Property taxes reduce housing asset prices but don't make housing cheaper

Comparing home prices across cities with different property tax regimes is tricky

Low housing asset prices and low price-to-income ratios in many 'lightly regulated’ cities in the United States, such as Houston, Texas, are often cited as evidence of how tight zoning regulations increase home prices.

There are two major conceptual problems with such comparisons.

First, the price of an asset, like a home, is determined by its net cash flow. If planning regulations change the price of homes, they must do so via the price of renting, with the effect passing through to lower cashflows for the property owner, and hence lower asset prices.

Second, it is too often ignored that different property tax regimes affect the net cashflows to property owners, and hence have an enormous effect on housing asset prices. Others have noticed that this second point is often overlooked.

Here, I want to show how big this price effect can be by calculating the price reduction that would occur on a home I own in Brisbane, Australia if the property tax regime of Houston was adopted.

My home in Brisbane is worth about $1.25 million. I pay about $2,600 per year in council rates, which are a type of property tax. That’s 0.2% per year of the property value.1

The market rent for my home would be about $700 per week, say $36,000 per year, which is $33,400 after paying annual property taxes.

In Brisbane, there are stamp duties, or transaction taxes, which are 5.75% of the property value above $1 million plus $38,025, or $52,400 in total in this case.

From an ‘after-tax’ perspective, the purchaser of my home in Brisbane is paying $1,302,400 to get ownership of the property ($1.25 million to the seller and $52,400 to the state) and receives $33,400 in rental benefits per year, for an ‘after-property-taxes’ yield of 2.56%.

Advertisement – Fat Tail Investment Research

Fresh Economic Thinking is reader-supported (thank you). I will also post advertisements from time to time.

Fat Tail Investment Research is an Aussie outfit that publishes research on a range of investment options. The people there have been readers and supporters of my work for many years.

Sign up for free using this link for their investment insights about stocks that historically pay a consistent income AND could deliver capital growth.

Property tax rates in Texas are typically levied at 1.9% of the property's market value. That’s nearly ten times higher than my property taxes in Brisbane. Property taxes are similarly high in other places, like Nebraska.

So, how much cheaper would my Brisbane property be if we adopted a Texas property system and removed stamp duty while increasing property taxes from 0.2% to 1.9%?

The answer is that my home would have a 35.5% lower market price.

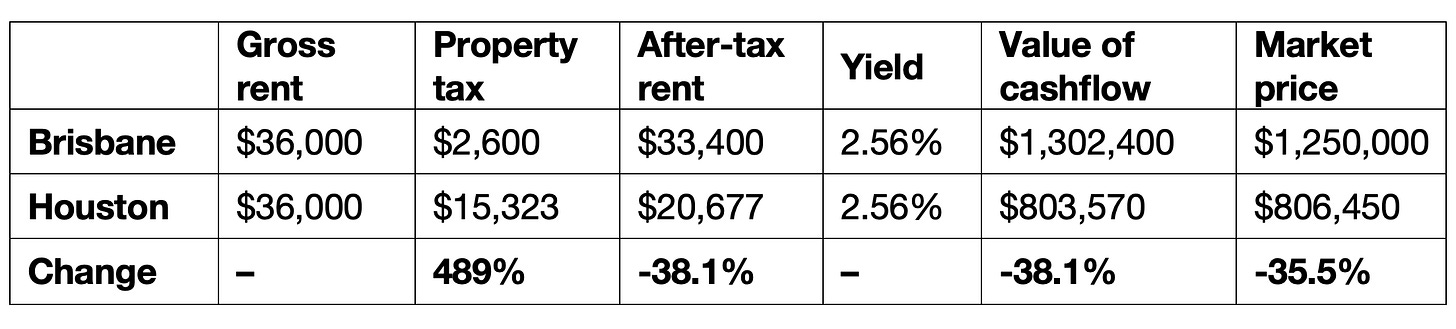

The table below shows the logic.

We can start examining this table from the right-hand side. Because there would be no stamp duty in this new ‘Houston’ property tax regime, the value of the cash flow would be the same as the market price. Under the current ‘Brisbane’ property tax regime, the value of the cash flow (the amount you are willing to pay) is paid to the seller and to the state, reducing the market price paid to the property seller.

But that cash flow will be lower. At a 1.9% annual tax, a market price of $806,450 creates a tax obligation of $15,323, which is a 489% increase on current property taxes.

This reduces the after-tax rent by 38.1%, reducing the net cash flow from $33,400 to $20,677. This cash flow is the same 2.56% ‘after-property-taxes’ yield on the $806,450 market price.2

In both situations, you get the same yield on the money spent to get ownership of the asset and the same gross rent. The only difference is the property tax regime.

But this change in taxes doesn’t make the home cheaper, even though the market price and price-to-income ratio are both more than a third lower.

The house still rents for $36,000 per year. It is just that owning the property is less valuable because the asset comes bound to a higher tax liability, which reduces its value.

Property taxes in Queensland and most of Australia are levied on land value, not total property value.

I am also ignoring that these higher property taxes will mean lower capital gains too, and hence buyers in high-property-tax areas will require a higher yield, further depressing the asset price and making comparisons between housing asset prices in high-property-tax and low-property-tax areas even more difficult.

This all makes complete sense. Thanks for laying it out so clearly.

For anyone unconvinced, this is further reason to focus analysis of housing affordability exclusively on rents.

Since asset prices are buffetted around by interest rates and expectations and are skewed across jurisidictions by tax rates, the only reliable way to conduct like-for-like comparisons or comparisons through time is to use rental prices for dwellings of a consistent quality.

Thanks Cam. I agree the tax regime matters when comparing house prices across jurisdictions. For instance, Glaeser and Gyourko (2018) 'The Economic Implications of Housing Supply' incorrectly identified Houston as being a city where prices were below the 'minimum profitable production cost' (ie, a city in decline), when it's the classic fast growing city with responsive housing supply. That's because Texas makes above average use of land taxes to fund public works, so its house prices would've seemed too low compared to their default benchmarks.

But I wouldn't apply Texas's property tax rate to a Brisbane priced home. Their house prices are vastly less, so they pay less tax than your example implies. Also, maybe half of those taxes pay for schools and their income tax rates are correspondingly lower. Eg an example I have from 2018 is a new build in a Houston municipal utility district valued at $185k USD with annual taxes of $5.4k, of which $2.4k are for the schooling district. Given you won't pay for schools through your property tax, the $3k non-school property taxes are on par with what you pay.

If houses were trebled in price, all else equal, it's more reasonable to presume their tax rates would reduce to one third to maintain govt revenues. Also, your net income would be higher with Texas taxes because your income is not used to pay for schools serves your broader point thought: it's hard to compare house values across different states and countries.

Also in some states they cap use a much lower "assessed value" basis to apply the tax rate to, which is based on a price circa 1990 that increases only at something near the rate of general inflation (eg 2% in California, or 3% in Oregon). The market value and 'assessed value' can be very different. So US states generally wouldn't ever apply a 1.9% tax to an overpriced house such as in Brisbane, so it's not the right comparison. Perhaps if you reduced the value of your home to 1990 prices and then applied the 1.9% tax you might get it closer to the annual property taxes paid.