How evolution opens the black box of market competition

Bad firms die and profitable ones thrive, even when no one knows what they’re optimising

Competition policy, also known as anti-trust policy, is having a renaissance. Even the housing sector is a target, with the Productivity Commission noting that barriers to entry could impede competition in its recent report on homebuilding.

Economic regulators typically rely on simple economic theories of competition, with optimising firms whose incentives are driven by the number of competitors in a relevant market. This is known to be a simplification, so on top of this core theory, other ideas are added in an ad hoc way, such as business failures (exit) and emergent new businesses (entry), and the selection effect of consumer choice.

I argue that this approach gets it backwards.

An explicitly evolutionary approach, which starts with entry and exit within a constraining competitive environment, will generate what looks like optimising behaviour in the aggregate. It also highlights how a lack of competition between firms can lead to competition within firms that reduces efficiency.

Does a different theory result in different policy insights? I’m not quite sure. But I think it offers a more coherent view. Let me know your opinions in the comments.

Here’s a summary of the story I want to tell about the how an evolutionary model of competition works.

Market competition is a selection mechanisms where relatively higher profitability replicates, even if firms are not trying to maximise profitability.

However, the level at which competition occurs matters.

Firms need to be cooperative internally, but competitive externally (like sports teams).

If firms become internally competitive, the fact that some people in the firm gain rank by sabotaging others becomes a problem.

Nevertheless, firm-level selection can rid the market of inefficient and uncooperative firms.

Core theoretical differences

Consider two alternative processes that lead to what looks like optimising in the aggregate.

Process A: Rational firms choose optimally and profitably

Process B: Irrational firms choose randomly, and markets select for profitability

In Process A, all firms are rational. No one goes bust. The future is well known in advance. But in Process B, firms start and fail all the time, and it doesn’t matter whether we can know the future because agents who survive in the market will be those who have so far successfully predicted the future (well enough to survive) in terms of their internal operations and consumer preferences.

When we observe the outcome of both processes, it will appear that the surviving businesses we observe are optimising to maximise profitability and meet consumer preferences, as higher profitability means a greater chance of survival.

That agents—firms, customers, etc—who make somewhat random decisions under constraints can still generate emergent market-wide outcomes that exhibit what looks like optimising behaviour was noted by Gary Becker decades ago.

I explain that logic in this article:

Here, I dig further into the idea that the best models of competitive markets are evolutionary ones that embed the idea that cooperation and competition operate at different levels, rather than models of perfectly informed optimising firms.

This approach synthesises many insights about monopoly power versus competition, and the existence and persistence of firms themselves as low-cost coordinating devices (a la Coase).

An evolutionary approach

The main starting point in an evolutionary model of competitive markets is not to assume that people or firms know the best way to organise or what to produce. They only learn by doing, and it is the interaction of that doing (experimentation) in markets of other experimenting firms and individuals, that selects for what looks for profitability and what looks like optimised behaviour.

The core ingredients of any evolutionary process are

variation,

selection, and

replication (inheritance).

In the natural world, genes vary a little over each generation of an organism through the recombination of parental genes. The environment selects for which genetic traits produce more offspring, which replicates those genes at higher rates in the next generation.

Firms are organisms in a market environment. They can adapt over time, but sometimes not enough for a changing environment and go extinct. New firms can emerge by recombining other resources, and existing firms can evolve in response to selection pressures.

What makes a firm, or business, a unit of evolutionary selection and not the individuals within it? We usually think of traits of individual animals, not of the traits of a herd of elephants or a pride of lions.

This is where the insights of David Sloan Wilson come in. He is one of the scientists who showed that evolutionary processes act simultaneously at multiple levels—the cell, the organism, and the tribe of organisms. The theory is called multilevel selection.

This is much clearer when we think of animal species like bees, where the hive acts in such a cooperative way internally with multiple set roles for different creatures, that it doesn’t make a lot of sense for individual bee traits to be selected for in the environment, but that traits of the whole hive and its behaviour are what are selected for by the environment.

In my approach, firms are like a beehive, where the internal cooperation is what leads to success in an environment of competition with other firms (other hives). Firms cooperate internally to compete in an external evolutionary environment.

