Economic lessons from Freedom's Forge

What lessons are there for economic development from the stories of the businessmen who orchestrated the wartime production build-up in Arthur Herman's book Freedom's Forge?

One of the big mysteries in economics is how countries become rich.

There are plenty of theories and stories out there— “it’s the magic of capitalism”, “it’s technology”, or more honestly, “it’s the unexplained residual.”

I want to share a glimpse of the economic development story in Arthur Herman's book Freedom’s Forge. This book is an extremely detailed documentation of the story of the key personalities, policies, and business decisions during the wartime economic build-up that massively increased the United States' economic capacity and wealth.

This is not a book review. I recommend reading the book yourself, but you might consider this review or this great Twitter thread by Misha Saul.

I want to connect the dots about the economics and the industrial policy options for rapid growth and trasnformation with the stories of the key businessmen and their trials and tribulations in the wartime build-up told in Freedom’s Forge.

The economic outcomes of wartime

Let’s start with the astonishing economic production outcomes.

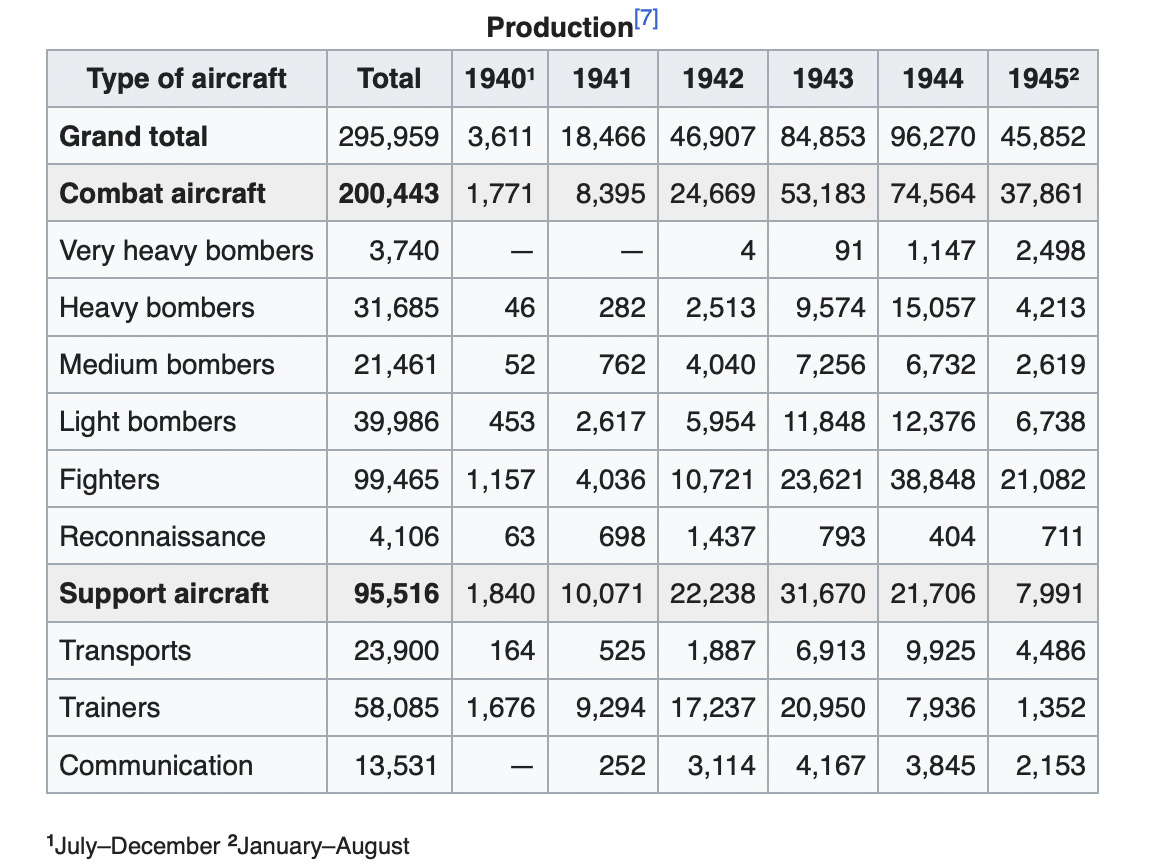

Here’s data from Wikipedia on United States aircraft production showing an astronomical 25x increase in total aircraft production in four years.

Similarly, the impressive scaling of mass production of merchant and navy ships also happened in this period (a good overview is here), increasing the output of ships by a factor of 20x to 50x over four years (depending on the type).

These were rapid expansions of enormous parts of the whole economy. Some of the figures in the book are hard to believe on first reading, but they match a variety of other sources.

