Is Antarctica the new Wild West of cowboy property claims?

Why property rights there are going to really matter very soon

A recent episode of the B1M show covered the new construction boom happening in Antarctica, spurred on by oil discoveries of Russian geologists.

I’m a property nerd.

I find the way we assign new property rights to be a fascinating insight into social and economic processes.

Antarctica today is in a rare situation where property rights are emerging on a new continent with little institutional baggage.

The colonisations of the British typically adopted the property rights systems of the mother country, with positions of power in the new institutions filled by those raised in the existing traditions.

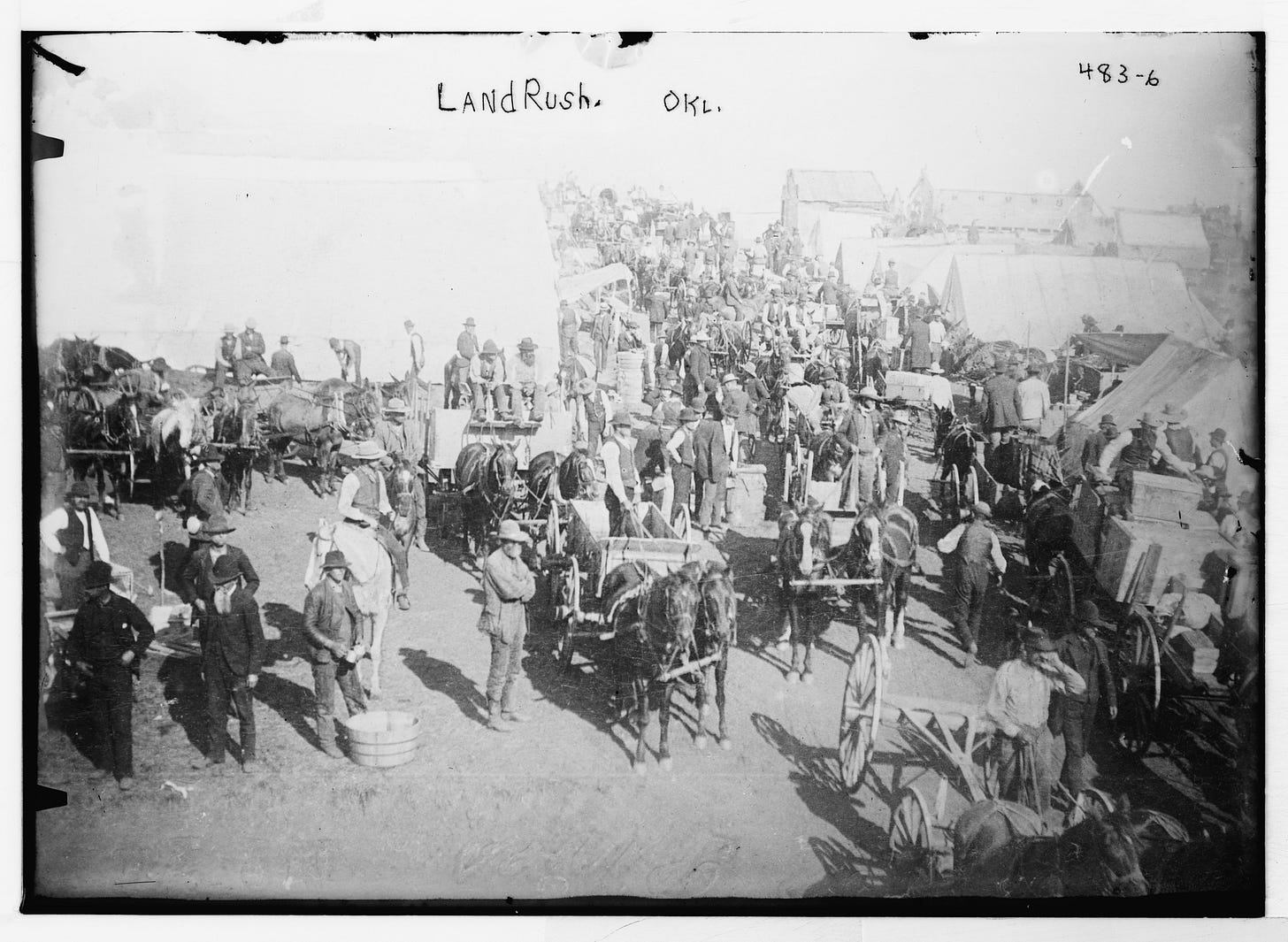

The United States is an obvious case and has many interesting examples of how property rights systems emerge. One of my favourite situations is the Oklahoma land rush of 1889 when unclaimed lands were allocated to those who got their first from outside the area following a high noon starting gun.

Like most other times new property rights were established, there was intense conflict despite the attempt at order.

The invention of flight similarly tested our understanding of property and how we regulate access to the new realm of airspace.

Was flying over a farm a new form of trespass? Or did new property rights to airspace supersede them and create a vertical limit to those old rights?