Let me explain.

Cooperation and competition at different levels

Imagine that within a firm, every interaction amongst employees can be either cooperative, which results in improved production efficiency, or competitive, which helps one of the individual employees (conditional on the other being cooperative), but reduces the overall efficiency of the firm.

It’s like facing a prisoner’s dilemma repeatedly for every internal company decision.

Uncooperative behaviour might be as simple as employees wasting resources, blaming others for failures rather than working together to get an efficient outcome, or it could be as competitive and nasty as sabotaging the work of others in the firm to make yourself look good, which might be good for the individual, but bad for the company.

Cooperative behaviour might involve groups quickly agreeing on incremental innovation in processes to remove duplication and waste, or implementing new products or designing new production methods, and so forth.

There is really no obvious recipe for cooperative success that can be enacted in advance. Trial and error within and between firms is necessary.

An example from Amazon can help get your mind around the idea that it really is hard to foster internal cooperation and avoid conflict within firms:

At Amazon, workers are encouraged to tear apart one another’s ideas in meetings, toil long and late (emails arrive past midnight, followed by text messages asking why they were not answered), and held to standards that the company boasts are “unreasonably high.” The internal phone directory instructs colleagues on how to send secret feedback to one another’s bosses. Employees say it is frequently used to sabotage others. (Source)

A process designed to increase cooperation and get groups to an efficient outcome can easily be sabotaged and result in costly conflict. But who could know that in advance without testing the system by implementing it?

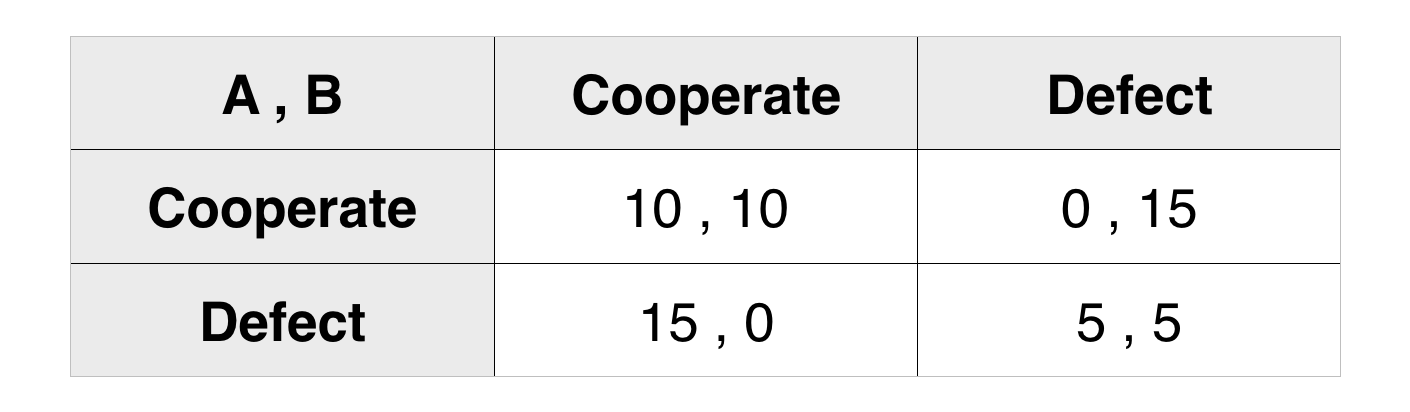

The table below shows the stylised conflict between individual choices to cooperate or compete within a firm. For two people (A and B) who randomly meet within a firm, they can both cooperate and earn an individual payoff of 10 each (top left cell with A, B individual payoffs listed), giving the firm an overall payoff of 20. Or, one person can defect while the other cooperates, giving that person a payoff of 15, but only a payoff of 0 for the cooperator, and an overall firm payoff of 15, which is lower than if people were cooperating. And the bottom right cell shows the payoffs if both people are competitive (the defect from cooperation), giving each a lower payoff of 5, and the firm a payoff of 10 (the sum of both people’s payoffs).

