The great housing supply contradiction

This time the contradictory stories about rent control and housing supply are in Minnesota

Rent control fails once again. Ha ha! It’s ECON101 dumb dumb.

Do I need to teach you that again?!

That’s what they all sound like in my head. Never mind the facts. Blurt out whatever you like.

It is happening now with calls to limit rent increases on existing tenants in Australia.

But almost without fail, those who yell the loudest hold two logically incompatible views on housing supply, which I call the Great Housing Supply Contradiction.

More on that in a moment.

The Minnesota case

Here’s a recent example that stood out to me.

A chart like that can appear pretty convincing.

However.

St Paul’s rent control began in May 2022, yet this compares periods in 2020 and 2021.

The chart shows only November to January periods. Other similar charts show November to April periods. Yet even now only preliminary data exists for any month in 2022.

The rent control ordinance only limits rent increases to 3%.

New dwellings can apply the market rent at the time they are first rented.

The text of the ordinance is here (and more detail here). In general, it looks okay. It is a little unusual in that the rental limit applies even when there is a change in occupancy.

I don’t see that being a major issue.

But I have a hard time believing that the variation in building permits in that chart is due to the economics of this rent control ordinance.

Rent controls are a soft consumer protection

The St. Paul rent control ordinance allows a maximum of 3% annual rental price increases, but allows higher rental increases under particular circumstances like landlords renovating, or the number of tenants changing.

So the law only has an effect if the market rent is rising faster than 3%. Otherwise, it does nothing. Are rental increases above 3% even common?

Since 1984, the rental CPI in the Minneapolis region has risen by less than 3% per year on average through all those ups and downs. It increased by more than 3% about half the time and by more than 4% about a quarter of the time.

I’ve plotted the rent control limit versus the CPI rental index in the chart below since 1984. These rental price paths are not that different.

For multifamily landlords of new housing projects, the new rent control ordinance mostly smooths out their future cashflow stream without greatly changing its present value.

Nothing to panic about.

Look at all the data

It is also weird that these claims about the terrible effect of rent control compare two arbitrary time periods in the years prior to the actual law and infer that the difference between these years is due to some future uncertain rent control event.

Why not look at the long-term trends and see if there is anything there?

