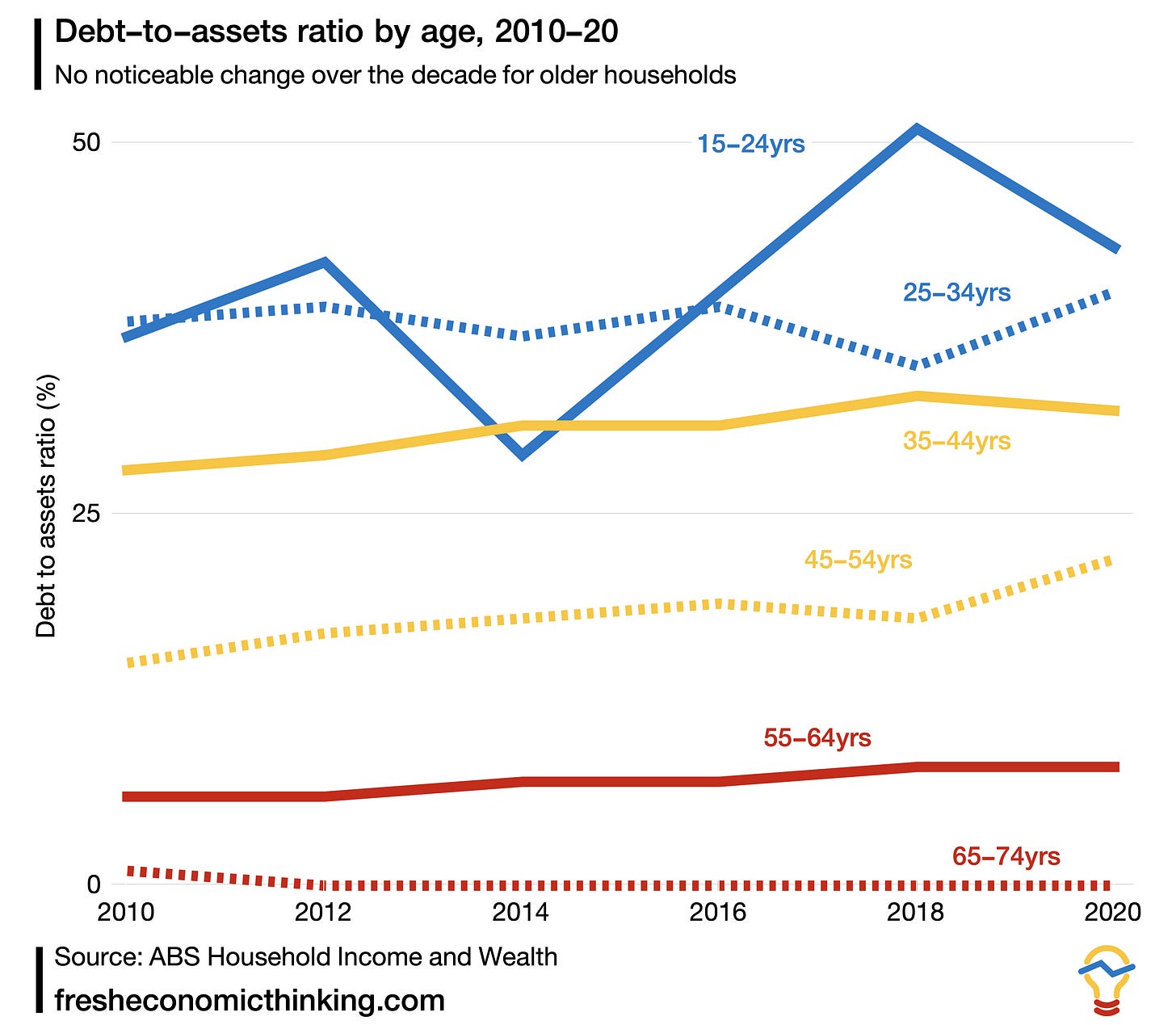

We need to use some indirect metrics here, and the most useful is the median debt-to-asset ratio for those aged 65-74 in the ABS Household Income and Wealth, Table 3.5. What we notice is that, despite this rise in the number of households with debt at that age, the median debt-to-asset ratio is… zero. It was near enough to zero in 2009-10. And still, zero in 2019-20, as seen below.