Clearly, the best thing within a firm is for all interactions to be cooperative to get the highest total firm payoff, but there remains an incentive for each individual within the firm to occasionally defect and get a higher personal payoff.

Now, let’s think about market competition operating at a firm level. With more competition, would we expect the evolution of the market to result in the success of more competitive individuals or more cooperative individuals?

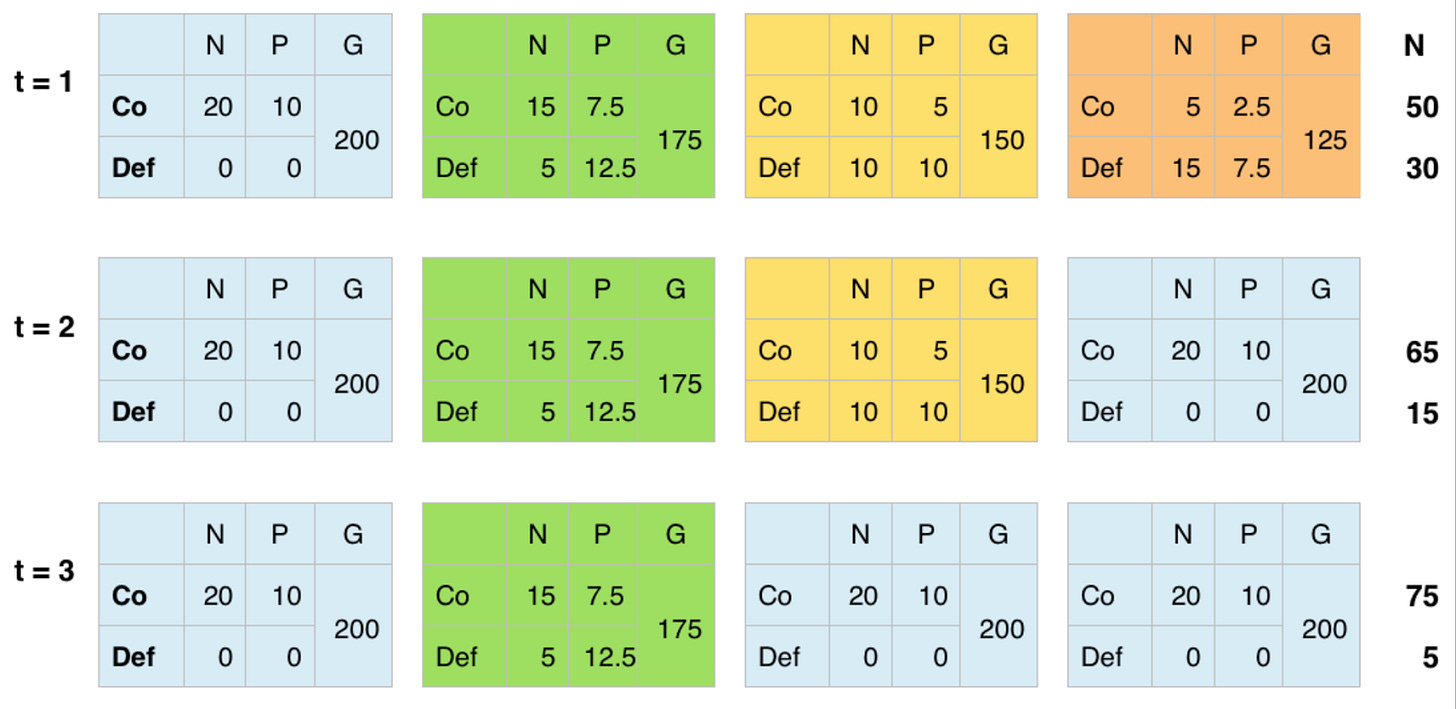

The diagram below shows a series of three selection stages down the rows from time one to time three. Each colour represents a single firm. So in the top row, there are four firms (blue, green, yellow and orange).

Each small table shows in column N the number of cooperating or defecting individuals within the firm. So in the top row blue table, there are 20 cooperators and no defectors in that firm. The next column, P, shows the average payoff to each person from random interactions amongst other firm staff. In the top row, the blue table has an average personal payoff is 10 because all 20 staff are cooperators and every interaction with another cooperator in the firm gives a payoff of 10. The total firm (or group) payoff is in column G and is 200 in this instance (20 people getting a payoff of 10 each).

