Hijacked housing debate trifecta

Three easy pieces on how we're being distracted from real affordability solutions.

Today, dear reader, you have won the housing policy trifecta.

The first of three pieces below is an extract from Cameron’s book The Great Housing Hijack which explains the symmetry of housing markets — a key feature of housing that encourages vested interests to hijack debates, and leads any attempt at consistent reasoning to appear out of tune with the public conversation.

For more about the book, see here:

In the second article, Cameron and Geoff Hanmer explain that despite widespread media and policy attention, construction productivity in Australia is not in trouble. Cameron has previously published deep dives into construction productivity concepts and measurement, explaining how productivity gains do not lower prices, but instead increase the development density that is most profitable.

Here are those articles:

In the third article, Tim Helm discusses the obsessive focus of many housing analysts on regulations on the built form of housing, and their single-minded pursuit of providing more zoned capacity for development even absent any theory of how this will make housing cheaper.

Tim and I have previously written about capacity measurement here:

We hope you enjoy this week’s reading.

1. Winners and losers

Excerpt from The Great Housing Hijack.

The reality is that, underneath this charade, every current home and every possible future housing development project is owned by someone — the landlord investor, the speculating land banker or the housing developer — and every economic gain for them is exactly equal to an extra cost for a new buyer or tenant. This “owning” side of the market is driven by their desire for investment incentives so as to maximise their economic gains from the property they own; they are not interested in minimising the prices paid by renters and first home buyers. To give a sense of the scale of these gains, the average Sydney home typically makes more income from rent and capital gains than the typical Sydney full-time worker earns.

I call this core economic feature of the housing market the symmetry of property markets. For every tenant who gets a lower rent, there is a landlord who loses an equal and opposite amount of investment income. For every first home buyer who takes advantage of a price decline to buy into the market, there is a seller who has mistimed the market and sold at the market bottom.

The return to normal operation of private property markets after the mid-century deviation is a story of declining home ownership and declining public housing options. But the symmetry of property markets means it is also the story of rising private landlords. The story of rising house prices is the story of higher costs for first home buyers, and of windfall gains to existing owners.

Most of us grasp this symmetry instinctively. We see the conflict. Landlords don’t offer discounted rents when official interest rates go down just because they are saving some money on their mortgage. They try to increase rents if the market can bear it and they only reduce them if the market can’t bear it.

The dream of cheap housing is also the dream of bad investment returns for investors (landlords).

The symmetry of property markets does not mean there are no win-wins. When a property owner develops new housing for a buyer, that’s a win for the buyer and developer. One of the most useful insights that economics offers is that voluntary trades are a win-win for both participants.

But once all the win-win trades are made, a market converges to a point that economists call a market equilibrium. This is the price and amount of housing where no one can be made better off through voluntary trading; therefore, from here, making someone better off means making someone else worse off.

A market equilibrium is a beautiful concept. But the property market equilibrium also creates a political and economic conflict around housing policy that cannot be ignored. If we want to change the market from its current equilibrium, someone must lose, economically, for someone else to win.

As it happens, I have been a renter, a landlord of multiple properties, and a homeowner over the past two decades, experiencing both sides of the market first-hand, often at the same time. When wearing my landlord hat, I never desired for my leveraged housing asset to fall in value and my rental income to decline. But at the same time, wearing my renter hat and aspiring to own a home to live in, I wanted to save money on the rent and be able to buy a home in a desirable location with my income. I could feel the symmetry of property asset markets firsthand. If rents and prices increased, that was great as a landlord – I got more cashflow and higher asset values – but it also made renting more difficult, and the price to buy a place of my own further out of reach.

Bizarrely, we treat this inherent economic conflict as a social taboo in polite circles. As a result of years of lobbying and propaganda, you would be forgiven for believing that landlords want nothing more than to offer tenants cheap rents, and speculative housing developers want nothing more than to flood the market to push down house prices.

But property owners have an incentive to keep housing expensive, not cheap. Housing is their asset after all.

