No one knows how to handle housing in the CPI: Singapore edition

Nearly 90% are homeowners but nearly 20% of the CPI is housing rents

One of my interests is how Singapore took homeownership from about 25% at the time of independence in 1965, to over 90% three decades later in the mid-1990s.

As usual, when I start looking at a topic I get end up digging into way too many details.

This article is about one little thing I recently noticed that struck me as quite strange, and it has to do with the problem of housing in measures of consumer prices.

Around 90% of all Singapore households are homeowners (about 80% in the HDB public homeownership scheme). But the imputed rent component of Singapore’s consumer price index (CPI) is roughly 17.5% of the total basket of goods. When CPI is calculated based on the spending patterns of only the lowest 20% of households by income, around 29% of the CPI basket is imputed rent.

Statistics Singapore notes how strange it is to put an estimate of the rent a homeowner would pay themselves as a major component of CPI since homeownership is so high in the country and there are various housing subsidies that affect prices in accommodation subcomponents.

The Owner-Occupied Accommodation (OOA) cost in CPI comprises rentals that are imputed for owner-occupied homes. Imputed rentals on OOA have no impact on the cash expenditure of owner-occupied households. In addition, under “housing maintenance & repairs”, the rebates for service & conservancy charges (S&CC) which are given to households living in HDB flats in different periods of the year result in some volatility in the monthly CPI. For “All Items less imputed rentals on owner-occupied accommodation”, actual rentals paid on rented units are still included in the measure.

Removing the made-up imputed rent component of the CPI at times makes a huge difference when trying to understand price and cost-of-living changes.

In this 2017 article, which provides the below table you can see that removing imputed rents turns the CPI growth in 2015 from -0.5% to +0.1%. In 2016 from -0.5% to +0.3%. In the second half of 2016 it changes from -0.2% to +0.7%.

What is happening here is that falling rents in the market sector during the 2010s are being scaled up into the CPI, lowering the overall measure. When market rents rise, the opposite will happen. And in both cases, none of it reflects any actual spending that takes place.

Weird.

Knowing this important difference between headling inflation and CPI net of imputed rentals helps to understand how inflation affects the household spending of 90% of Singaporeans.

I noted in a previous article how the way housing is treated very differently in CPI in different countries, which has implications today if you want to understand the relationship between, say, the rental market and measured inflation.

In Australia, we don’t include imputed rents in our CPI at all. So our booming rental market will have a much smaller effect on the measured CPI than in places like Singapore or the United States, where imputed rents make up 19% and 24% of the consumer basket respectively.

A final weird piece of the puzzle is how large the US imputed rents are in CPI compared to Singapore. The Singapore CPI imputes rents for 90% of households, who, as a rule of thumb, would typically spend 20% of their income on renting. Multiplying that 20% by the 90% of owner households gets an expected weight of 18%, close to the actual weight of 19%.

But in the United States, the weight of imputed rent in the CPI is 24% for the 65% of owner-occupiers. But if 65% would otherwise spend 20% of their income on rent, then the basket weighting should be much closer to 13% for imputed rents (0.65 x 20 = 13%). It is nearly double that.

But for the 35% of renter households in the United States, we get a sensible 7.4% weighting for rent in the CPI, which fits this rule of thumb of 20% of income spent on rents (0.35 x 20 = 7%).

I have no idea why the imputed rents are so high in the United States CPI. But for me this all points to the fact that we have no good way to factor in housing in the CPI.