The next firm in the top row, in green, has within it 15 cooperating individuals and 5 defectors. The average personal payoff for the cooperators in that firm is 7.5 because they have a 1 in 4 chance of dealing with a defector, and a 3 in 4 chance of dealing with another cooperator. The defectors have a higher personal payoff of 12.5 for the same reason.

Moving across the top row, the yellow firm has 10 cooperators and 10 defectors. This firm is a nasty place to be, and half the time, the firm is busy with staff blaming each other and not producing efficiently. The payoff (or total efficiency) for the firm is much lower, at a total of 150.

The last orange firm is mostly defectors, perhaps an extreme version of our Amazon example. The total payoff for this firm is just 125.

Outside these tables on the right side is a column N, which is the sum total of the number of people who are cooperators or defectors in each time period. In time one (the top row), there are 50 cooperators amongst the firms (20 in blue, 15 in green, 10 in yellow, and 5 in orange), and 30 defectors.

Moving from time one to time two, or going down a row, is a selection stage in the competitive evolutionary game of market competition amongst firms. That is, only the most efficient firms survive, and the least efficient die off from lack of customers from their poor value products made inefficiently. In fact, in this example, the most efficient firm expands to take up the market niche left by the firm that dies off.

So when we move to the second row in time two, the least efficient orange firm has died off, and the most efficient blue firm has expanded to satisfy that market niche.

But notice this. When we add up the total cooperators and defectors working in all the firms in the market at time two, there are now 65 cooperators (15 extra), and 15 defectors (15 less), compared to time one.

Competition at the firm level has led to the selection of the most internally cooperative and hence efficient firms, not the most internally competitive.

Going down one more row shows the new, relatively least efficient yellow firm also dies off. What worked at one point in time for them, when the environment was full of firms less cooperative than them, does not work at all points in time. Success in this evolutionary process is always relative to other firms in the market environment.

What is the result of this process?

We end up with firms that are highly cooperative and internally efficient, resulting in profitability. It looks like they are profit maximising. But they could have many alternative internal objectives, such as market share, cost minimisation, or quality maximisation. Whatever those firm objectives are, if they result in more internal cooperation, leading to efficiency and profitability, then they survive.

Another insight is that competition provides benefits when it acts as a selection mechanism that favours cooperative and efficient groups (or firms) that enable total production to expand. Variations that improve efficiency and cooperation within firms will, over time, be selected for by consumer choices in the market.

But what if competition happens within firms? What if individuals were truly competitive all the time?

Within-firm competition and monopoly

When there is a lack of competition between firms, the selection pressure arises within firms. This is common within government departments, which are monopolies and do not face selection pressures externally.

To illustrate the problem with competition within firms, let us think about the scenario of a large firm with multiple departments making multiple products for a variety of different customers. We can also think of large bureaucracies in general, such as government departments.

Perhaps the above example has led you to think that competition within company departments might be a good way to select the best ones.

Unfortunately, this approach has a huge incentive problem. The relative success of one department might be due to passing off costs to, or sabotaging, another. Within-firm competition that results in an evolutionary selection process is very risky, and it is well known that ‘silos’ in firms can result in conflict between what is best for each silo and what is best for the firm.

Unfortunately on most occasions, silos encourage behaviours that are beneficial to the occupants of the silo, but are often not in the best interest of the overall business or its customers. It also plays into the hands of corporate politics, since silos help to keep things private. And we all know that in office politics information is power. A recent survey from the American Management Association showed that 83% of executives said that silos existed in their companies and that 97% think they have a negative effect. (Source)