Much of what we read in the media about housing is not factual or analytical. What we read are stories crafted by property insiders at expensive lunches with paid shills touting ever more audacious political slogans and marketing angles. Not only landlords and land speculators, but banks and real estate agents all have incentives to tell porkies about the property market that suit them, not you. Whether those stories contain a grain of truth is a secondary matter.

Every change to the market equilibrium – whether through tax settings, planning or tenancy rules, or financial regulations – has a loser for every winner. Every time a renter or non-property-owner wins, a property owner loses.

No doubt in Henry George’s time in the late 19th century, vested interests were also prolific with their propaganda. But the problem now goes further. Today, we have a hijacked housing debate. Whether it is the media, property interests, housing researchers, political parties or governments, they all actively avoid the taboo of acknowledging the symmetry of property asset markets and hence avoid fact-based discussion and actual policy ideas that achieve cheaper housing. This taboo means that opposing economic interests can freely claim in the press that what is good for them is good for everyone, without being challenged, and ignoring the basic contradictions.

Just like the pharmaceutical companies don’t want to cure disease, and the military hardware companies don’t want to prevent war, these groups don’t want cheap homes. They aren’t players in the game but are a type of Housing Cheer Squad that sings from the sidelines and sells political promises, academic analysis, media articles, advertising, and culture war signalling. They thrive on non-specific language that confuses more than it informs.

For the media, ignoring the symmetry of property asset markets allows them to have scary headlines whichever way the housing market is moving at the time. If rents fall, you can have the headline “Good for renters”, but most newspapers prefer “Landlords fear low rents will reduce supply”. If house prices rise, its doom and gloom for first home buyers, or an investment opportunity for landlords.

There’s no attempt at internal consistency and, since any article about housing gets clicks, there is always an incentive to present the most recent data in its most extreme version. Consumers of online news will mostly get shown to them the most exciting data that relates to them – the suburbs where prices rose or fell the most, but less about average trends or other relevant economic context.

For example, during 2022 in the United States, widespread media reporting talked of a home ownership crisis. But, as economist Dean Baker from the Center for Economic and Policy Research repeatedly pointed out to journalists, home ownership had been rising since 2012, when it bottomed out after the financial crisis. If there was a crisis, it wasn’t happening in 2022. But the press just knew that rising prices must be bad for aspiring buyers, even if the truth was that it was the existence of so many new first home buyers that was partly causing prices to rise.

No wonder most people have no idea what is happening in the housing market.

2. What construction productivity crisis?

Cameron Murray and Geoff Hanmer

Australia’s Productivity Commission (PC), alongside various state agencies, private organisations and, most notably amongst politicians, former economics professor Dr Andrew Leigh MP, now the Assistant Minister for Productivity, Competition, Charities and Treasury, have coalesced around the idea that construction productivity is a major problem, particularly in the housing sector.

Economic fashions versus the evidence

Way back in 2012, there was another productivity crisis. At the Australian Conference of Economists that year it was widely claimed that Australia’s corporate managers were the problem. If only our pesky managers would up their game, we could grow our magic productivity beans into GDP much faster.

Now? The fashion is to say that we need to get rid of pesky planning and construction regulations designed to manage urban growth and building quality, even in the context of studies showing that over 70 per cent of new apartment construction is built with serious faults.

According to the PC, the solution is to deregulate planning and building in order that a construction industry left to its own device will plant those magic productivity beans left behind a decade ago, thus increasing the rate of production of new housing and pushing down prices.

The construction industry is cheering this on, because they know that less regulation will allow them to increase profits, whether or not any more housing is built.

What’s old is new again in the fashion cycle of economic thought.

Back in 1985, economist Steven Allen sought to understand “[w]hy construction productivity is declining”. Further back, in 1967, Peter Cassimatis said that “[a] persistent view in the economic literature is that productivity growth in construction is far below the national average.”

In this new era of recycled crisis-concern trolling, this theme has been reprised in multiple reports which fail to produce clear evidence of a problem, and in attempting to do so, incorporate flawed economic reasoning.

Here are the major flaws in the PC’s report on construction productivity.