Debt to income? Well, that’s the same. A flat line at zero for those aged 65-74.

Much of that is because superannuation, after preservation age, can be withdrawn as a lump sum. If you have a mortgage at age 60, you can retire and take your super and repay the mortgage with it. It’s an asset swap that doesn’t change your net balance sheet position.

Many do this.

The majority of superannuation payouts now come in the form of lump sum withdrawals. It was about fifty-fifty up until 2020, with $10 billion of pension payments from super funds and $10 billion of lumpsum withdrawals per quarter. Now, lump sums are about 30% more (see Chart 3 here).

And what do people do with those lump sums? They mostly repay mortgages or buy more housing!

An ABS survey of over 8,000 people about their retirement provides an estimate that there would be in total about 490,000 retired people in 2020-21 who got a lump sum payment from their superannuation and used it to repay a mortgage, renovate, or buy a new home (see ABS Retirement and Retirement Intentions, Australia, Table 8).

The point is that the use of superannuation to buy housing is already common. It just happens after many years of sustaining both a mortgage debt and a superannuation asset, where it could instead be used up front as well.

The question should be, why wouldn’t a retiree pillage their super to pay for their house? A paid-off house is the best asset to have in retirement. It’s not pillaging. It’s just an asset swap.

Longer lives

A second fact, and one that will be a topic for future FET articles, is that people are starting work later in life and finishing work later in life. But we too often ignore this and compare fixed age cohorts over time.