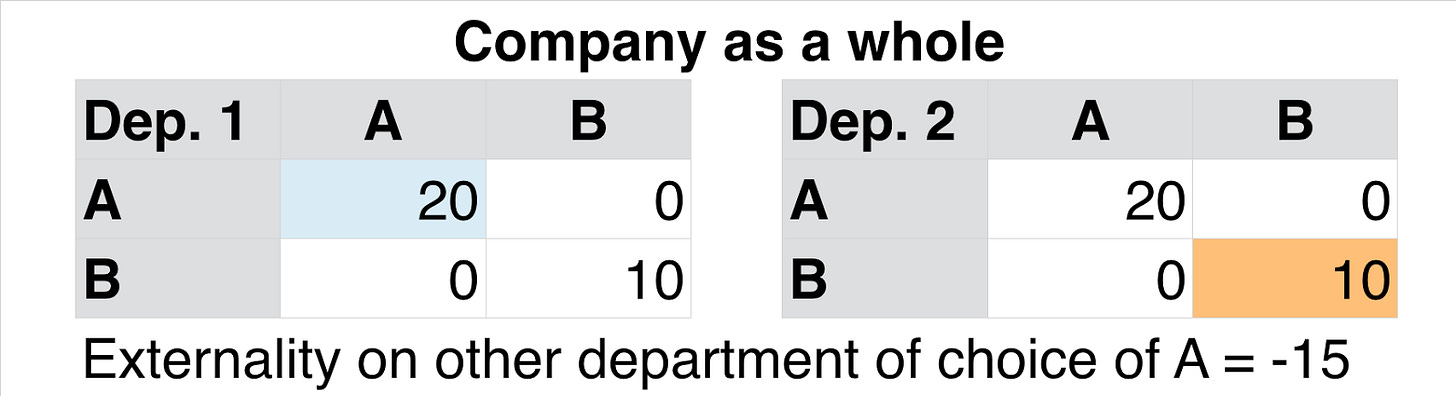

I capture the idea of relative competition within firms, which can include sabotage or passing on external costs to other departments, in the table below.

Here, the company has two departments (each small table labelled Dep. 1 and Dep. 2), and within each department, there is a choice to cooperate on either project A, which provides that department with a payoff of 20, or project B, which provides a payoff to that department of 10. However, project A comes with an external cost to the other department of 15.

For each department, it is better to cooperate on A, giving them 20 each, but also inflicting an external cost of 15 each. The overall company payoff is just 10 in this situation. However, if the departments each cooperate internally on B, the overall firm payoff is double, at 20, as there are no other externalised costs.

Thus, for large organisations, the emergence of silos that are blind to the situation of other parts of the company may end up with a choice of projects and investments that are not overall optimal and efficient.

Companies that find ways to ensure they maintain this inter-departmental efficiency as they grow are those that the market will select for.

Notice that this problem is a much more serious one in governments where there is no government-level selection pressure. At best, there is an occasional change of government in a democracy, but rarely does this provide strong incentives to change operational processes all that much.

Indeed, the incentive to sabotage other groups and inflict costs on them also arises with market competition in general, which is why competition laws and market regulations to minimise such negative external costs are so important to harness competition for the broader public benefit.

What about the chickens?

A model of a competitive selection process for cooperative firms provides more clarity about what economists mean when they speak of the benefits of competition.

Rather than simple models of competition being about the number of firms producing similar products, it shows that the underlying process of eliminating underperforming firms so that better-performing ones flourish. This process is open to competition by any means, whether internal production methods or by satisfying consumer demands with new products and services.

I don’t think there is a major contradiction between the mainstream economic view and the evolutionary view about the role and benefits of competition. It is just that competition is a black-box in simple standard models, with a few ideas added on in an ad hoc way, as is the existence of firms that themselves use internal low-cost cooperation methods.

Consider how a simple economic approach, that all competition is good, would inform the chicken breeding experiments of William Muir.

Muir bred chickens and either selected for a) the most productive individual egg-laying chicken, or b) the most productive cage of egg-laying chickens (in each cage were nine chickens).

The first method favored the nastiest hens who achieved their productivity by suppressing the productivity of other hens. After six generations, Muir had produced a nation of psychopaths, who plucked and murdered each other in their incessant attacks. No wonder egg productivity plummeted!

In the second approach, he selected the most productive groups and because they were already a group that worked well together, they included peaceful and cooperative hens. (Source)

Egg production by the cooperative cages increased 160% over just a few generations (more detail here). His results demonstrate that group selection is a process that increases the number of cooperators and total efficiency, whereas individual competition undermines the benefits of cooperation.