First, despite pointing the productivity finger at the cost of town planning and design, these costs are not actually measured within the cost of construction. Rather, they costs are incurred within the professional services sector. Only the cost of construction contracts with builders after these planning and design processes are complete are included within construction cost figures. The PC’s analysis used as their measure of construction productivity the value-added of construction contracts per on-site worker. Yet this metric cannot tell us anything about a link between design or planning costs and housing output, because these service inputs aren’t included in the cost of the construction contract.

Second, any new productivity-enhancing construction method that shifts production off-site is counted in these statistics as manufacturing. The Productivity Commission even notes that “offsite production of prefabricated buildings and building components” is “captured within the manufacturing industry” (p15). So when we do see construction productivity-enhancing technology, which usually means moving construction off-site, the benefits of this improvement will not show up in construction sector productivity metrics.

We are being tricked by our industry classification structure into seeing construction productivity decline, due to what remains classified as “construction” being only the remaining on-site processes that have not been moved off-site.

Third, the PC claims that higher construction productivity pushes down home prices. Yet, by historical standards, we have not only adopted better construction methods, but, as incomes have risen, have built bigger homes at a higher density in preference to delivering smaller, cheaper homes. This explain why housing rents and prices remain a concern in 2025, just as they were back in 1911, when NSW held its first inquiry into housing rents.

Fourth, the observed variation in these measures of construction productivity is simply implausible as a guide to actual technical proficiency in converting input to output. Apartment construction productivity as measured by the PC, for example, rose by 86% in six years from 2008 to 2014, only to fall by 30% over the following five years. Does anyone really believe we got 86% better at building apartments within a few years — and then forgot these lessons mere years later?

Australian construction technology wins

In reality, Australia is one of the world’s most prolific and innovative home-building nations.

Historically high wages for construction workers have fuelled innovation, pushing construction companies to reduce the amount of labour used on site by way of prefabricated products and better assembly techniques.

Some recent examples of this innovation include:

Pre-cut and pre-bent reinforcement for concrete made in a factory and transported to site to be tied into place by low-skilled workers.

Factory prefabrication of house frames and roofs. Often, the whole of a house frame, either timber or steel, will arrive on the back of a truck, like a kit of parts, to be assembled on top of a concrete slab by low-skilled workers.

Plastic plumbing for pressure pipes. (Plastic drainage pipes have been used since the 1970’s). Easy to cut, using simple connectors, and easy to assemble on site by low-skilled workers.

Elimination of gas in favour of electric appliances reduces the need for skilled gas plumbers.

The split door frame, which is made in a factory and can be installed by low-skilled labour.

Prefabricated joinery elements, which are assembled on adjustable plastic pedestals to allow for sloping floors.

Use of laser set out tools to allow accurate set out without resort to time consuming string lines and levels.

A decline in the use of masonry and render and an increase in the use of external panel finishes and plasterboard to reduce the amount of skilled labour needed on site.

These innovations aren’t flashy, and can be hard to miss. But they are exactly the boring, incremental, improvements in construction productivity that happen year on year, regardless of the economic and policy fashion cycle and flawed metrics fuelling it.

3. A strange obsession over built form controls

Tim Helm

The Grattan Institute, one of Australia’s most influential public policy think tanks, has been a major contributor to public debates on housing affordability in recent years – but has veered ever more sharply towards “deregulate and hope” policy recommendations as time has gone on.

Their latest work, a speech to the Housing Now! conference in Sydney, is remarkable for what it reveals about what the key influencers in Australian housing policy deem worth talking about.

And it raises the question: how did Grattan and so much of the housing discourse arrive at this single-target obsession with providing capacity by way of slashing built form controls?

It is reminiscent of the zero-COVID era, with one number to rule them all, and no regard for trade-offs.

Let’s look at what’s included and excluded from their latest piece.

The only outcome measure is the median multiple – the ratio of median house price to median income

But this metric has barely anything to do with housing supply and demand fundamentals, since asset prices are driven mostly by interest rates and tax policy.

Monetary policy easing by the Reserve Bank of Australia and the new First Home Buyer loan guarantees being provided by the Australian government are set to lift house prices in coming years. When that happens, will Grattan conclude that upzoning in NSW has failed – or that it hasn’t gone far enough?