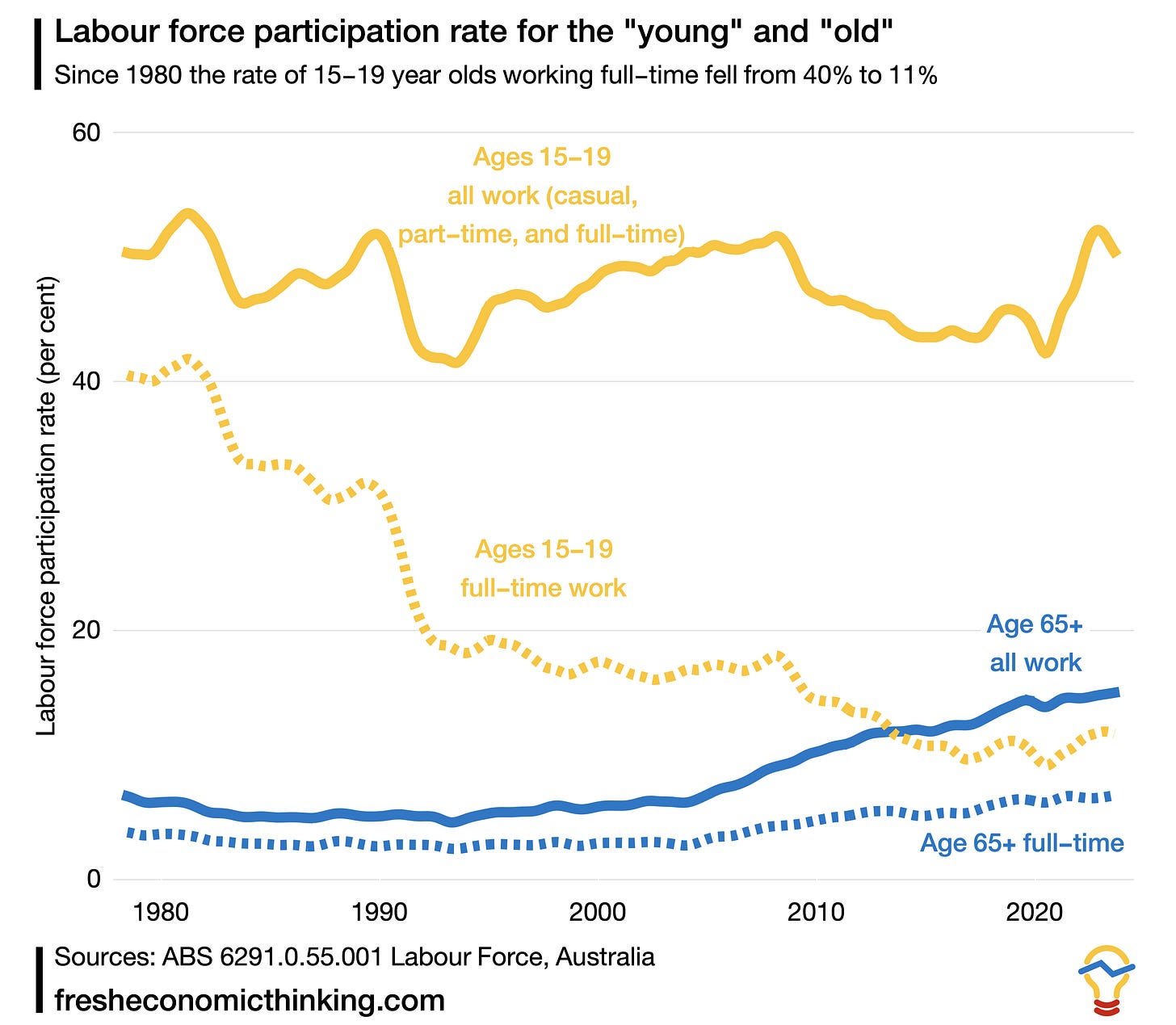

Take a look at these charts.

The first shows the labour force participation rate of the young and old (ages 15-19 and 65+). The big trend is the continued decline in full-time work for the young, and the rise in all types of work for the old. It might not look like much, but in 2000 only 3% of over 65s worked full time and now it’s nearly 7%. More than double. For all work, participation of over 65s is up from 6% to 15% since 2000, so about 2.5x more workers in that age group.