Could standard economic models of competition predict this? I don’t think so. A multilevel evolutionary approach sheds much more light on the process of competition.

Please share your thoughts below.

As always, please like, share, comment, and subscribe. Thanks for your support. You can find Fresh Economic Thinking on YouTube, Spotify, and Apple Podcasts.

Interested in learning more? Fresh Economic Thinking runs in-person and online workshops to help your organisation dig into the economic issues you face and learn powerful insights.

With the giant caveat that I am not an economist nor a biologist I do have some points I wanted to raise about your piece particularly around when selection can work. I know way more biology then I do economics so I will stick to that.

- Your Process A vs Process B seems a little simplistic. Surely the default assumption is that the firms are at best rational in a bounded sense facing a stochastic environment?

- It is really important to highlight when selection can work. If the environment is low dimensional with fast feedback and (reasonably) stable environment then evolution can work really well over short time spans. If the environment is not those things then it be either very time consuming or impossible for evolution to work!

- to give an example that is neither biological or related to economics you can look at the Deepseek paper from last year. While the markets viewed this as something of a referendum on Nvidia, the interesting part for practitioners was that the paper uses reinforcement learning directly to fine-tune the model. A year later and in practice generally people still do the start of that reinforcement learning with hand labelled results before switching to pure reinforcement learning. The reason is that the search space is so vast you can wait a long time for the model to build up momentum.

- David Sloan Wilson is a respected biologist but its important to note his views are very much in the minority and group level adaptations can almost always be explained from the gene-level. As I will discuss below in more detail there are very tight parameters required to make true multi-level selection work which almost never hold in the real world.

- Let's take your bee example as a way to to look at this. You mention that the selection is happening at the hive level. However the standard view of biology is that the reason the hive is coherent is that the worker bees are more related to their sisters (the other offspring of the queen) then they would be to their own offspring - due to the very different haplodiploid genetics of Hymenoptera. Helping the queen maximises the worker's inclusive fitness. This is known as Hamilton's rule after the late British biologist and is written as rB>C where r is relatedness, B is the benefit to the recipient and C is the cost to the actor. This is dominant view of eusociality in biology. We could just as easily talk about the cells of our own body which share identical DNA so there is no within-group selection pressure to defect. (When it fails you get cancer).

- For Group selection to dominate individual selection you need

1. High between-group variance in fitness (groups must differ substantially)

2. Low within-group variance (individuals within groups must be similiar)

3. Low migration between groups (or between-group varience gets homogenised)

4. Frequent group extinction and replacement (or selection pressure is too slow)

(see the work of George Price who lived a very weird life and after his seminal work on the Price equation gave away all his belongings and went a bit mad).

If you read Wilson his main cases are human group selection - like religious communes - which required extraordinary suppression of within-group competition which companies could never ethically achieve.

To show the brittleness I will share a link at the bottom to a github repo and some code that simulates the above. In short it only works when within-group selection is really weak. Claude knocked this out for me but you could easily write more complex scenarios if you wish.

- The other important factor is genetic drift. You talk in your piece about how the economy or evolution "select" the best performing business or organism. This is true on average, but again in the real world if we have small populations or weak selective pressures. There is always a chance that random chance swamps what is objectivly a better orgnism or business. (See the work on "neutral theory" originally by Kimura). I have included some small code at the github link below that highlights this.

- Finally I would say that there are a lot of economists who look at economics through an evolutionary lense (and vice versa). Jason Collins is an Australian researcher with a great blog (https://www.jasoncollins.blog/). Oded Galor, Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis are all economists who have used biology in their economics work. I also recommend Boyd and Richerson who are anthropologists but have some great books and papers on cultural evolution which shows how culture can impact human biological evolution.

A much nicer version co-written with Claude with python code and graphs is available at my github here: https://github.com/srepho/evolutionary-selection-economics

Please take a look at Axelrod’s experiments on cooperative competition where fair competition produces the best outcomes

Exactly the opposite of so called competitive money markets that are probably the most inefficient markets we could invent