Will removing planning controls crash the housing market?

Recent Twitter exchanges have helped me to understand a couple of additional confusions in the housing supply debates. Let me take them one at a time.

The housing supply mechanism

I dunno, man. There's a golf course just down the road from me where I live in SE London. That land would be worth 10-20x as much with permission-to-build.

You can argue that a massive increase in building wouldn't affect *prices* much but arguing nothing would happen is crazy

— no employers, don't google me (@sudonimbus) August 17, 2020

This Twitter statement contains some hidden assumptions and two main points; 1) that land is worth different market value depending on the rights attached to it, and 2) that massive amounts homebuilding will affect prices.

Points 1) and 2) are correct. But the hidden assumption that because land has a different value with a planning permit (or with different zoning) that overall homebuilding rates will rise if a plot is rezoned. This part of the mechanism is wrong, in my opinion.

It is not obvious to me that changing planning will greatly affect the rate of market supply. If you assume that planning is the reason new housing supply is not higher, then you are assuming the outcome. I don’t think it would do much at all.

This challenge was put to me.

Let's hypothetically suppose that a new regime grants permission to build literally anything up to 10 stories and compliant with building control on any site within 30 miles of Big Ben.

What happens, in your model?

— no employers, don't google me (@sudonimbus) August 17, 2020

I responded that not much would change.

Let us be clear. Many cities effectively have this type of planning system. Sydney councils, for example, allow tall towers in vast areas of the city and had record new housing construction for nearly a decade. That doesn’t stop people from saying these new apartments should be taller, or that supply isn’t a problem.

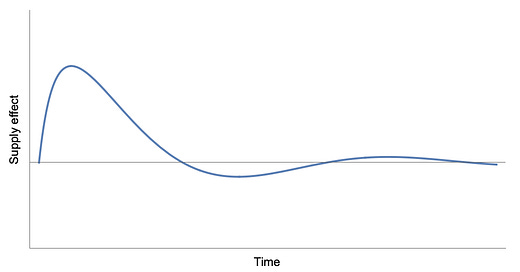

Sure a large scale planning change would be a shock to an equilibrium. It will probably stimulate a flurry of activity—site trades, new types of development proposed, and maybe extra buying of these new dwelling types. During this adjustment period, prices would probably rise rather than fall, as is usually the case. But this would quickly calm down until there is no sustained change to the rate of supply.

The effect will be like any other small shock to a dynamic system.

Developers slow their sales when prices fall, and increase them when prices rise. They build to order. I do not see what mechanism there it so sustain faster supply and falling prices with these economic dynamics at play. Would it make sense for any developer to sell out their apartments at lower and lower prices to sustain a faster sales rate?

The zoning and land value issue

Additionally, the fact that changing zoning, or permitting development, affects the price of a property seems to be evidence about supply constraints for many people.

Not sure the blog helps the author’s argument, as

1) land values and changes in value differ hugely depending on housing permission rights, that supports @s8mb point about interest rates

2) density of rental accom (people per flat and location rel to Work) have deteriorated

— Chris Giles (@ChrisGiles_) August 19, 2020

This exact argument was the second paragraph of a recent RBA paper about housing supply.

There is a hidden assumption at play to make the leap from “different property rights have different values” to a supply shortage. Unless you want to argue that property rights should have no value, then this is a weird argument.

No one would think it unreasonable that if you gave a landowner the rights to use adjacent public space to build extra housing that their property rights would have a higher value. Yet when we change the orientation of neighbouring rights from “beside” to “above” apparently these rights should be worth zero.

We know rights to airspace and higher density are valuable because they can be traded in some markets. They are a distinct property right. Planning is a tool to allocate them.

There are no "true" property rights to land that go from earth to the heavens. With property rights, you get what you are given.

Strangely Ed Glaeser’s approach to housing implies that property rights to land should be worth zero. He says, in essence, housing supply would be effectively unconstrained without planning and land values would fall to zero.

He is careful not to say it this way because it sounds stupid. He instead says that the cost of housing will be pushed down to construction cost. Hence, the land component of home prices will be zero.

