Make welfare better with a Universal Basic Income (UBI)

Call it what you want, but letting the tax system work rather than using cumbersome eligibility requirements for each welfare program is fair and efficient

Don’t forget to pick up a copy of The Great Housing Hijack. Upcoming in-person events:

Melbourne: 20th March, 12.20pm, John Cain Luncheon with Per Capita

Canberra: 21st of March, 6.30pm hosted by The Australia Institute

Paid FET subscribers get access to this post and article voiceovers on their podcast feed.

Universal welfare services are a good thing.

I like that we get to drive on public roads, kick a footy at the park, use a public library, and send our children to school, without having to jump through eligibility hoops to make sure our income is low enough to qualify.

After all, higher-income households can afford books, backyards, toll roads, and tuition, so it seems silly to just let these households use these services for free. Right?

One thing that is widely thought to be very bad is middle-class welfare.

But when middle-class welfare comes in a non-cash form we all love it, whether that form is schools, roads, hospitals, and other services. But cash? Nope. That’s a problem.

So our cash welfare system has evolved into a maze of hoop-jumping and arbitrary phase-outs of a huge range of different specific welfare programs to accommodate political whims.

Take a look at this guide and see if you understand the system.

And the closer we can inch towards universal cash welfare, which relies on the tax system to recover revenue rather than restrictive qualifying criteria and income-based phase-outs, the better that system will be for rewarding work and productive endeavours while saving billions in administrative costs.

Some cash welfare payments are already like this. And people love them.

Universality works

In New Zealand, the age pension (called NZ Super) is a universal basic income (UBI) for old people. It has no income or assets test for eligibility. Instead, age pensioners simply pay tax on their income if they work and earn above this UBI amount.

Australia’s age pension, in contrast, has an income and asset test that hits about 800,000 out of 2.6 million age pensioners and phases out the pension payment at 50c for every dollar earned. This is equivalent to an extra 50% tax rate on earnings, above and beyond any other income taxes. So if pensioners work they will lose 69c to 82.5c from every dollar earned!

Because people in New Zealand over 65 aren’t punished as much financially for working, more older people work in New Zealand (25%) than in Australia (15%). Sure, there is higher churn—meaning the same people both receive welfare and pay taxes—but churn is not a real economic concern or cost.

Churn is a made-up, and very Australian, marketing phrase used for political convenience. Churn is costless because it simply requires two instant and free electronic payments, but administrating systems to avoid it cost billions in manpower, resources, and much more in bad work incentives.1

Because of its great work incentives and efficiency, New Zealand’s over-65s UBI has even attracted the interest of the Institute of Public Affairs (IPA), which published a report about it and not only recommended copying this for pensioners, but for students as well. An ode to generous and broad welfare if ever I’ve seen one.

The relevant economic concept we should be discussing when it comes to welfare design is the Effective Marginal Tax Rate (EMTR). It is an income earner’s marginal tax rate plus the marginal rate at which you lose other income or benefits. So for age pensioners, their EMTR is 69-82.5%. Is it worth working and only keeping 17-30c out of every dollar? Not really.2

And that’s the problem with our aversion to middle-class welfare. In reality, it punishes work rather than incentivising it. And unfortunately, those high EMTRs hit a huge range of Australian households.