Similar challenges will arise in space as orbits become more popular. Claims on the Moons and Mars must be resolved. Currently, space is regulated via a similar treaty to Antarctica, the Outer Space Treaty, which prohibits territorial claims by countries.

I don’t know how far in the future those situations will arise. Lucky for me, Antarctica looks to be a frontier where a new property rights regime is likely to emerge from scratch during my lifetime.

Will the process be intertwined with conflict like when colonial property rights took over new frontiers? Or will we take a more measured path along the lines of regulating airspace rights?

I don’t know. But it will be fascinating whichever way it goes.

With that in mind, please enjoy this article of mine from 2018. It seems especially prescient looking back from 2024 and gets to the heart of the issues around conflict, coercion, and the establishment of valuable systems of property rights.

Who really owns Antarctica?

I have often argued with libertarians (and anarchists) that the existence of property rights first requires the existence of a government with a monopoly on coercive force (ie. government requires the largest armed force). If such an entity didn’t exist, then the largest armed force would simply take control and become the government. Many voices in these debates suggested that I need only look to international treaties to show how cooperative we can be without the need for world police.

Putting aside the obvious point that the United States is the current world police, with their military budget making up 43% of the world's total military spend, and that their international military presence often conflicts with international treaties, we can examine whether libertarian views are vindicated by one of the shining examples of international cooperation—Antarctica.

Back in 1959, twelve countries active in the Antarctic signed the Antarctic Treaty (implemented in 1961), which led to further treaties and conventions to manage activities and resource use (especially fisheries) in the whole Antarctic region south of 60% latitude. Collectively these treaties are known as the Antarctic Treaty System. With the shadow of the Second World War still looming large, the top priority of the original treaty was to ensure that the area remained conflict-free by outlawing a military presence—prescribed in Article I of the treaty. Other peace-inspired provisions include Article V, prohibiting nuclear explosions and the disposal of radioactive material. Who knew that the dominant ideologies of 1960s youth originated in Antarctica?

Since that time the Montreal Protocol was adopted as part of the Antarctic Treaty System with the explicit intention of preserving the Antarctic as a natural reserve devoted to peace and science. Critically, Article 7 of the Protocol prohibited all non-scientific mineral resource activities.

The Antarctic Treaty was a bold and lasting agreement, recently celebrating its 50th year. The treaty’s anniversary gave rise to some optimistic claims

The lesson of fifty years of the Antarctic Treaty System is that the nations of the world can set aside their political and territorial aspirations to share in the management of a vast region of the planet, says Paul Berkman, chair of the International Board for the Antarctic Treaty Summit.

But I wouldn’t make such strong claims so fast.

Geopolitics was not cast aside by the free love of the original Antarctic Treaty. The United States does not recognise the territorial claims of other governments and reserves the right to assert claims. The USSR, and later Russia, made the same non-commitment to the Treaty. The success of the Antarctic treaties over the past fifty years was perhaps more the result of the low value of any commercial or strategic military operations in the Antarctic.

