Housing supply and the planning pipeline

Some new data and scenarios that need to fit your model of housing supply

Thank you to the 2,800 subscribers who enjoy Fresh Economic Thinking.

I want to ask a small favour. If you enjoy these articles, the best thing you can do to support me is to share them on your social media and forward the emails to your friends.

And don’t forget to subscribe. It’s free after all.

I have argued many times that planning regulations governing where different sorts of buildings and uses can be located are not causing high home prices and rents.

I have written many articles and research papers about this.

To be clear, my position is NOT that we shouldn’t have more housing. More housing is better than less housing. So we should build more new homes.

I think we should have more of everything. That’s what material economic progress is.

But we aren’t going to get more housing than we are getting if we let the market rip and remove planning controls because the market is already ripping.

If we want more homes and lower prices, we need a non-market actor to build them and sell or rent them at a cheaper price.

One of the problems I’ve faced making this case is that it is very easy for those arguing the opposite case to find high-profile battles with councils over new housing density in certain projects and give the impression that these battles are causing fewer homes to be built.

The solution of course is to look at the data. However, planning approvals data and the quantification of zoned capacity can be limited.

To contribute to improving the debate, here are some recent data and anecdotes that make my case. If you argue that zoning is limiting supply, then your theory of how housing is supplied needs to make sense of it all.

South East Queensland land supply

First, there are some surprisingly large numbers here in South East Queensland on the amount of zoned land. For industrial land, Ipswich Council has 672 years of capacity!

These are always underestimated. Back in 2003 similar estimates said Brisbane would be out of land in 20 years. Now, 20 years later, there are still decades of supply!

Western Australia

Here is some data showing enough zoned land in Perth and its surrounds to last three to six decades’ by conservative estimates, but this hasn’t stopped the recent rental price boom.

Greater Sydney

Planning approvals data in New South Wales started being collected two years ago when a central lodgement system was made compulsory for councils.

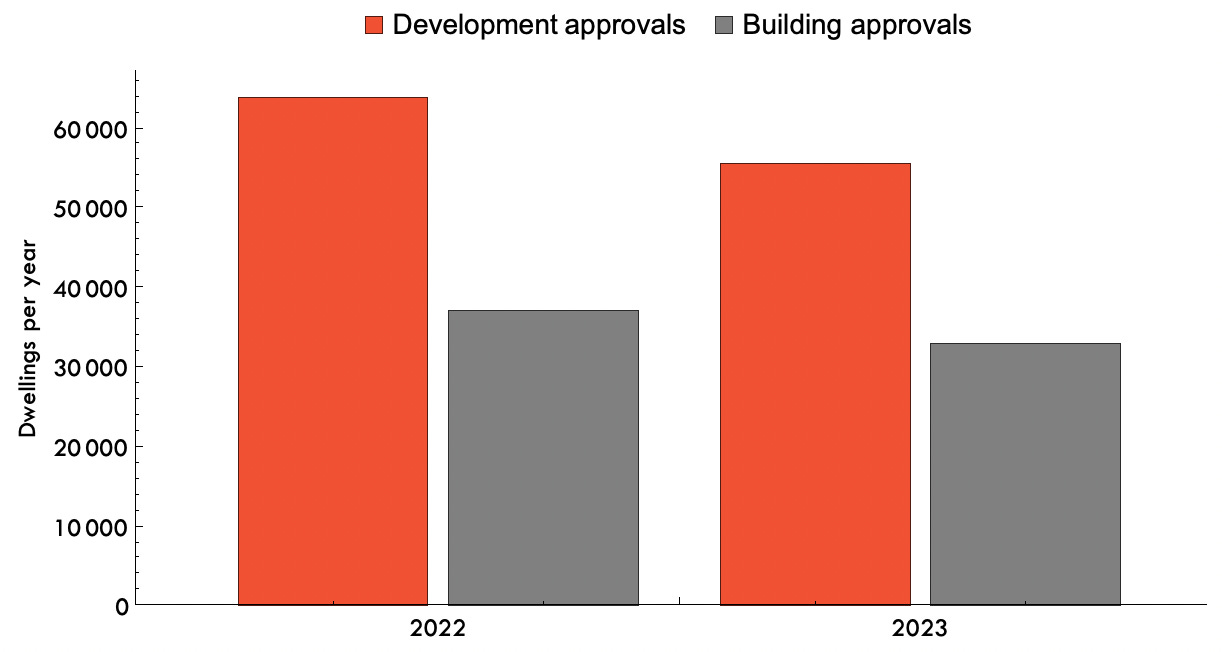

The data from this system shows that in FY2022 there were over 60,000 dwellings in projects granted planning approval. However, there were only about 35,000 dwellings in projects granted building approval. Extrapolating the FY2023 data up to April shows a similarly large excess of planning approvals over building approvals, indicating the build-up of a buffer stock of approved housing projects.

40-year-old planning approvals

It was recently reported that there are ‘zombie’ planning approvals in New South Wales that are now finally being developed after 30 years. Yes, those 1993 development approvals are now commencing construction in 2023.

As demand for housing reaches crisis point and land values soar, developments that had laid dormant for years in the New South Wales mid-north coast town are now being revived.

The latest to recommence was approved in 1993. And due to a gap in regulation, it only has to adhere to the environment and planning standards of 30 years ago.

“We understand there’s a housing crisis but the issue is that these DAs [development approvals] don’t really have an expiration date and can literally be this old and not have to pass the test under the current legislation,” says Kennedy, who is president of a community group advocating on the issue.

“Zombie DAs”, as they have been dubbed, have become an issue along the NSW coast, where incoming residents can be surprised to learn nearby patches of coastal bushland had residential developments approved years ago. As more works begin, many are now calling on the state government to step in and require developments to meet modern environmental and planning standards.

…

Further up the coast in Coila Lake, residents have been advocating against a DA approved in 1983 to develop 60 residential buildings.

Imagine in 1983 lobbying for this council to approve this project to increase housing supply and make rents cheaper, only for the project to be canned by the owner for four decades.

Any theory of housing supply must be able to account for these outcomes. Mine does.

The city that tried to force more density

In Wyndham, west of Melbourne, the council refused a planning application because it lacked density. After all, it is located next to the site of a planned new railway station. The decision was subsequently referred to the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal as the developer wanted to push ahead with fewer dwellings.

How do we explain this?

Delays due to market conditions

It has been reported that the approved and 80% pre-sold Oria apartments at Spring Hill were ‘mothballed’ recently due to conditions in the construction market.

How are we meant to let the market rip and get more homes if a mostly-presold building cannot get out of the ground?

Could you perhaps do a post comparing and contrasting the housing market to markets for other goods where fierce competition actually does push down prices?

For example:

- flatscreen TVs, which originally cost $20k and can now be found at Aldi for $200. Where advancements in screen technology permitted constant cost cutting, and no gov-granted monopoly barriers to entry exist

- the avocado market where we’re now hearing about a glut, also where competition can’t isn’t blocked by licensing or protectionism

Additionally, you’ve articulated when property owners naturally behave collusively to set the “speed limit” on new properties entering the market.

Could you perhaps explain when that behaviour could break down, like in severe economic downturn or banking system collapse like those seen in Japan, Ireland or Detroit?

Aggressively taxing land that is zoned residential, purchased, but sitting untouched for a length of time (say, a year) seems like an obvious starting point.

Allow a single block exception for individuals.