Grattan’s policy discussion is 100% focused on built form regulations – with no mention of public housing or taxation

Even given the state focus of their speech, if the goal is simply to dampen housing asset prices, then state-based value capture – taxes or other mechanisms to socialise the rising value of land due to public decisions – could readily achieve that.

Also missing is any discussion the impotence of state policy in the face of what is basically a federal problem of wealth inequality, which is what inevitably lies behind unequal access to well-located land.

Free markets cannot fix poverty, or redress inequality, and rich people always get the best land – yet these fundamental facts about the limits to markets and the drivers of distributional outcomes are ignored in Grattan’s overriding focus on regulation.

There is an overwhelming focus on capacity, and an obsession with the micro-details of specific controls

Grattan argues, for example, that “the [NSW government’s] Low- and Mid-Rise Housing Policy has boost zoned capacity for more housing across Sydney by 700,000 homes” yet if Council floor-space ratio requirements were overridden “the zoned capacity uplift from the reform would increase by up to 400,000 dwellings [more]”.

No doubt this fact is true. But what is missing is any context for what this extra capacity would achieve. The underlying assumption is that finding the magic formula for affordable housing is a technocratic problem, a matter of calibrating the regulatory machine just so (yet always in one direction: more capacity).

In this respect, Grattan misses the forest for the trees. Zoning can shape the look and feel of an area, but it is market incentives that determine how much housing developers will build. Providing more capacity, when excess capacity is currently being landbanked, is like pushing on a string.

Auckland. Australian commentary paints a picture of housing utopia – just across the ditch!

But don’t fact-check that with any of the Kiwis flying from AKL to SYD today. A net 30,000 New Zealanders moved to Australia last year, the highest rate of departure since 2012.

Grattan’s key chart on Auckland, reproduced below, misleads readers as to the drivers and effects of Auckland’s much-vaunted 2016 zoning reforms.