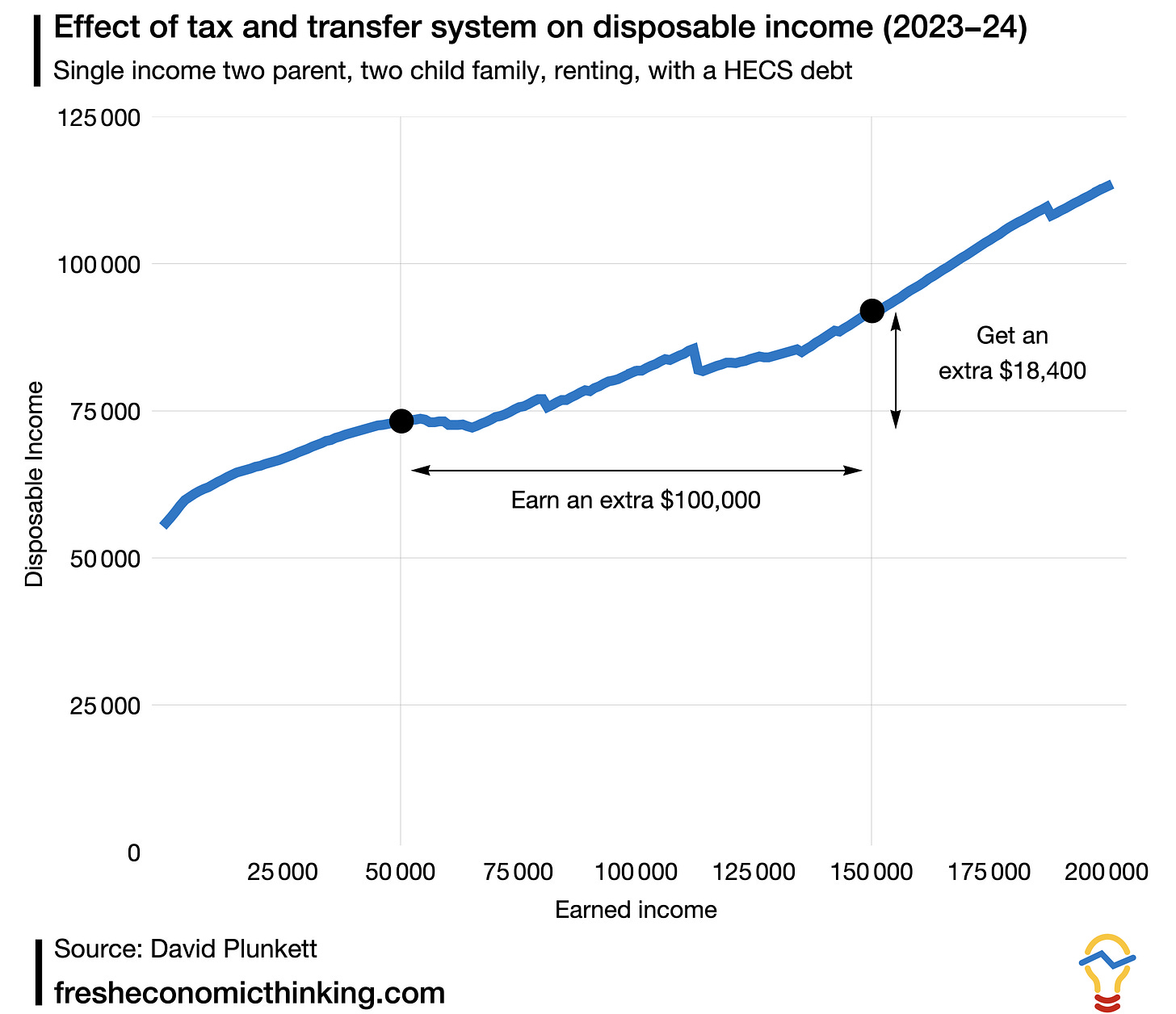

Consider the chart below (thanks to Dave Plunkett for the analysis here). It shows the situation of a single-income family that rents their home with two children and a HECS student loan debt.

The blue line shows their take-home disposable income, after the combined effect of welfare and taxes, given the private income earned which is along the x-axis.

So if the income earner in the household makes zero income, then the family gets about $55,000 in total welfare and hence that is their disposable income. If they earn $50,000 from a job, then they get about $73,000. So out of the $50,000 they earned, they only increased their income by $18,000, so the EMTR in this range is 66%—every dollar they earned only increased their disposable income by 34c.

But it gets worse! Much worse.

If they go and get a new job earning $150,000, which is an extra $100,000 of private income, they lose all their various family-related welfare payments, must repay HECS debts as well as pay tax, so their disposable income only rises by $18,400 to about $92,000.

They make $100,000 of extra income, but only increase their net take-home disposable income by $18,000. Across that whole income range, which is what most Australian households earn, there is an EMTR of 82%. They only keep 18c out of every extra dollar they earn.

The huge difference between the marginal income tax and the total EMTR is shown below. For most Australian families with incomes less than $150,000 per year, their EMTR is way above the income tax rate. If we care about work incentives, we must consider the tax and welfare systems together.

For me, these punishingly high EMTRs, especially for family households and age pensioner households, are a huge economic cost we could avoid by redesigning welfare to be more like a UBI.

Is UBI equivalent, or better?

It is worth noting that you can design a welfare and tax system that gets the same net outcome by either means-testing or by letting the income tax system do its thing.

