Richard Tooth has a plan—save 300 lives a year on Australian roads. How? By using economic ideas to align risks and incentives better.

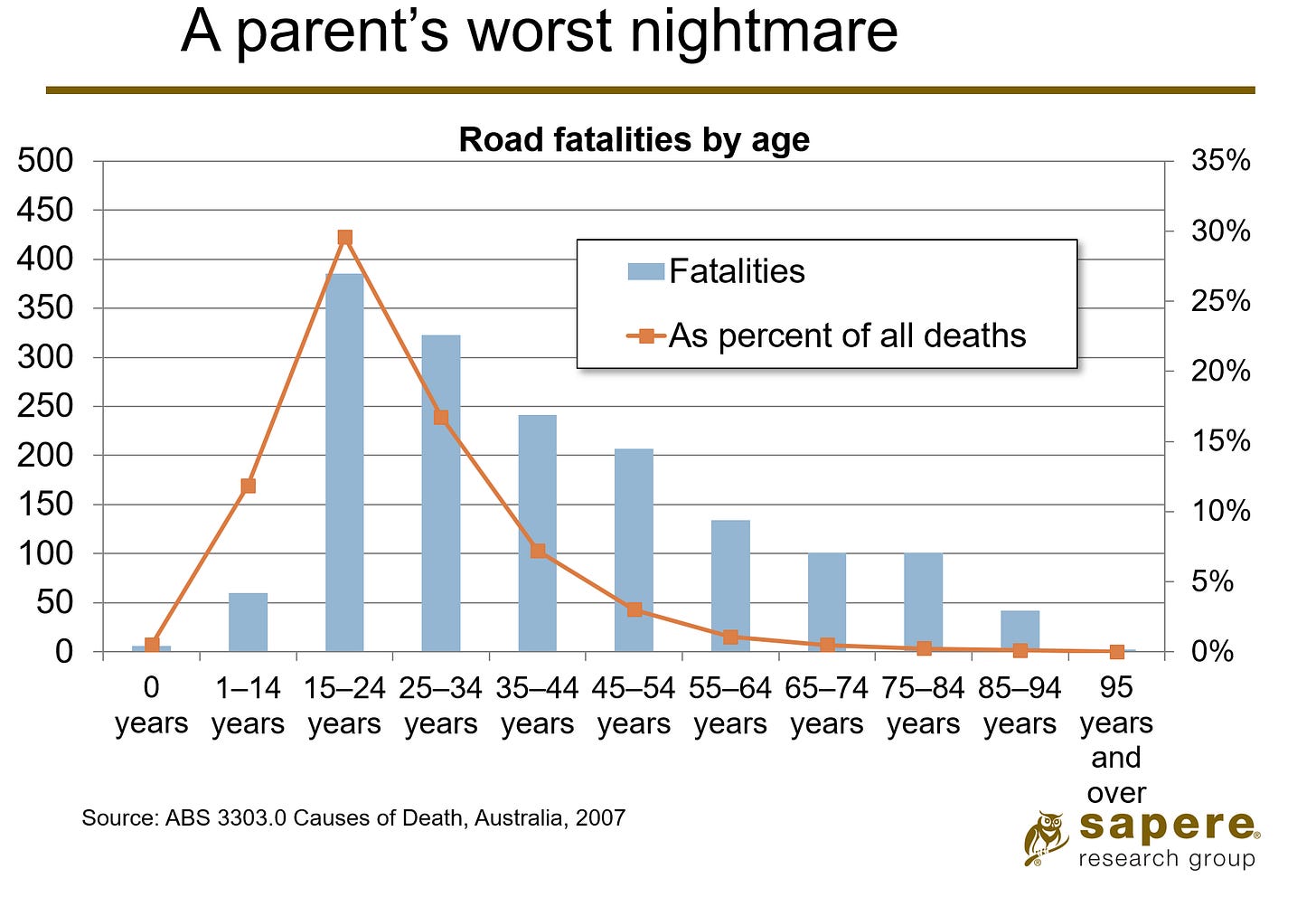

Take a look at the chart below.

People who die on Australia’s roads are young. Preventing a road death would save 40-50 years of life on average. That’s big. Cancer treatments typically save 4-10 life years, then we get five to ten times the life gains from preventing a road death as many deaths from diseases.

I learnt from Richard that people will change their behaviour on the roads, either by driving more carefully, choosing a safer vehicle, or choosing not to drive at all, given the incentive to do so.

But how to improve people’s incentives?

Richard argues we can do this by changing how we regulate insurers. Give the insurers the right incentives for road-safety and they’ll encourage people to make better safer choices.

And it works.

He points out that relative to Australia insurers in the United Kingdom have greater – but still not optimal - incentives for road safety. In the United Kingdom insurers try to save money on payouts by offering discounted vehicle insurance to young drivers who opt in to telematics, a tool on your vehicle or phone that tracks your driving behaviour (braking, speed, acceleration, etc), which changes behaviour and only the whole reduces risks for all road users.

Here’s a working paper of Richard’s about changing the way insurance functions to align the incentive of insurers with reducing road injuries and fatalities, using the insurance relationship to incentivise safer driving choices.

It makes sense. Although I sometimes wonder whether such marginal changes make big differences, the fact that risk on the roads is heavily skewed by age and across people means that such incentives can have tangible effects on aggregate risks by focussing on those key people.

To give a sense of the scale of the benefits, Richard reckons that such incentive changes through insurance could reduce the road toll in the range of 20% to 40%, saving 300 lives of the 1,300 lives taken on the roads each year and preventing a similar proportion of the 40,000 road injuries.

In all, he reckons there are about $20 billion of benefits from better incentives to reduce overall road risks, while the cost of these changes would be extremely low.

If you have an interest in this policy area, please reach out and I can put you in touch with Richard.

For those who want to dig more into the topics we discussed, try these links

The 2021-22 Parliamentary Inquiry into Road Safety. Note its the

Committee’s Recommendation 26:The committee recommends that the Australian Government work with state and territory governments, the insurance industry and other road safety stakeholders to investigate opportunities to reform motor vehicle insurance and to develop a roadmap towards policy and law reform.

The Government responded in October 2023.

The Australian Government will raise this recommendation with the state and territory governments, who are responsible for compulsory third-party insurance.

The Bureau of Infrastructure and Transport Research Economics (BITRE) publishes an annual report that compares Australia's road safety performance with that of other OECD nations. Find it here. The BITRE also reports on the social cost of road crashes, and you can find that here.

We spoke of the Tullock Spike and how decreasing risks for drivers in the road makes them behave in a way that increases the risks for others. This article on the Peltzman Effect describes the incentives at play.

As always, please like, share, comment, and subscribe. Thanks for your support. Find Fresh Economic Thinking on YouTube, Spotify, and Apple Podcasts.