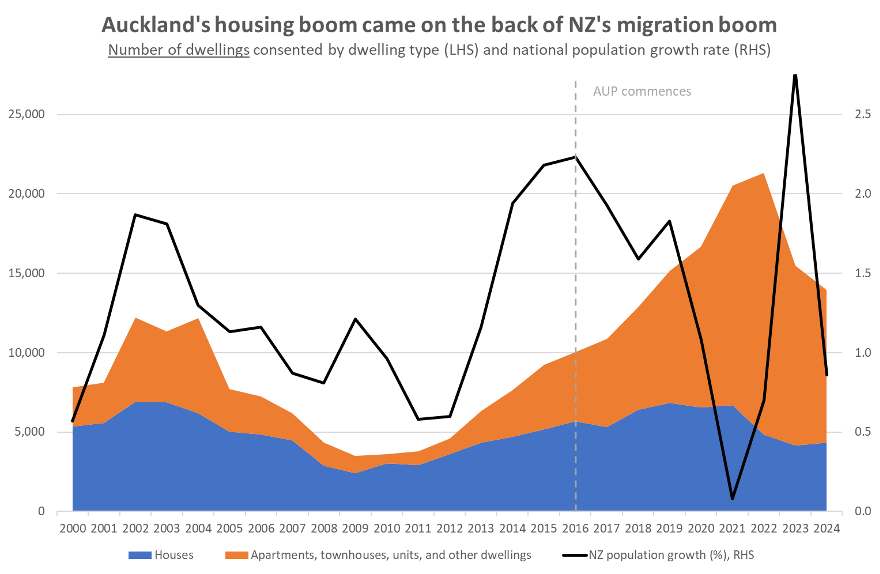

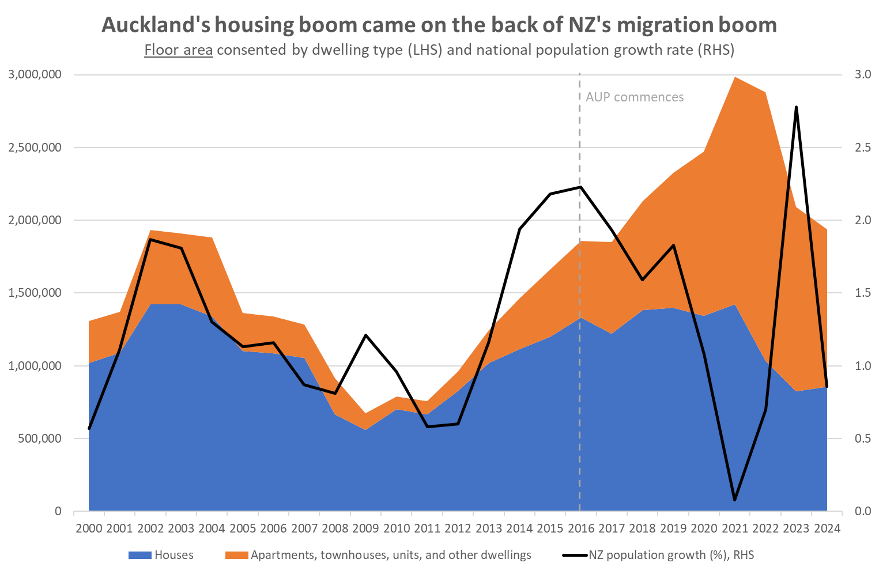

Auckland did see a huge post-2016 housing boom, as well as a significant compositional change driven by the reforms.

But adding the latest two years of data, omitted from their chart, shows clearly how this cyclical boom was, well – cyclical.

The real story here is that NZ tripled its population growth rate between 2012 and 2014, then sustained that OECD-leading rate right up until COVID. Housing construction has been playing catch-up ever since.

As interest rates rose through 2022 and 2023 and the population effect of COVID-era border closures worked their way into fewer new housing orders, new dwelling consents (a.k.a. permits or approvals) fell away.

The number of dwelling consents issued in Auckland also masks the effects of compositional change, with new dwellings now much smaller than before the reforms. On a floor area basis Auckland is consenting barely more than during the early 2000s boom, despite the city’s population now being 40%+ larger.

Auckland’s housing cost-to-income ratio is also no lower than before the reforms, and between 2018 and 2023, 20% more Aucklanders left the city for other parts of NZ than over the five years prior. None of this screams “affordability miracle”.