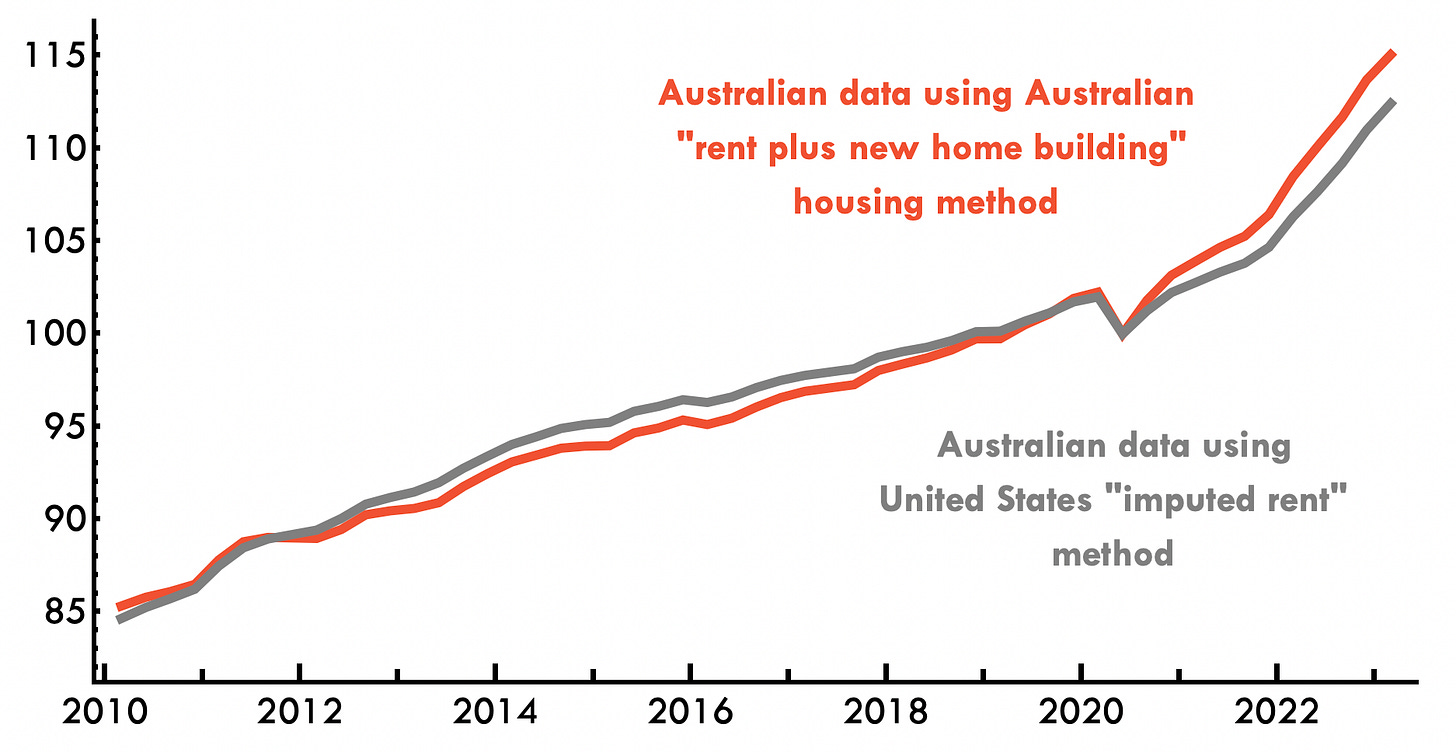

In the below chart I have scaled up the CPI rent in Australia to 32% of the basket, imitating the US method of including this much rent and imputed rent in their CPI, and compared to the Australian method. Notice that because rents have been a drag on inflation for the past seven years1 that Australia’s method estimates a higher inflation rate than the United States imputed rent method.

But this doesn’t mean that Australia’s inflation should have been higher. It is just a statistical artefact that needs to be acknowledged by users of the CPI statistics.

To further indulge my thinking a little, imagine if we treated motor vehicle transport like we treated housing. For car owners, instead of including the prices of things needed to drive themselves in their own cars, like the price of petrol, maintenance, and so forth, we imputed the price of taking a taxi instead and used that to measure the change in the price of driving.

Or what if 100% of households were homeowners? What price would we use then to measure the cost of housing? We couldn’t use rental prices, or impute them, since there would be no renters. Construction costs could be used, like in Australia’s CPI method. What about housing asset prices?

I don’t have a clear answer for how to handle housing in the CPI. I don’t think there is a “right” answer. But it is always worth keeping in mind that the economic measurements we see don’t always correspond well to the more vague economic concepts we have in our heads.

Interesting stuff Cameron.

It preempts the Q as to how much imputed rents in Aust have affected GDP. If GDP increases as a result of increased imputed rents should we be patting ourselves on the back for dodging a recesssion?

As it is ,history suggests measuring GDP is a highly politicised activity..... not a straightforward process by a few beancounters......... if Jacob Assa's tract "The Financialisation of GDP" is anything to go by. Does the financial sector add as much to GDP as currently measured, or has the way we measure GDP changed over the years, so that its products which were once all intermediate goods and thus eliminated in national income accounts, to a situation now where they produce lots of final goods and are helping us avoid two quarters of -ve growth which otherwise might suggest a recession..... or so the commetariat tell us

It depends in part on what you want the Inflation measure for. The best measure to use if BoA has and inflation target, might not be the best one for calculating changes in real income. Or real wages.