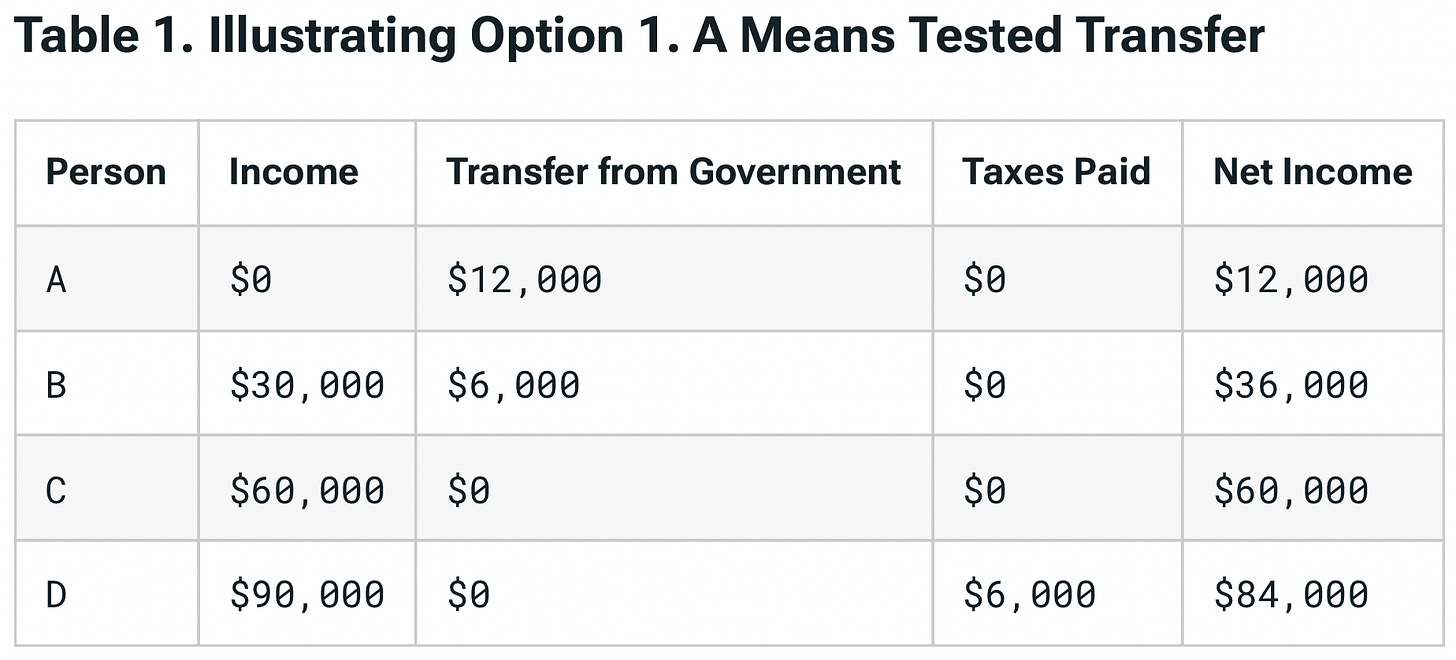

I’m going to borrow a nice clean example from the Tax Foundation to show that a UBI and a means-tested welfare program can be equivalent.

Here’s the case of the means-tested program. You get a $12,000 base rate of payment, but once you start earning income, you lose 20c of the payment per dollar of income. That’s the phase-out.

So if you earn $30,000 of private income, you lose $6,000 of the payment to have a net income of $36,000.

By the time you earn $60,000, you get no welfare payment.

But then, after $60,000, you pay a 20% marginal tax rate, then you get $84,000 of net income if earn $90,000.