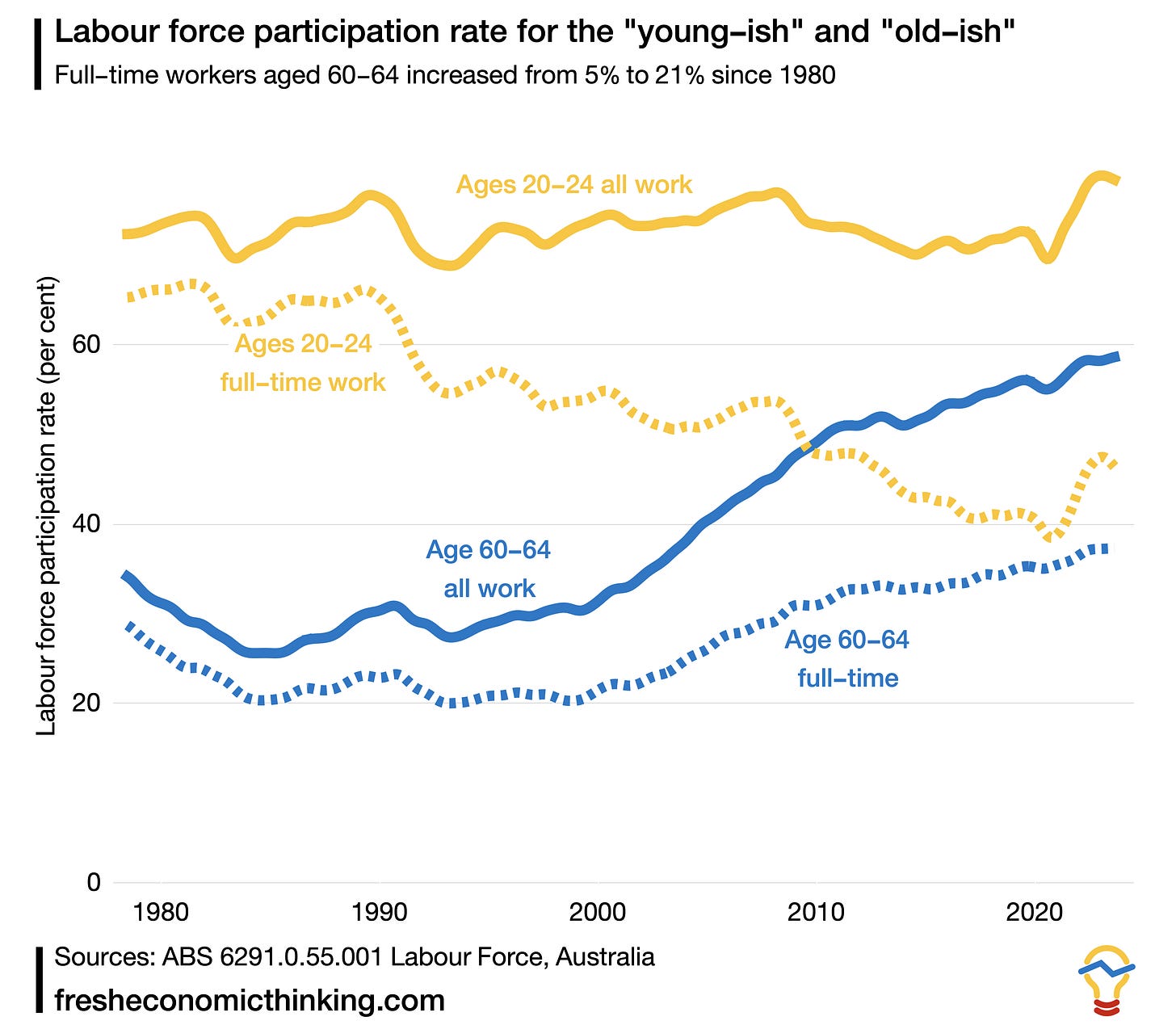

In the slightly older young, and slightly young old, we see similar trends. Even at ages 20-24, there is a major decline in full-time work, while in ages 60-64, there is a major rise in full-time and any other work.