How did this expansion happen so quickly?

Could other nations adopt similar policies and increase their non-military manufacturing output by such large multiples in just a few years by copying the U.S. policy stance of this era?

Let’s take a look.

The macro story

The first important detail to remember about the WWII build-up period was the enormous underutilisation of industrial capacity across the United States. As Herman notes in the book:

In 1939 the American steel industry was at its lowest capacity in twenty years.

President Roosevelt’s New Deal projects had been ramping up throughout the 1930s, building major public works and fostering state capacity for managing and coordinating major projects. Yet even still, total industrial output did not exceed 1929 levels, as the below chart shows.

Any economic policy lessons from this period must remember the context of the momentum of post-depression expansion, following a previous macrocycle that involved enormous technological leaps in mass production.

But this doesn’t help explain a 25x increase in output of complex capital equipment like aircraft and ships in just four years, alongside the vast array of associated production inputs to them (such as steel and metal alloys, rubber, oil, and so forth).

New Deal projects already attempted spending to kick-start activity. Was it just the scale of defence spending relative to the New Deal that made a difference? Or are there other hidden but important lessons that countries trying to industrialise can observe?

State-funded, privately organised, development

The scale of public spending of course mattered. You can see just how transformational this spending was, even relative to the New Deal, with over a third of total economic activity diverted into the military build-up.

The basic model of how that spending was used productively is quite standard in non-military development—state funding of privately organised capital investment and production.

But I think the most interesting part is hidden in the details of how the spending was directed to reorganise production.

Here are the big economic lessons for growth that I saw in the stories told in Freedom’s Forge.

Expertise sits within organisations that do the tasks (production knowledge is embedded in people and their organisations)

Adjacent industries can be entered by people and organisations with similar expertise when there is a clear motive to do so.

Economies of scale matter.

Discipline over deliverables matters—something for something, not something for nothing.

Embedded knowledge

The idea of embedded knowledge shines through in the stories told by Hermans. The main characters weren’t MBAs, but proven businessmen who had previously been through the hard slog of building up mass production facilities—Bill Knudsen, who “worked his way up from the shop floor to become the president of General Motors”, and Henry Kaiser, who built up a major civil construction company during the 1930s which even built the Hoover Dam. Or as Herman describes:

Knudsen knew how to make things, especially out of metal. Kaiser know how to build.

The same lesson of capitalising on the embedded knowledge of experienced people applies to any country, state, or region looking to change its economy today.

The United States has, for example, recently subsidised domestic microchip manufacturing. The actual operations and management of these investments have been done by foreign companies and their personnel with the embedded knowledge and experience to get it done without all the costs that come from learning those lessons the first time.

Adjacent industries

Sometimes, however, the desired investment and production are new and different from what had come before. The United States built very few aircraft in general before the build-up and few of the type needed to enter the war.

No one could be called upon who had the specific embedded knowledge for this task.

To the wartime planners and engineers of the day, it seemed clear that the production methods required were similar to those in the motor vehicle industry. Hence when Bill Knudsen moved from mass-producing motor vehicles on production lines to mass-producing aircraft production lines, he could still take a lot of embedded knowledge with him as he adapted the blueprints and designs from the British and French to local mass-production techniques in which he was fully experienced.

This is a common problem for countries trying to develop today. Often there is a political desire to skip over basic manufacturing to more high-tech production. But what adjacent industries will expertise be drawn from in this case? This can only work if people and equipment are imported whole hog.

Economies of scale

Another important lesson is that the types of production being paid for with public funds in the wartime buildup were those that had large economies of scale. This was not a case of duplicating infrastructure or building more new roads and dams with ever-decreasing returns per dollar spent.

This matters long term as the construction of, and production from, these wartime facilities led to a broad build-up of expertise in mass production techniques which would become broadly applied in the post-war period.

And it is the expansion of industries with economies of scale that helps create robust growth.

Discipline

As you might expect, spending a third of GDP on public procurement of military hardware from private firms comes with a great deal of corruption risk.

There is a tricky balance.

To get the people and firms with the embedded knowledge of how to do the required task means offering them an economic return that exceeded what they could get elsewhere.

But how much more? And how do you ensure that they come through with the goods?

As Herman explains, previous war experience had led to tight rules to combat profiteering from public military contracts. But some of these rules were too tight for the new situation.

Starting in 1933, congressional legislation had placed sharp restrictions on how much war suppliers could make on their government contracts. During the First World War, cost-plus contracts were common, meaning that the government would pay all expenses relating to making an airplane or artillery gun, in addition to a fixed fee or percentage of cost-8 percent was fairly standard. The postwar reaction against "war profiteers" led Congress and the Treasury Department to impose sharp curbs on the profit companies could make on orders larger than $25,000. They also required an advance audit to guarantee that the company's profit would be no more than 8 percent even before the contract was signed.

