Since families share economic resources, does it matter if men earn more than women, or vice-versa?

Looking at the spending side of the household ledger, not just the income side, changes how we analyse the issue

The highest paid models are all women, who make 10x more than men1

The most likely person to die at their workplace is a man, who is 10x more likely2

Men pay more tax than women and receive less income support3

Women aged 20 and under earn more per hour than men in Australia, and women aged under 30 earn more than men in the UK4

Women are now more likely to attend and graduate university than men5

These are not disputed facts. But they help paint a more complete picture of the issue we now call the gender pay gap. I of course agree that men and women should be paid the same amount for the same job. But in the over a quarter of a century I have been working, I’m yet to experience a workplace that hasn’t paid men and women the same for the same job.

This is a good thing.

The Australia Institute recently published a report on the gender pay gap. I think it shows how much progress we made in the late 20th century towards gender pay equality and how little left there is to do. It’s been a great social improvement.

What is missing in that report, and indeed most economic analysis of the gender pay gap, is that men and women live in places called households. Usually they live there with other men, women, and children they call families, and these households and families pool their economic resources.

A man in a household with three women, say a wife and two daughters, could earn 100% of the income. It is just as valid to look at the spending side of the ledger, after resources have been pooled, as it is the income side, when judging the fairness of financial arrangements. In this scenario, each woman in the household would be spending 25% of a man’s income (and vice-versa if the gender roles are reversed) if spending choices were equally divided.

Every daughter spends her father’s money. So too does every son spend his mother’s. That’s the nature of pooled resources.

I wonder if we instead looked at households from the spending side, would men have a spending pay gap, and would that be something we as a society should remedy?

It is certainly true in my household that although I earn more than my wife she is in charge of most of the discretionary spending.

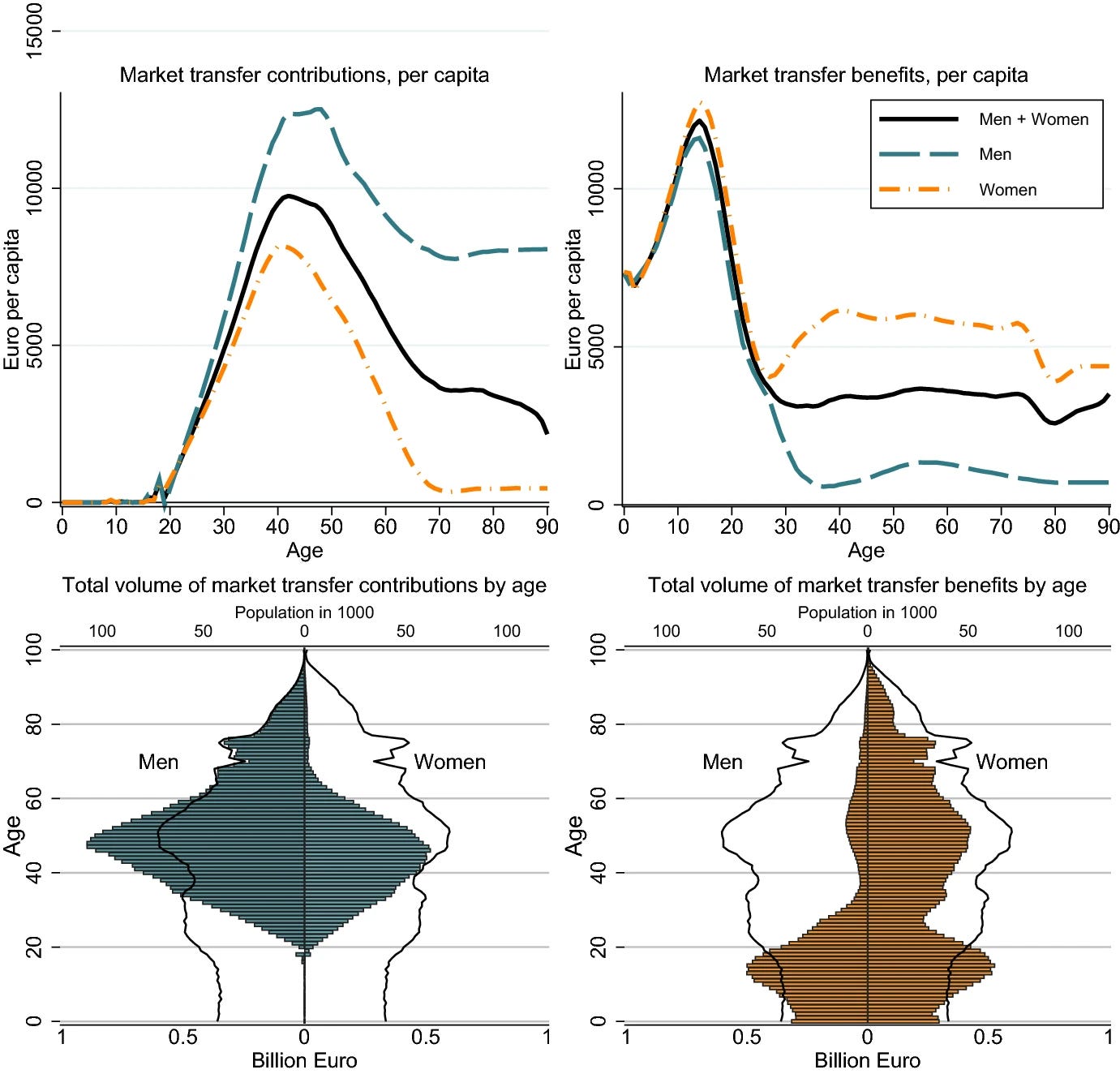

Last year, research on this exact question was published using detailed Austrian household income, spending and time-use data. That analysis looked at two types of intra-household transfers—priced goods in terms of money or goods and services (market transfers) and home production in terms of doing things for others like childcare, cooking, home repairs, and the like (non-market transfers).