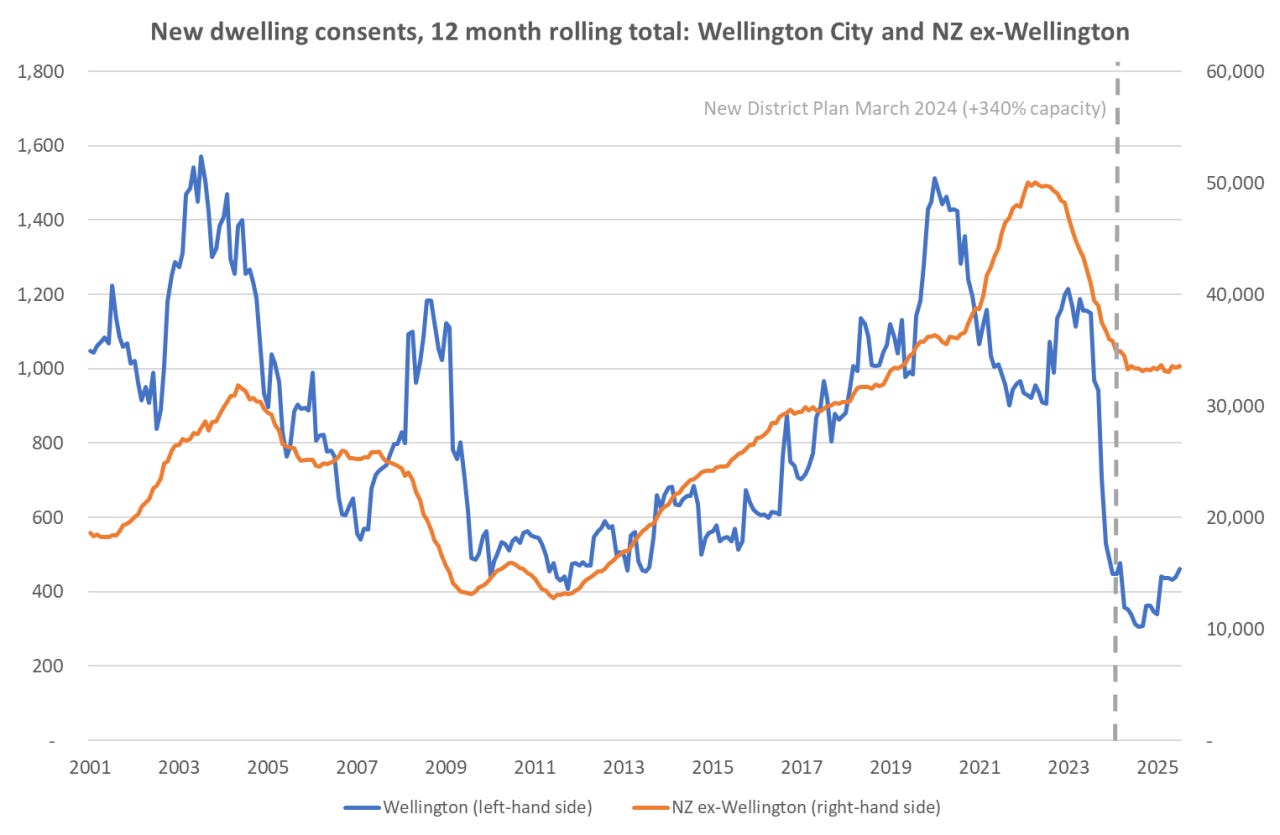

How important is it to flood the market with capacity via upzoning, as Grattan urges?

There is something to be taken from the experience of Wellington City, which quadrupled zoned capacity in March 2024 – at a very different point in the market cycle to Auckland. Dwellings consented quickly hit their lowest levels since the 1992 recession. Adequate capacity is evidently necessary, but not sufficient.

One can remain agnostic on zoning rules – they’re a matter for democratic decision-making – while recognising that policy advice should at least begin with a clear acknowledgement of their intended purpose and value.

Zoning regulation is explicitly meant to stop developers doing whatever they want at the expense of the locals. If you don’t appreciate that goal – and there is no evidence Grattan does – then of course you’re going to want less of the regulation.

In this context Chesterton’s fence comes to mind: if one cannot articulate the purpose and value of some rule, policy or institution put in place by past decision-makers, is one really in a position to advise on its ongoing relevance?

The problem with Grattan failing to understand this purpose, and being missing in action on the real economic drivers of housing affordability, is one part opportunity cost – because quality minds are lost down the rabbit hole right now – and one part distraction – because all this trade in snake oil is leaving real housing solutions on the shelf.

A clearer framework for understanding housing outcomes starts with this: land is fixed, inequality is rising, and interest rates have fallen. Those are the big three drivers – and the rest, including zoning, is peripheral.

As always, please like, share, comment, and subscribe. Thanks for your support. You can find Fresh Economic Thinking on YouTube, Spotify, and Apple Podcasts.

Interested in learning more? Fresh Economic Thinking runs in-person and online workshops to help your organisation dig into the economic issues you face and learn powerful insights.

I agree with many of the points you make: productivity measures are invalid, prices are set by economic fundamentals (tax policy, interest rates), and more.

But I take issue with this: "Free markets cannot fix poverty".

WAT? What if not free markets lifted billions out of poverty in our lifetime?

Although it is true that we're a democracy, we're also a liberal democracy and more importantly an extension of English civilisation. A civilisation who's success was tied to the respect for property rights and voluntary exchange. Unless a liberalised construction market was imposing massive externalities, shouldn't freedom be the default. Shouldn't the oweness be on the planners that need to justify the zoning rules other than "we had them forever" and/or "the people like it".

(If you're going to point to the pressure on the transport system, we could simply manage that using road user charges and congestion fees. Regulating construction seems like an absurd way to solve the problem created by tax funded roads)