This is unusual, to say the least. It implies that if you removed all planning controls (build anything anywhere) that land would become valueless. If this were true, announcing such as policy would crush land value to zero immediately as expectations get factored in. Who would want to own an asset whose value is rapidly trending towards zero?

How you can affect housing prices with “supply”

On the Jolly Swagman podcast I thought I understood you to be saying that housing supply is not the main issue. But then you also mentioned flooding the market with new stock would help and also that artificial drip feeding impacted prices?

— 𝙿𝚛𝚘𝚏𝚎𝚜𝚜𝚘𝚛 𝙳𝚎𝚖𝚘𝚐𝚛𝚊𝚙𝚑𝚢 (@PrDemography) August 19, 2020

The physical number of homes does not change prices much. It was, therefore, confusing to some when I said we could flood the market with supply to reduce prices. If we think about property price crashes, we can see what flooding the supply-side of the housing asset trading market can do. This effect has nothing to do with the total quantity of dwellings. In fact, such price declines are usually accompanied by crashing housing construction.

I also do not claim that developers artificially drip-feed new supply. There is nothing artificial about it. This is the normal market outcome. Another way of saying it is that there is a rate at which they must sell to maximise the value from their land. If the sold faster, they would undermine their own profitability, which would happen because these faster sales had an effect on price. When I looked at developer landbanks and sales data it was common for large approved (<200 lot) subdivisions to go a full year without a single sale. If they wanted to sell, say, 10 lots that year instead of zero, they would have had to drop the price substantially.

"Flooding the market" can be thought of as mimicking the asset-trading dynamics that happen during a house price crash by adding many desperate sellers to the market. A public housing supplier could do this. The scale would have to be very large, but this is exactly the large scale change in supply many expect to happen automatically from rezoning. So why not guarantee that it happens with a public competitor to these private housing suppliers?

An improvement on this "flood the market" idea is to copy how the price of money, the interest rate, is regulated by central banks. They promise to supply reserves (and demand back reserves) at narrow price range around their target rate. Their promise to back these guard-rail prices with a supply of reserves is enough for private market participants to adopt that price. In effect, monetary policy is implemented by announcement. They rarely have to use the guard-rails because they are credible.

Imagine a Central Housing Bank (CHB) with a promise to buy any dwelling at a $300,000 price and sell as many dwellings as desired at $310,000. Obviously, it would be more sophisticated than this with price schedules for different locations and dwelling types. But regardless, it sets a price corridor with a price promise backed up with an ability to supply housing.

If this institution demonstrated its ability to back up its sales with new housing, this credibility would lead the market to accept that price and operate within the corridor. It would realign market expectations on prices and capital gains.

How many new dwellings would need to be built to back up that promise and demonstrate its credibility? Probably not as many as you would think. Yes, there would be waiting lists at first as home production ramped up to back up those sales. But even then there would still be an effect. Pay $500,000 or wait a while on the waiting list and pay $310,000?

I would guess that building about 30,000 thousand dwellings per year for the first few years in Australia would make the CHB credible. Maybe 60,000 per year in the UK.

Now, I do not think this is the best “solution” to high housing prices. I think the best affordable housing system is Singapore's proven model.

What thinking about this option does is show that we do intervene in important asset markets, like money, when we think a different price would be socially more desirable. It also shows how difficult it would be to get prices down via supply-side interventions.

It also puzzles me that those who want low home prices and think homebuilding will get us there usually do not advocate for such systems. Why not advocate to copy Singapore’s model to build every citizen a new home at construction cost? Why not propose to flood the market via a non-market housing developer who will meet their supply targets regardless of how low they have to drop prices?

This report, entitled Help to Build, is apparently a plan to support housing supply, yet it proposes only demand-side interventions. In effect, it concedes that housing supply responds to demand and that we just need more demand to get the supply. If this is true, then it cannot be true that planning changes will result in voluntarily faster supply at the same level of demand.

Likewise, suppliers are unwilling to ramp up output unless they think there will be a prolonged period of high demand since they do not want to start up only to have to switch off shortly after.

This is a long post, so I will stop. Post your questions in the comments.