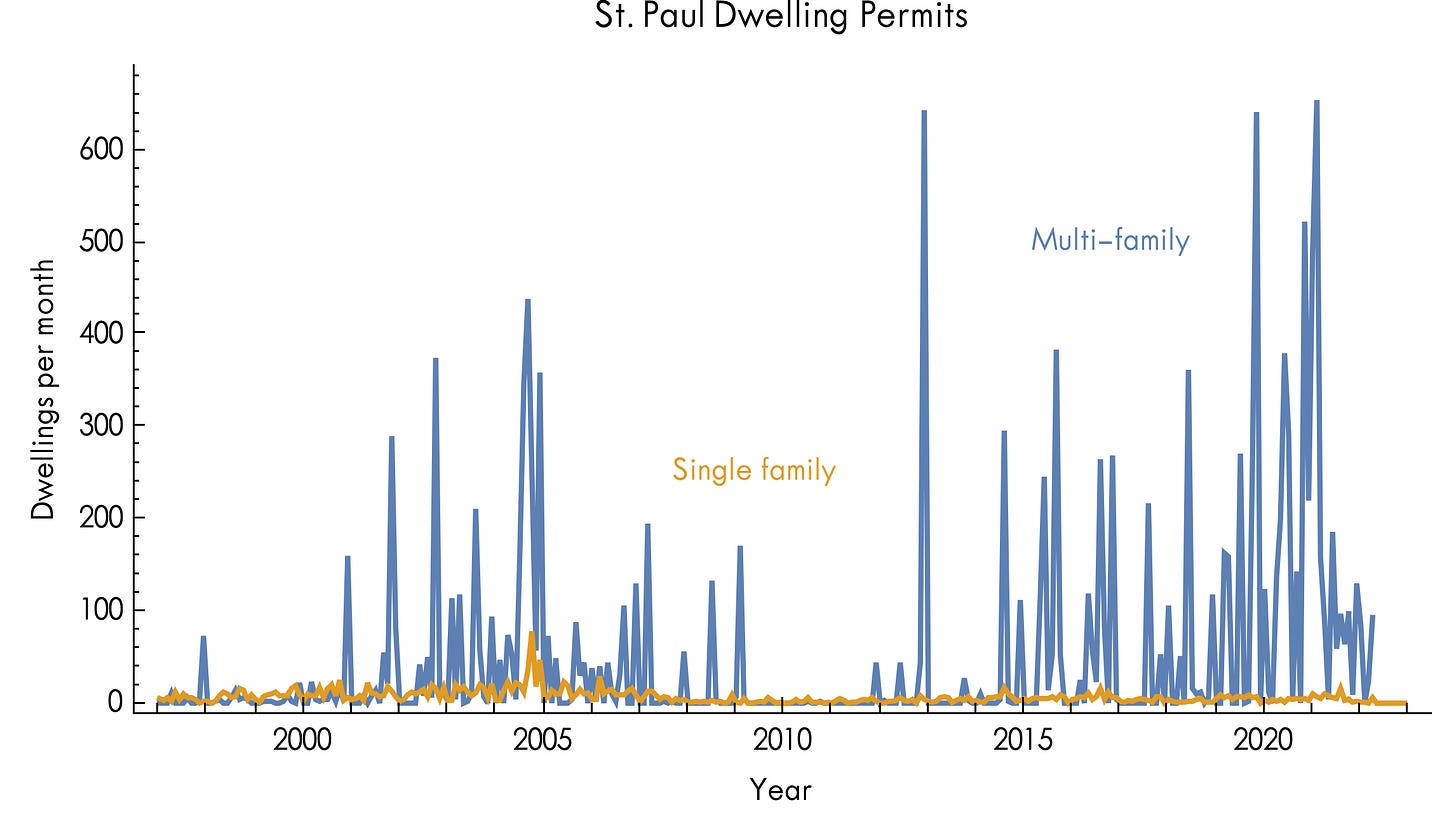

It’s not that hard. I went to the same data source to have a look. Here’s the monthly data for St.Paul for single- and multi-family permits.

We can see a massive amount of cyclical and random variation. Here’s the data for Minneapolis which likewise shows high-frequency variability.

Of course, the data for 2022 is preliminary. Meaning it is incompletely reported. So we don’t really know anything much. But I can replicate another chart using the November to April period to compare.

My version in the chart looks at that period each year using all the available permit data to see the longer term patterns.

Notice that Minneapolis multi-family permits crashed in the prior year by as much as St. Paul in 2022. Then they switched. It is not clear what story fits this data. But if you want to say that rent control caused the big downturn in preliminary reported data in St. Paul, then you need some way to differentiate that change from all the other variations in the data. It could just be a reversion to the mean from the unusual 2021 year.

The Great Housing Supply Contradiction

What this “Twitter barney” has revealed to me is that most people aren’t really serious about analysing with rigour subjects they care about.

I also feel silly that it took so long for me to realise why I get confused by debates about housing supply and rent control. This is why.

It cannot be true that rent controls stifle new housing supply and also that private property markets will supply enough housing to bring down rents.

This is the Great Housing Supply Contradiction.

The below chart shows that if the housing development market really functions in a way that will bring down rents if left to its own devices, then rent control will have no effect. After all, market rents will follow the orange path anyway because of the actions of private housing suppliers.

Rent control is a total nothing policy that can never affect rents.

If rent control does have an effect, it means that private housing markets won’t supply new housing fast enough to stop rents from rising more than 3% a year.

Major contradictions in the analysis of rent control are common. I’ve written before about how rent control studies label good things as bad things when they don’t suit the “evil rent control” narrative.

A 2014 paper looked at the effect of de-control of rents in Cambridge and found that it massively increased rents and housing prices.

Yet I just listened to a podcast where other economists were saying that this paper showed how bad rent control was for constraining housing values. This is another case where bad things, like high housing prices, are called good things to save the narrative.

Never mind the contradictions.

You’re looking at the wrong metric, really. Obviously rent control controls rent where it has jurisdiction. The problem is that it changes the sample set, so it has side effects outside of those to whom it applies. Under rent control some housing that would otherwise be supplied in a particular location is not supplied. Whoever would have lived in that housing instead must continue to demand housing where they currently live, thus raising the rent there—but this effect is not captured in the rent controlled jurisdiction. For example, rent increases often coincide with an influx of higher income people moving to a neighborhood or city. Preventing rent increases prevents these people from moving in. Which means the net effect is that they consume more housing where they currently live, raising rents there, or preventing them from falling. Sadly this usually means they live in a place they don’t prefer, and maybe even one where they are less helpful to society due to lack of capital they can skillfully operate. Misallocation of labor due to inability to move into more economically productive regions is a massive, under-the-radar problem. So while your logic is certainly correct about the effects of rent control on the people to whom it directly applies, it misses the point, since much of the harm it does is to people who are not paying rent in the rent-controlled city, but otherwise would have been.

The ACT has legislated limits in rent increases for existing tenants (rental CPI +10%). I suspect the law is not very effective because it relies on tenants pushing back against proposed increases. My guess is most tenants don't know about the limits, and many of those who do judge (probably correctly) that they'll be worse off if they push back