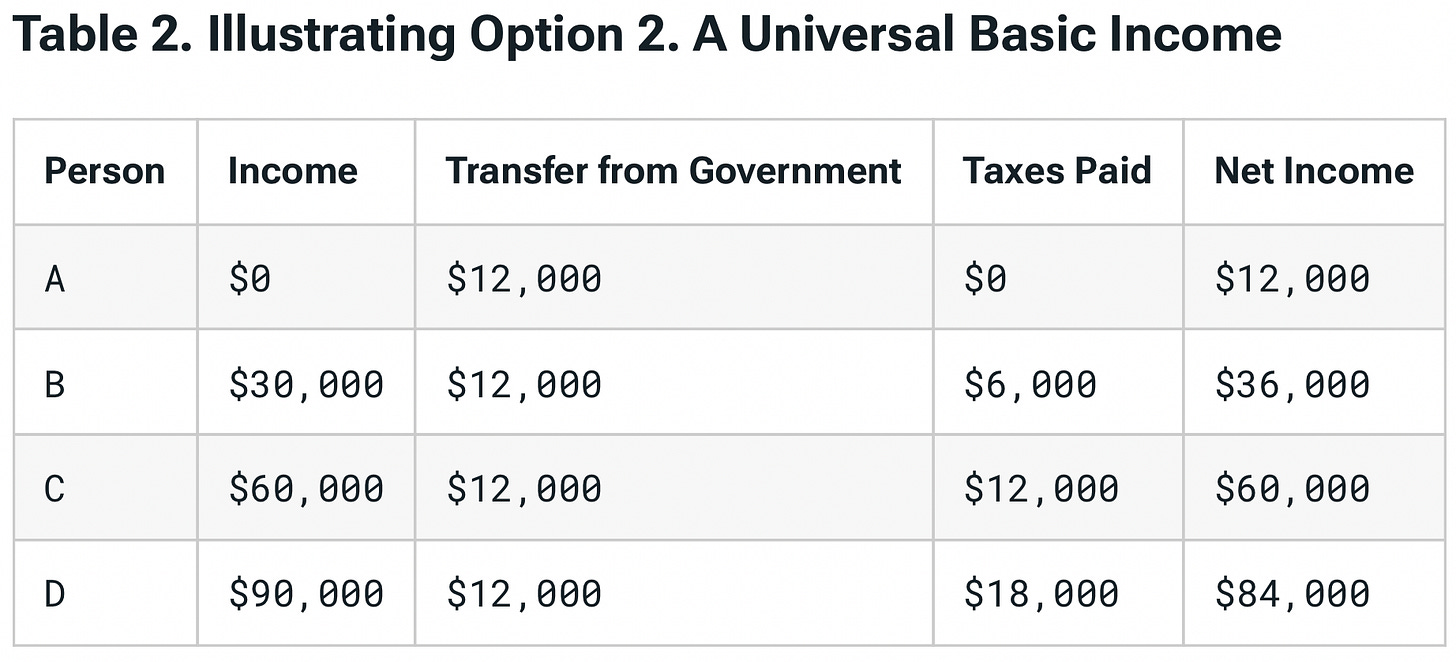

Because means-testing involves reporting income changes, checking in with welfare administrators, and dealing with over- and under-payment as circumstances change, you can make the same payment with no phase-out. Just give everyone $12,000. And instead, you can use the tax system to take back 20c for every dollar earned.

This situation is summarised in the below table.

Notice anything? The net income is the same for every amount of private income earned. The difference is in administration.

It is this equivalence that makes sense of calls for more universal welfare payment. Targeted welfare is just a more difficult administrative way to get the same outcome as universal welfare and a simple income tax system.

An indicative proposal

Most welfare payments fall into these categories

Old age

Unemployed

Families

Disabled

Within each category, Australia has multiple distinct welfare programs, with rent assistance sprinkled through as well.

A UBI could fix the bad work incentives with the age pension by copying New Zealand’s approach. I don’t see why that can’t also be extended to all working-age individuals as well, which covers off the unemployed category as well.

Families could get a smaller child-size UBI for each child and a high-needs UBI for disabled family members.

That’s it. All the categories are covered.

To recover more tax revenue to maintain a reasonable tax balance, the first marginal tax rate could start at something like 35c in the dollar from the first dollar earned for all individuals, then perhaps a higher 40c marginal rate at higher income levels.

Then let the system fly!

Of course, you don’t need to fully recover to cost of payments via income taxes alone, as other tax bases can be adjusted during a transition period towards universal welfare.

What do we get from this?

We would save billions in the administrative cost of the welfare system, which currently costs about $7 billion. These costs could easily be reduced by $4 to $5 billion per year. We would also have much more sensible labour force incentives across all household types, which could have enormous efficiency and output effects.

Concerns

The beauty of universal welfare is that it lets the tax system do the work rather than obsessing over non-issues of churn and middle-class welfare.

But surely it’s not that easy.

Unfortunately, it is that easy. The barriers are all political. We just don’t want simple, fair and universal welfare.

Consider the case of Poland. In 2016 it introduced its Family 500+ child payment scheme of 500 PLN per month (about USD $125, or 18% of Poland’s minimum full-time wage) for each child after your first, and for all children in low-income households. It was intended to stimulate fertility and was expanded to include all children in 2019.

It has been a huge success in terms of keeping children out of poverty and helping families, and it has buy-in now across the political spectrum. It is politically untouchable, despite failing to get its desired effect of boosting fertility.

A Polish-style child payment and a New Zealand-style age pension get you most of the way to a UBI. If their experiences are anything to go by, people will love it and it will be hard to reverse.

One concern is that some people will want a UBI cash welfare system to replace non-cash welfare like education, health and other public services. But these services will always have a place and I think a mix of public and private provision makes sense in many situations.

But I don’t see that happening in New Zealand or Poland to any serious degree.

I can already hear cries from the political left that “If the right-wing IPA likes it, there must be a catch!”