The researchers estimated that women are recipients of over 5,000 euros per year of market transfers during their adult lives, predominantly from men who transfer about 10,000 euros per year to others in their household.

For non-market transfers, women were the net contributors on average, predominantly during the stage of life when they had young children.

Due to their higher income, men provide 71 per cent of the private market transfers. By contrast, women provide 74 per cent of the non-market transfers. Men share their higher income with their partner even after children have left the joint household, while women continue providing non-market transfers in form of household work.

They find it is also true in retirement that men continue to transfer the income to women to spend, which is relevant to Australia’s current debates about retirement incomes and superannuation. Of course, this is on average, and there are going to be many cases where this average is not representative. This is why I am such a big supporter of a retirement income system that pools resources across the nation, like the age pension, which can support single women (or men) or others in older age who cannot benefit from pooled resources from their family.

In fact, Paul Keating, former Prime Minister and father of the superannuation system explained a few years back how it doesn’t do the resource pooling functions it should to help, for example, older women.

Under the scheme, the "national family" would wrap its arms around the elderly to guarantee them an income, healthcare and accommodation.

In general, I think treating intra-household transfers with such a degree of economic precision can be fraught and can often hide further assumptions. The results of this study are probably not a surprise to anyone, so I’m not too concerned with nitty-gritty questions about things like defining a clear boundary between what is, and is not, a non-market transfer. One could go on about whether looking after your own children is work or leisure, and the same goes for gardening and other productive household hobbies.6

But doing this exercise helps us to look beyond the formal economy and incorporate the real and important economics of households, something that we should all care about. Yet talking about the financial reality of resource-pooling families seems unpopular when it comes to gender issues, be it pay scales or retirement incomes. This is despite the fact that resource-pooling is a built-in assumption of our welfare system, where cohabiting is enough for a couple to be deemed as pooling financial resources and hence no longer in need of welfare.

We should celebrate the social changes that have radically increased the possibilities for work, study, and fulfilment for women globally over the past half-century. We should be very aware of what success on this front means and be able to recognise when we get there. And we should be honest that families that pool resources are a real part of our economic and institutional structures.

https://fortune.com/2015/07/15/male-models-pay/

https://www.forbes.com/sites/chuckdevore/2018/12/19/fatal-employment-men-10-times-more-likely-than-women-to-be-killed-at-work/?sh=481689152e83

http://www.roiw.org/2016/n3/7.pdf

https://australiainstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Centre-for-Future-Work-Gender-Pay-Gap-WEB.pdf and https://www.theguardian.com/money/2015/aug/29/women-in-20s-earn-more-men-same-age-study-finds

https://theconversation.com/yes-women-outnumber-men-at-university-but-they-still-earn-less-after-they-leave-142714 and https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/11/08/whats-behind-the-growing-gap-between-men-and-women-in-college-completion/

I really should go on about this one day. We have in mind a weird idea that work is somehow fulfilling and simulating, but also a thing we dislike and only do for money. Also, why is it that some tasks are done as both hobbies and jobs? How can that be? This question of what is work and what is leisure is rarely given the consideration it deserves.

While I agree the “gender pay gap” is misrepresented by averaging across the entire workforce, I think your argument is specious because a substantial fraction of people are not operating in a “household” for a substantial fraction of their lives (and quite frankly it shouldn't matter, nobody is making salary decisions based on whether or not they're in a "household").

Typical (first) marriage age is about 30.

Something like 20% of households are not couples.

Something like 50% of marriages end in divorce.

And while averaging across the whole workforce does make the gender pay gap looks worse than it actually is, it also raises the question of why are low-paying jobs dominated by women, and why even in those industries, are the vast majority of higher-paying roles held by men.

For a personal anecdote, a while back ago my wife received a significant (over $25k) pay rise as a result of a salary review, to bring her salary in-line with the other - all male - members of her team (all of whom received very small, barely-inflation bumps), along with a once-off bonus intended to be back-pay for previous years. She is an Electrical Engineer in her 40s. The (department wide) salary review was instituted by the new, female, department head.

This was certainly not the first time in her ~20 year career a non-trivial pay discrepancy had existed between her and her male peers, but it _was_ the first time it was pro-actively addressed.

I do think that much of the real “gender pay gap” (ie: controlling for similar jobs) would be fixed by legislating wage transparency (ie: force employers to publish job titles and salary ranges, along with anonymised data of what they’re actually paying). The relative unwillingness of women to negotiate salary is well documented.

On a similar topic, I’d like to see some research done on how much of the retail market is geared towards women’s spending which could shed some light on the informal economy / discretionary spending you are talking about.

Anecdotally, when I walk around a Westfield, it seems like maybe 8/10 shops are expressly intended for women.

I personally spend almost nothing in my household except for food, public transport and the occasional bottle of whisky. My wife however has every dollar I’ll ever earn for the rest of my life already allocated 🤣