In addition, every government contract for a new airplane or tank or vehicle required bidding companies to pay for the production of their prototype and the new machine tools to manufacture it. No money was ever advanced, even to the winner of the bid. As one executive from Boeing put it, "There was no sound of coin in Uncle Sam's jeans." An aircraft maker looked at an average of a half-million-dollar investment just to enter a bid -with no guarantee of winning. Even if he did and problems or delays developed, the government was not above pulling the contract, leaving the company high and dry.

The same tricky problems happen today.

This is why governments will often need to adopt contracts that share risks in situations where large capital outlays come with large risks, either in joint ventures, public-private partnerships, or other arrangements.

Back then, the trick was to change tax laws to allow capital spending to be quickly deducted. The 16-year amortization rules wouldn’t make sense, since the production facilities might get 16 years of production, with all the production happening in the first few years and hopefully the war being over.

Then there were the tax laws. Every American company's investment in new plant construction, tools, and other physical resources necessary to produce a plane or tank or aircraft, even with a contract, took sixteen years in order to be fully deducted as a business expense.

Knudsen saw at once that these amortization rules (Knudsen had to get John Biggers to explain to the president and Cabinet what amortization meant) made the short-term investment in plant, property, and equipment necessary for the defense buildup almost impossible.

"Mr. President," Knudsen said, "do you want statistics, or do you want guns?" If the latter, he explained, then amortization should be drastically shortened to five or six years. Hitler's German companies, he pointed out, worked on a seven-year rule. Companies would get their investment back quicker, and be more willing to take risks on manufacturing things that had no commercial value to them but were crucial to the defense effort.

"The government can't do it all," Knudsen told Roosevelt. "The more people we can get into this program"—in other words by offering incentives instead of threats—"the more brains we can get into it, the better chance it will have to succeed"

This came with risks of exploitation of course. Most contracts were then granted on a cost plus 8 per cent basis, and this led to much political bickering over whether value was being received from these contracts.

"Why should the agencies of government in Washington today," said CIO chief Philip Murray, "be virtually infested with wealthy men who are supposedly receiving one-dollar-a-year compensation?" Such men were only using war mobilization to pad their old companies' profits and those of their cronies, the critics said. "Patriotism plus 8 percent," they called it, while others argued that the only way to overcome the conflict of interest was to create a British-style Ministry of Supply with complete powers over all wartime production.

Much of the discipline that led to these contracts working was the personal discipline of the key characters involved, who had to maintain face amongst their communities by delivering what was promised.

Less so was the discipline arising from the limited opportunities for government agencies to redirect spending elsewhere if outputs failed to be delivered.

These days, discipline in procurement comes from the opportunity to spend elsewhere. Perform poorly on one public contract and you won’t get another one.

One problem in modern military procurement is that there is often only one company with the expertise to build a product. So a trick being used now is to foster investment in start-up firms to build their expertise and to provide that discipline alongside potentially new and different products.

For nations trying to industrialise by subsidising local industries today, a common way to maintain discipline is by linking subsidies to export targets, which ensures that companies are investing in the quality of products that can compete in world markets. If they can’t, the subsidy is removed or reduced.

Whichever way it goes in practice, the point is that the private organisations you want to be involved in public investment need higher returns than elsewhere to undertake those projects, but to keep those projects they must be disciplined to ensure they deliver.

So what?

Freedom’s Forge to my eyes reads like an industrial policy economics textbook. It is amazing to see how these now well-established lessons of industrial played out and the sheer scale of the transformation that took place in the war years.

On the whole, you come to appreciate both the political pragmatism of the times and the deference to technical expertise, which ended up fitting with the current lessons of how the industrial transformation of economies comes about.

If you enjoyed this article you will probably also enjoy this conversation on the topic of industrial policy.

Mariana Mazzucato's books on the entrepreneurial state and on mission economy describe the NASA approach to the state getting stuff from/by private firms. Important to this seem to be that NASA retained the skills and knowledge to write effective contracts, including clauses about no excess profits. This has been lost with the dumbing down of the public sector and the rise of the managerialism assumption that an intimate knowledge of the industry being managed is not necessary.

This was interesting. But I’m a little wary of how much ww2 based economic development can serve as a guide for developing countries now. I’m thinks of how much social license they can get, willingness from private sector and basically that they don’t have the urgency of war. I feel like some of the stuff Kyle Chan talks about with China seems interesting and more doable https://www.high-capacity.com/p/managed-competition-in-chinas-state?utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web