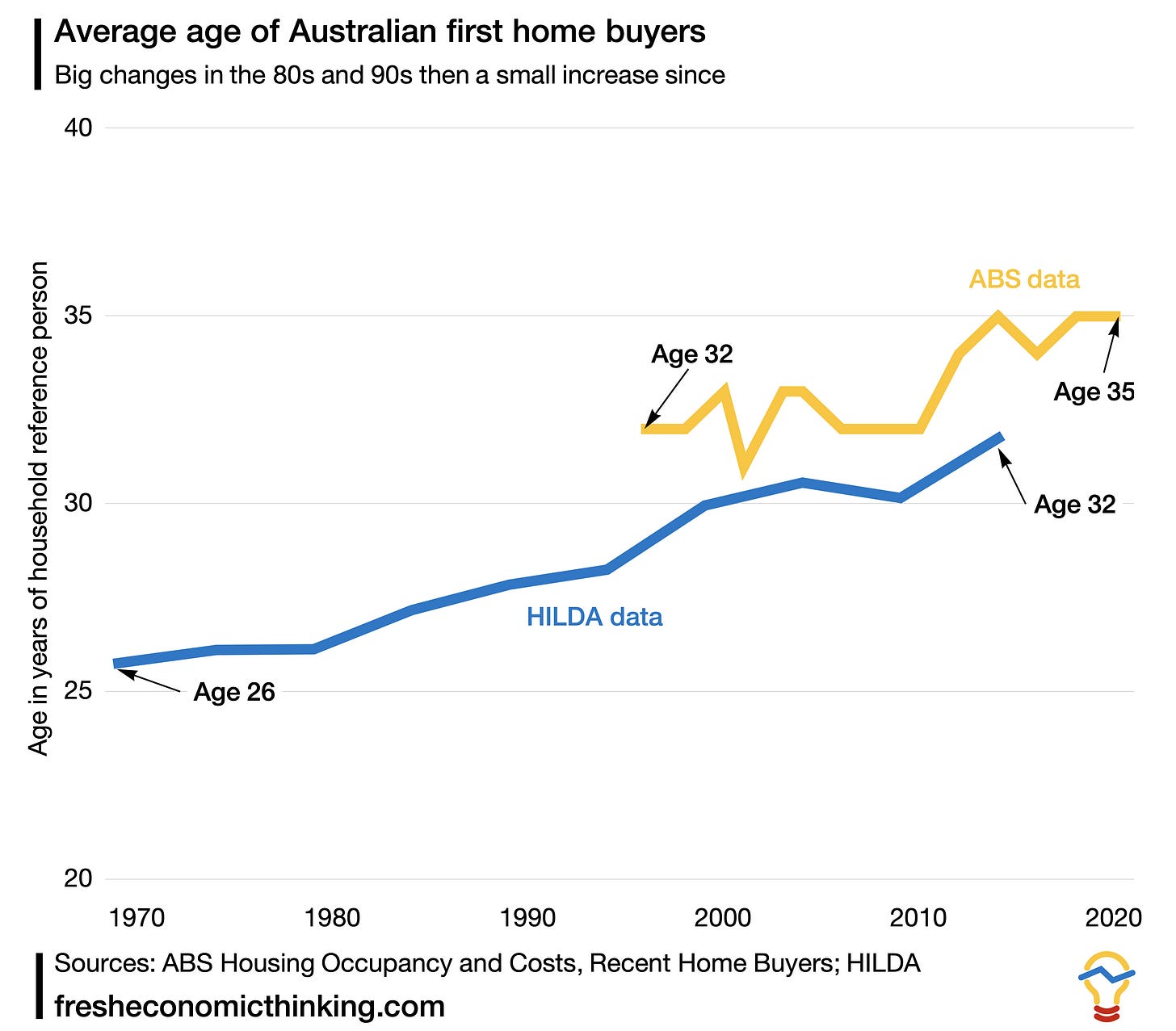

Being age 60 with a mortgage is just not comparable to what it used to be because of the much higher likelihood of continuing to work. The age of first home buying is increasing too. Life is stretching out.

Super for housing would boost prices

If everybody was told they have one year to use their super to buy a house then there would be a major (albeit temporary) price effect.

But people won’t have one year. There will be time for the market to adjust.

Just like when Elon Musk sells his Tesla stock he doesn’t do it all in one day, as it reduces prices, spreading out home buying, with super or any other source of finance, will dampen price effects as well.

Any price effect can be further limited by allowing superannuation to be spent on non-housing items too. Because it provides more opportunities for households to spend in other ways, this takes the pressure off housing alone.

In any case, just because people can “afford” a house, doesn’t mean they will buy it if it’s a bad investment. This is true in any asset market. Although it feels like nothing will stop the housing market, there are limits on how high housing asset prices can go. Investors aren’t continuing to snap up homes in many cities today because they don’t seem like a great investment at the high prices given the alternative investment options in the market.

We also often forget that superannuation is already used to buy housing, both directly and indirectly.

Self-managed super funds often directly buy housing. About $200 billion of the $900 billion in total self-managed super fund assets are in property, and I suspect that this is predominantly residential real estate (see ABS National Accounts, Finance and Wealth, Table 19). At the mean capital city housing value of $1 million per dwellings, we have up to 200,000 dwellings owned by self-managed super funds already, though how many depends on the proportion of non-residential property. If half the property is residential, then we are talking about 100,000 homes already bought by super funds.

Then there are the build-to-rent projects coming on board. Superannuation funds are active investors here. You might argue that this increases the rate of new housing development, but this would also be true for allowing people to spend their super buying a new house or an apartment to live in. If that’s the argument, then allow super for only new housing.

In sum, the two big arguments against using superannuation for housing aren’t the big deals they can appear to be at first glance. A home is the best asset to own in retirement and super is already used to buy housing.

In fact, it is completely strange to watch this debate unfold when places like Singapore prioritise using compulsory savings to buy your own home before investing money elsewhere. Yet in Australia, superannuation can only be used to buy someone else’s home.

If you want some straight facts, I suggest this report of mine that looks at the cost of the superannuation system and debunks the false economic mythology of super. If you want to see through some of the financial trickery of superannuation, I suggest this article.

This is data requested by SMH for this article and reproduced here.

"If you have a mortgage at age 60, you can retire and take your super and repay the mortgage with it. It’s an asset swap that doesn’t change your net balance sheet position."

Why is this only allowed at 60? Why not earlier? Most analyses focus on younger people and assume they have very little in their Super accounts. But what if you are in your early 40s and due to some good decision making now have more than enough, for a home and for retirement, and it is locked away?

Excellent piece Cameron!

Getting closer.

Best regards,

Simon Jones