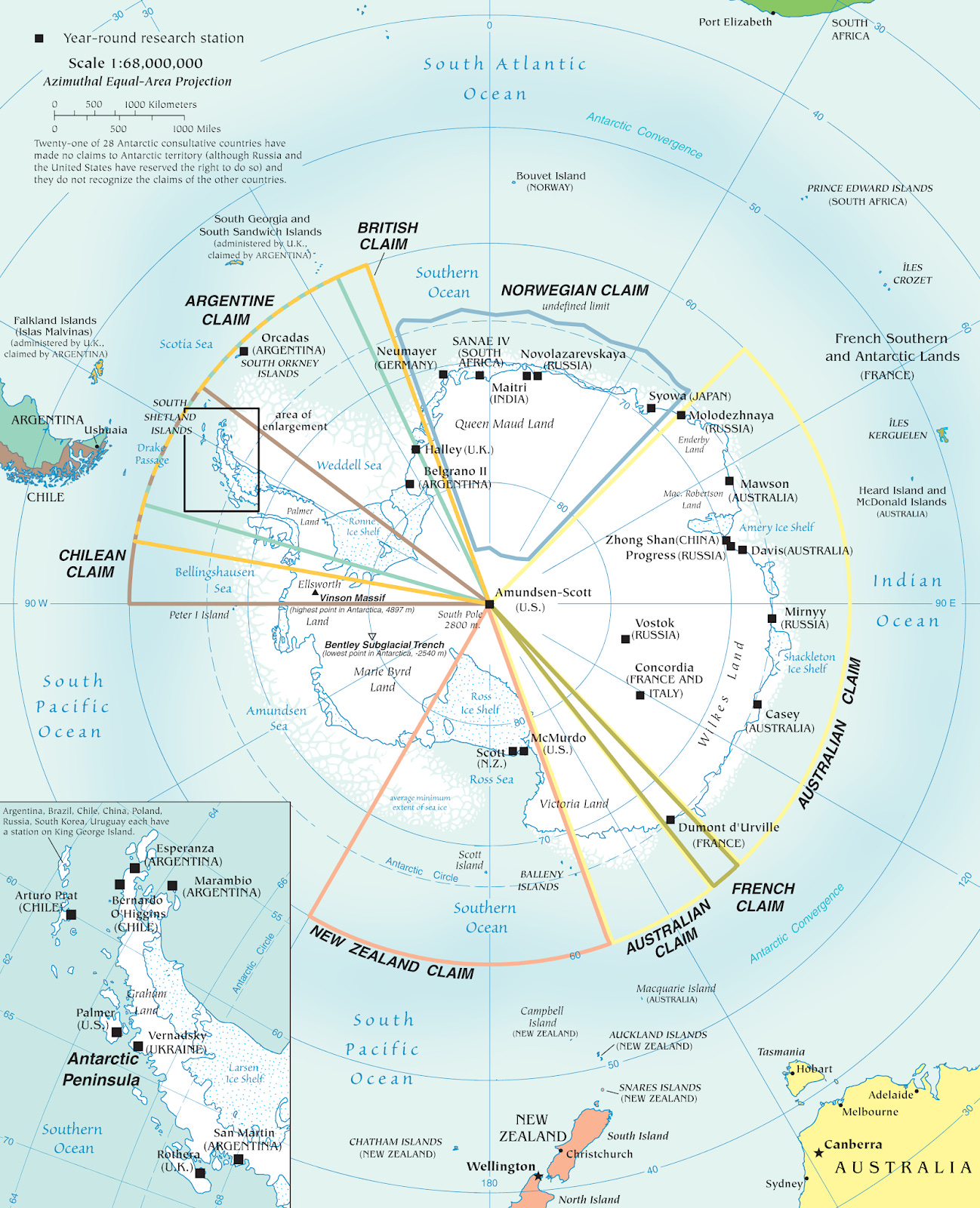

While the US has no current claim over territory, it has positioned its Amundsen-Scott research base at the South Pole to maintain a presence in all claimed territories (shown in the map below). The United States may very well have secured a right to claim territory that existing claimants leave unoccupied.

We also know Australia does not have the capacity to visit the inland areas of its territorial claim. This may be problematic as the original Antarctic Treaty has a provision in Article XII allowing a contracting party to call a review of the operation of the treaty after thirty years. One could expect that our absence, or lack of presence, in our claimed territory, puts us in a poor position for any future treaty negotiations that may establish new claims based on current activities.

The rise of new entrants into Antarctica is also concerning for existing territorial claimants.

Russia has seven stations in the AAT; China opened its second station last year; India will start construction on its first over summer; and South Korea is planning to set up a new station near the Easter sector by 2014.

With renewed interest from emerging global economic powers, and the ice sheets receding in some areas, mining the Antarctic is attracting a lot of attention (and here).

So it seems that the ingredients for conflict are slowly being added to the spicy Antarctic political stew (these concerns have been noted elsewhere). How one resolves these new interests in the mineral rights of Antarctica, with the interests of the existing parties to the Antarctic Treaty System, I am not sure. But let’s be clear. The United States will not lose out in any future negotiations that allow further exploitation of the Antarctic. In a hypothetical future scenario where mining becomes allowable under the treaty system, does anyone really expect the US to respect the rights established by existing territorial claims? I don’t.

In the end, current Antarctic territorial claims are only valid as long as they are not challenged. So I ask the anarchists and libertarians, exactly how does one negotiate a territorial claim (or defend their property right) with an unmatchable armed force that happens to be a necessary military ally?

> So I ask the anarchists and libertarians, exactly how does one negotiate a territorial claim (or defend their property right) with an unmatchable armed force that happens to be a necessary military ally?

I think you misunderstand the anarchist libertarian position (BTW, not all libertarians are anarchists, some will agree with you that a state is required to guarantee property rights).

I don't think libertarian anarchists will dispute the fact that potential force is required to guarantee rights.

I think you're drawing the wrong conclusion though from what's going on in antarctica.

The relevant conclusion to draw is that parties can have competing claims and resolve disputes without a central authority, without a total war, and without the strongest party ending up with full control.

However a potential conflict in antarctica will unfold it's unlikely that we'll see a major military confrontation, or that one country will end up controlling the entire continent. That is, property rights (between nations) will be allocated relatively peacefully, and I would guess in proportion to the "investment" of the nations in the continent.

If you're concerned about individual property rights vis-a-vis nations, that's a different question, but it's not what libertarians talk about when they draw on international affairs for an analogy of anarchy.

> I have often argued with libertarians (and anarchists) that the existence of property rights first requires the existence of a government with a monopoly on coercive force (ie. government requires the largest armed force). If such an entity didn’t exist, then the largest armed force would simply take control and become the government. Many voices in these debates suggested that I need only look to international treaties to show how cooperative we can be without the need for world police.

I always thought the idea of property rights enabled by a state monopoly on violence was a mainstream view. I don't even understand why libertarians and anarchists don't believe this given I also identify as a libertarian.