Supply and demand: The NESTED nature of trading dimensions (Part III)

When economists talk about marginal costs do they know which margin? Let's think more clearly about ALL the margins.

In Part I of this Supply and Demand Series, I explained with a clean example of supermarket checkout queues the underlying logic of supply and demand in a market. Housing is a market where trade-offs must be made, so supply and demand must apply.

I explained how supply and demand are tools for helping understand the concept of a market equilibrium, noting that this is the imaginary point where there are no longer mutually beneficial trades to be made. The idea of a supply curve was shown to exist only as the demand curve of the current owners of the thing that can be traded.

In Part II, I dug further by explaining the importance of getting right the dimensions across which trades are made, and the source of benefits from trade. In housing, we can trade one location for another. We can trade up and down the quality spectrum. We can trade for more or less dwelling space. Across every dimension—of quantity, size, quality, and location, and more—there are trade-offs being made, and that means a supply and demand.

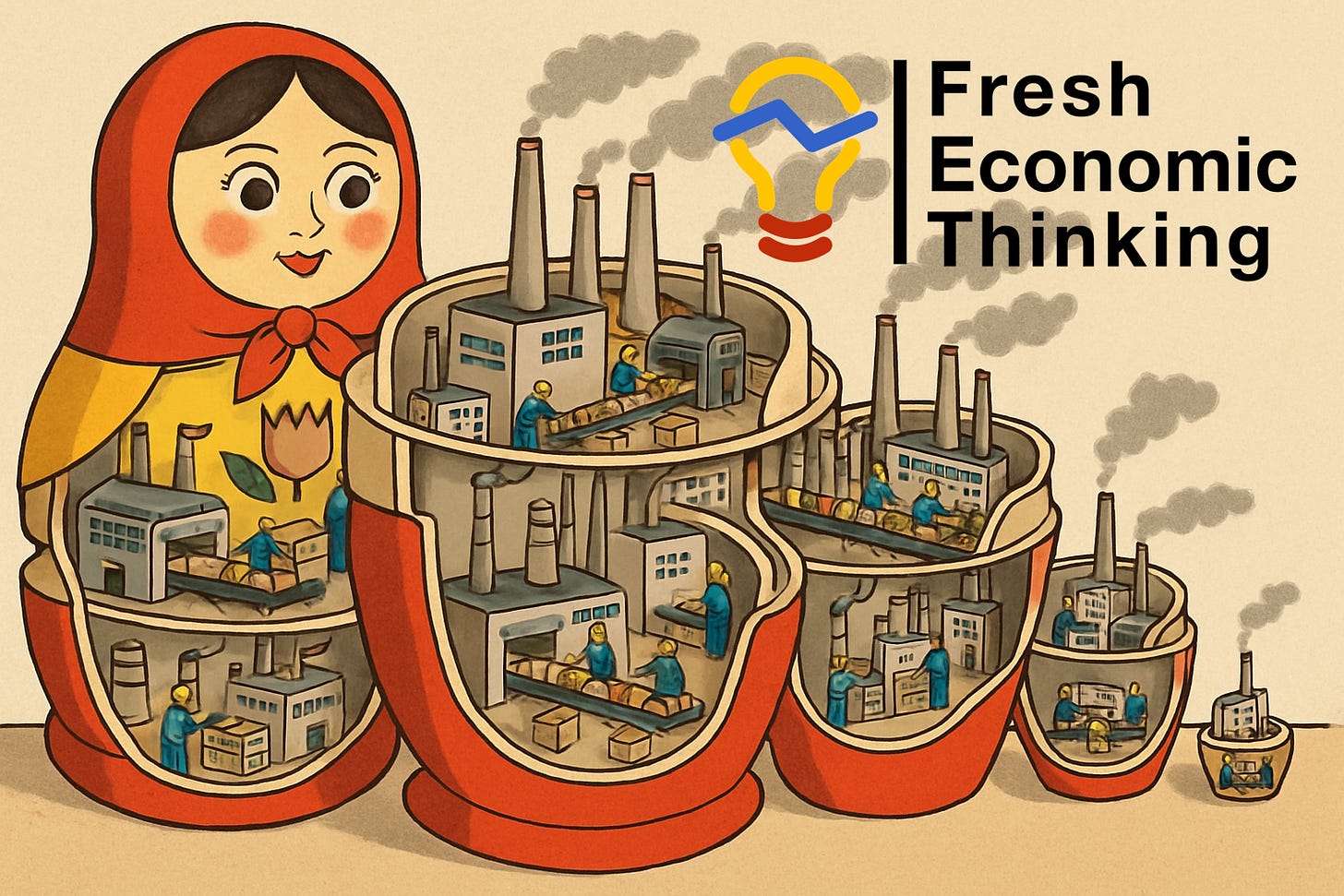

Here, in Part III, I explain the nested “Russian Doll” nature of margins across which trade can occur in each dimension. Yes, there are many trading dimensions, and within each, there are many margins.

What do economists mean by marginal?

In Part I, we showed how trades take place whenever the benefit to a buyer exceeds the benefit given up by a seller. The last potential seller and buyer who can profitably trade are the marginal buyer and seller. They are at the edge. The margin.

In our checkout example, when one queue is 5 people long, and the other is seven long, the seventh person is the marginal buyer of the 6th position in the shorter queue. People further up the queue have no reason to swap.

But it is also true that for the marginal buyer and seller, the last item they trade is the marginal one. They may trade many items with each other for mutual benefit until the last item they trade.

So yes, the trade of a single person from one queue to another is the marginal person, but within that person’s groceries, they have marginal items too.

Economists call this idea the intensive and extensive margins. The extensive margin is the decision whether to swap a queue, and the intensive margin is how many items you buy within your queue position.

What is marginal cost?

Remember from Part II that the price at which a trading equilibrium occurs is where the benefit given up for the last thing sold is just less than the benefit of the buyer for the last thing bought. The price is a measure of that benefit. Or, in the lingo, supply (benefit given up) is close to equal to demand (benefit received).

This is true for the last buyer (extensive margin) and the last item from that buyer (intensive margin).

Here’s where the rabbit goes into the hat in the economic theory that you might have learnt at university, which leads to enormous confusion in general, but especially around what the price of land should be (heard of the “zoning tax”?).