Do medical school entrance tests constrain supply?

If we can work this out, maybe we can work out if town planning constrains housing supply

The GAMSAT is an entrance test that all prospective students to medical schools in Australia must take.

I want to use a hypothetical scenario about this test to understand how it might be possible to determine whether it constrains the rate at which new doctors are trained.

The hypothetical

Some people say that this test affects the total stock of doctors and hence the price of medical services.

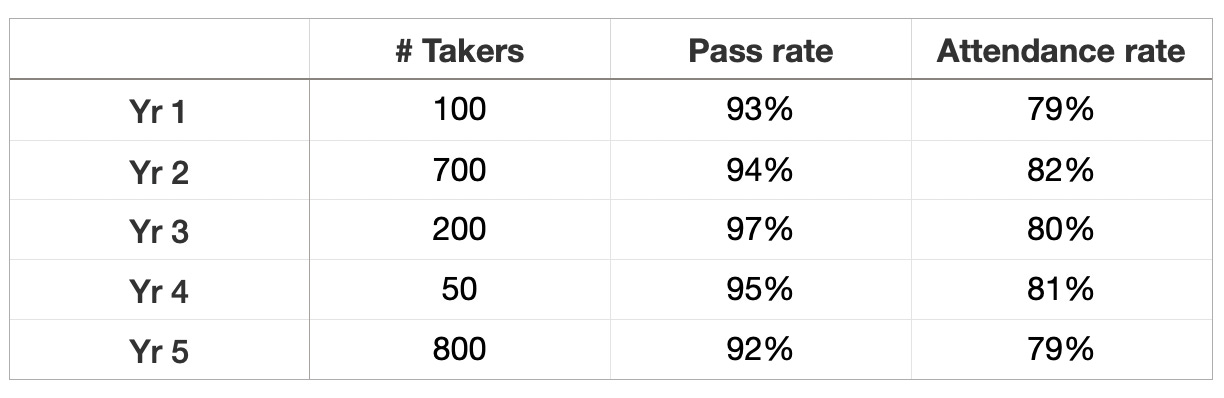

You have the following information and are asked whether this is a potentially important concern.

In addition, you know that

Only those with a bachelors degree are eligible to take the test.

The number of people graduating with bachelors degrees each year is nearly a consistent 20,000 per year, adding to a large pool of candidate test takers.

Those who do not pass the GAMSAT can re-sit the test as many times as they like in subsequent years.

Those who pass have the option, but no obligation, to attend medical school.

You must re-sit the test if you do not go on to medical school within three years.

100% of those that decide to attend medical school complete it and become practising doctors.

You are asked to advise whether the pass rate contains information about the degree to which the entrance test determines the stock of practising doctors. Some say the high pass rate and ability to re-sit the test shows that the GAMSAT test is not a constraint on the supply of doctors.

Let us think this through.