The issue for the “progressive” side of politics in Poland was that a child-UBI achieved directly much of the income security and workforce flexibility for families they were trying to achieve indirectly (as noted here).

For progressives and other PiS opponents, these programs’ popularity leave them with little room to maneuver, except to call for more investment in public institutions such as child care, schools, and hospitals. Barbara Nowacka, a politician who ran the campaign on social policy for a left-wing coalition in 2015, told me its message, which included promises to invest in kindergartens and encourage employers to offer women better job protection and flexible work, was admittedly “boring” in comparison. She would prefer to see the program’s budget—estimated by the labor ministry at 31 billion złoty in 2019 and 41 billion złoty in 2020—directed toward services such as warm meals in schools and school-based medical services, such as nurses and dentists. “But we know that this 500+ satisfies people,” she said. “Everyone believes that it is better to have money than trust the state.”

I think this quote also shows the weird debate. On the one hand, we don’t trust the state so want the cash. On the other, the cash relies directly on the state.

A UBI for children could replace income-tested child-care subsidies which only further add to punishing working parents. With cash, you can pay child-care, pay grandparents or friends, or even look after your own children.

One feminist professor noted the following about the success of Poland’s child UBI.

… Family 500+ recognizes the economic value of caregiving, an acknowledgment that, ironically, could give women more power within their households, even as it may discourage them from joining the formal labor market.

At the same time, it keeps conservatives happy because it

… reinforces traditional values that still resonate widely among the country’s conservative voters.

Another concern with universal welfare is that people live in units called families, or households, that pool resources. If each individual gets a UBI, this advantages larger households over smaller ones.

For example, if you have six children, all eight of you will get a UBI either at a child or adult rate, and you will have huge economies of scale advantages over eight single-person households getting the same adult rate UBI.

This is of course an issue for the welfare system to some degree, but so what? Should our tax and welfare system not incentivise people to live in economically sensible-sized households?

A final political concern could stem from the fact that Poland’s child UBI reduced the workforce participation of mothers. Some people might see this as a bad outcome. But of course, this can only be due to the choice better reflecting the desire of mothers. After all, they are punished less for working with a child benefit that doesn’t phase out when they earn money. This is consistent with findings that the program didn’t increase fertility but massively reduced poverty in family households.

As a final comment, fixing welfare with universal cash programs works for everyone, so traditional political dividing lines don’t make much sense anymore.

I’m wary that since the IPA supports an old-age UBI like New Zealand’s age pension, Australia’s progressives will find reasons to oppose it. One reason they could latch onto is the fact that because family households typically are in the upper half of the income distribution (because of dual incomes, working age, etc) UBI might be on balance an upward wealth distribution over certain income ranges when measuring by household rather than by individual.

But that’s politics I guess.

Once that political leap is made, universal systems like this become entrenched. They don’t become costs. They become investments, birth rights, and hard to unwind. They also make us forget our foolish obsession with churn.

It is the targeted and means-tested welfare programs that face the most political risk, yet they also come with the biggest economic costs because of administrative burdens and ridiculously high EMTRs.

I can’t seem to pin down the origins of the term “churn” but a few things stand out. First, if you search Google Scholar for “tax welfare churn” most results are from Australians and especially from think tanks and political groups, not economics journals. Second, back in 2005 Peter Whiteford measured this made-up thing and found Australia was the lowest tax churn out of any country studied.

In Australia, you can only work and earn below a certain income level to get the age pension before it phases out. You also must wait until age 67. Strangely, it is possible to get your superannuation at age 60, but only if you retire altogether. Superannuation encourages early retirement and less work, while the age pension design discourages all working later in life for those who rely on it.

Raises an interesting question of whether cheaper childcare (the current policy focus) is an inferior pursuit to just reducing the EMTRs and raising the payments for families with children of childcare age.

Although I also understand there's some sort of big literature on the benefits of early childhood education and some countries like France go down the path of making that free. So not sure how that plays out in those competing policy priorities

Put this on your twitter post but I thought I'd put it here. Might be clearer to explain with more space.

Wouldn't a UBI translate into, essentially, a wage subsidy for businesses ? Doesn't it effectively absolve business of its (admittedly shaky) social contract to pay liveable wages ?

Eg: someone is working a low-skill job on, say, $50k/yr and getting by. A $30k UBI comes in. Their employers fires them, then rehires them for $20k, which when added to the $30k UBI leaves them in a net unchanged position.

The employer, however, has saved $30k (simplistically) off their salary costs for every worker they can do this with.

(For the sake of argument ignore the legally questionable fire/rehire process.)