The system perspective

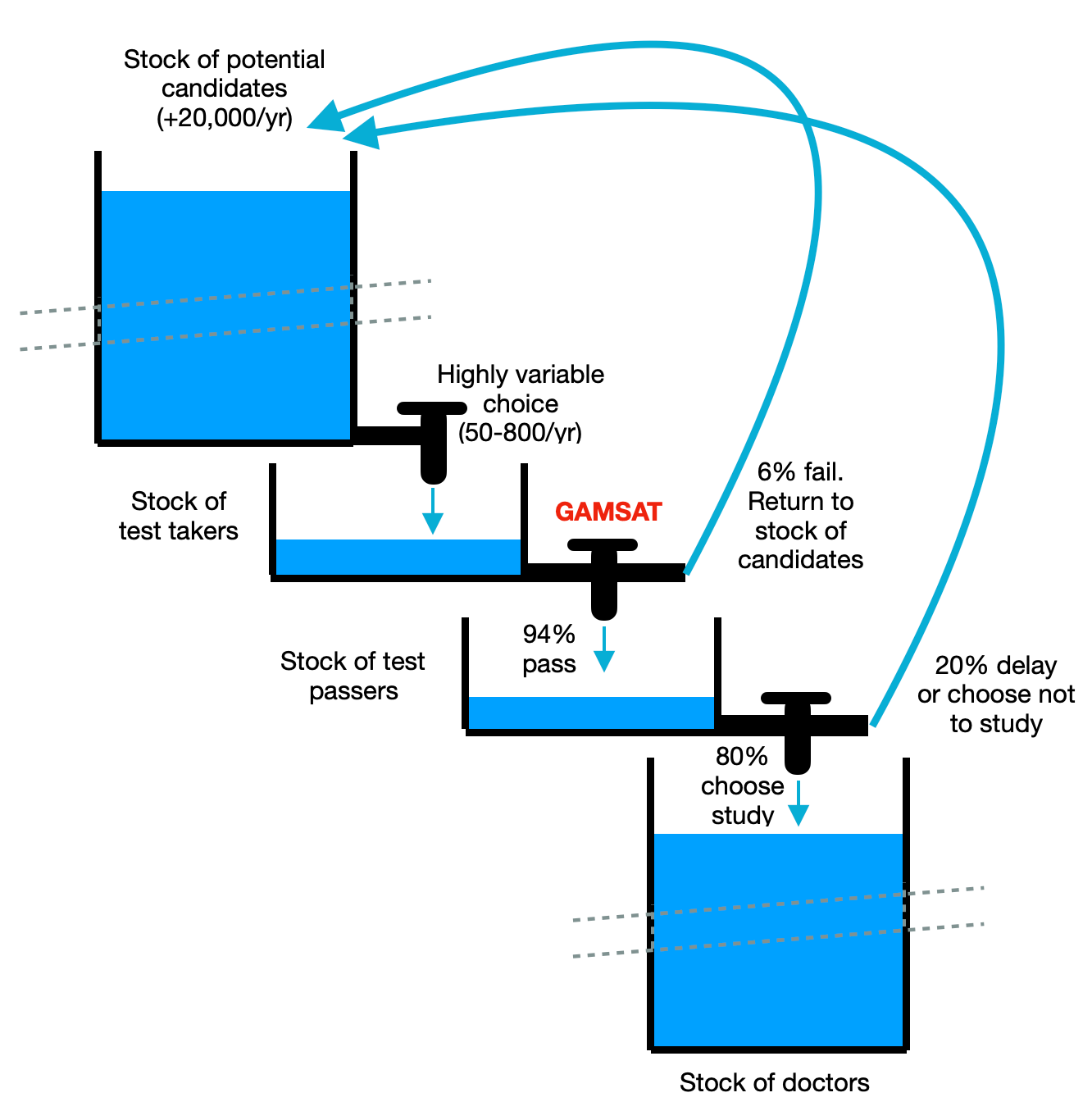

The first thing to do is get a good understanding of the system with the numbers involved. The below diagram shows how the stock of potential candidates flows through the testing system to become doctors. There are three decision points.

The choice to take the GAMSAT test

The pass/fail choice

The choice to proceed to study after a pass

I draw these choices as taps that control the flow of “water” into the “buckets” (stocks of people at each stage). Notice that two of the choices return the people back to the pool of candidates—the pass/fail, and the study/delay choices.

Quite clearly the most important choice in getting water from the stock of potentials to the stock of doctors is the choice to sit the GAMSAT test in the first place.

This choice has by far the biggest effect on the outcome, with its variability accounting for the variation of flows through the system by a magnitude of 16x. One year 50 people took the test. One year it was 800.

None of this variation appears due to the GAMSAT test as the pass rate is unchanged and the choice to proceed is unchanged (we will return to this assumption).

By looking at the system in this way we can see that the maximum amount of additional doctors getting through the process by removing the GAMSAT test is 6%. It is likely to be less than this because those who fail often repeat the test.

You conclude that the GAMSAT test is at most an extremely minor factor influencing the rate of supply of new doctors.

A new argument

However, some argue that there is no evidence in the 94% pass rate that the GAMSAT is not a major constraint.

The argument is that the existence of the test reduces the number of applicants. Those who are likely to fail will know in advance and choose not to take the test. Therefore, even if the pass rate was 100% the GAMSAT could still be a major restriction on the flow of new doctors. It might be a plausible assumption that the variation in the choice to sit the test is explained by the number of people who believe they will pass it.

So we have two potential mechanisms of actions of the GAMSAT test.

A direct effect due to the pass rate

An indirect effect due to reducing the number who choose to take the test

How could we tell if the second mechanism was important?

We could look further up the system and see if the variability of the choice to take the test is related to factors regarding the test stringency, or other factors. But how would you measure test stringency if not for the pass rate?

You would need a third variable that measures test stringency that is unrelated to the pass rate, and that correlates closely with the number of test-takers. Possible? I’m not sure.

The problem is that if the second indirect effect dominates, then what are we to make of variation in the pass rate? What if a 10% pass rate is the norm, and that falls to 5% when the number of test-takers is high? This would surely indicate that the indirect effect is minimal and that people do not have a good idea of whether they will pass in advance. Or that they are willing to take the chance even if they have a good idea in advances.

Whichever way you cut it, the presence of an indirect effect surely must show up in the pass rate to some degree.

What have we learned?

It seems logical that there is information in the pass rate about the degree to which the GAMSAT test can reduce the flow of new doctors compared to if the test did not exist.

In the real world, and not the hypothetical I described, the pass rate for the GAMSAT is about 20-25%. In fact, the pass rate is itself determined by a quota on new university places. The test doesn’t constrain new doctors because the university quotas do it, and that quota determines the passing grade and hence the pass rate.

But this post is not about medical school. It is about town planning. The “entrance test” in the planning system is a planning application, which is required to (re)develop a property.

Many argue (e.g. point 4 here) that just because 90%+ of the planning applications are approved that this doesn’t indicate there is at most a small effect on the rate of new housing supply. They argue that the indirect effect dominates and that’s why the approval rate is high.

But this leaves us with a conundrum. We know that a property with a planning approval is worth a lot more than one without. Therefore there is a large payoff to getting an approval. Just like there is a large payoff to becoming a doctor.

Yet candidate medical students are willing to sit a test with a near 80% failure rate, often repeatedly, to get that payoff. However, property owners are not, even though the payoffs can be worth tens of millions of dollars or more.

While an indirect effect surely exists in both medical school entrance tests and town planning applications, the pass rate also contains information about the existence of this effect.