Deceptive debt burdens

“Our grandchildren will inherit the government's debts” is a common phrase. But it is wrong, and economists should point that out. But many still believe it.

The fact that many economists still think that government debts are a burden on future generations is a puzzle to me.

There is one right answer.

No.

There are two reasons for this, as I noted in this tweet.

The first is somewhat obvious. Every debt liability is another’s loan asset.

Your mortgage? Your debt liability and the bank’s loan asset. Government debt? The government’s debt liability and the bond holder’s loan asset.

Every debt comes with a corresponding asset. By definition.

That should be the end of it.

But even if you, for some reason, did not accept this, and still think that the cost of debt can be passed into the future, this would still not burden our grandchildren.

Because if the current generation can push burdens into the future, so can our grandchildren. We’ve discovered a magic time travelling solution to all our debt problems!

Modelling tricks

One of the ways people will “prove” that debts can be a burden for future generations is with an overlapping generations (OLG) model.

But the trick in this approach is that creditors and debtors get relabelled as “generations”. That’s how the rabbit is put in the hat.

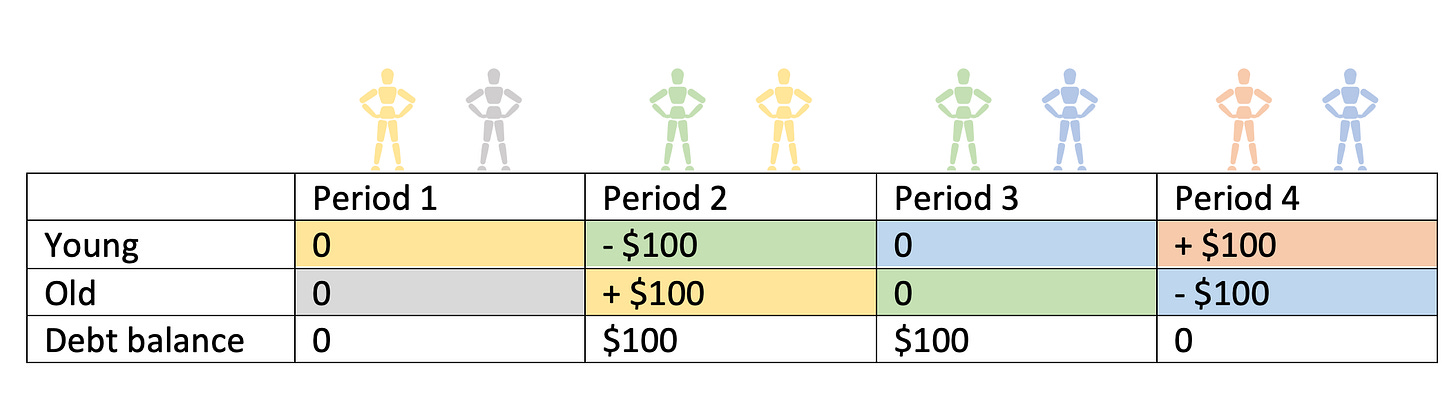

In the below table, I show the basics of the OLG model. In each period, two “generations” are alive, with each generation represented by a colour. The cells in the table are shaded with their colour (i.e. the yellow generation is young in Period 1 and old in Period 2).

The numbers in the cells in the table are the size of the net transfer that takes place between generations using debt. In Period 2, we show the government borrowing from the green young generation to give the old yellow generation $100, creating a debt balance of $100 that carries forward into the future.

Then, in Period 4, the government repays the debt by paying back the young from the old.

On balance, we can see that the yellow generation, that lived in Period 1 and Period 2, was able to consume $100 of extra goods over their lifetime because of the debt taken out in Period 2. The future blue generation, that lived in Periods 3 and 4, consumed $100 less in their lifetime because they repaid the debt when they were old in Period 4 that they did not incur.

So it seems like the debt taken out to give the yellow generation money cost the future blue generation that wasn’t even alive at the time.

But this is silly. In Period 2, there are creditors and debtors. In Period 4, debtors repay creditors. Generations don’t repay each other. Governments repay bondholders. Those bondholders will be the descendants of the green generation who gave up the resources initially to facilitate the debt (i.e. buy the bonds).

Why is the blue generation paying the red generation, neither of which was alive at the time of the debt being incurred? The red generation could just as easily repay the blue generation. After all, we are just arbitrarily assigning creditor and debtor roles to future “generations”.

We can also see in this simple model that the economic cost of the debt is paid when it is taken out. The green generation transfers resources to the yellow generation in Period 2. The transfer is complete. The debt transferred resources exactly at the time it was taken out.

Counting one side of the ledger

We know debt must transfer resources at the time, not push the resource cost into the future because debts are agreements that can be changed. We can write off debts. If debts could push the burden into the future, we should take out lots of debts and then write them off so as to never have to face that mythical future burden.

Another way to think about this is to ask the question “are financial assets a net benefit to future generations”? The answer here, again, is no. Because the asset is also a liability to others. That Treasury bond asset your grandchildren might end up owning? That’s a liability for the future Treasury. That Apple stock you own? Its value comes from the high profits from future customers, which is a cost (liability) to them.

As I’ve explained before, compulsory saving schemes intended to “pre-fund” retirement income systems don’t actually change the economic transfers involved. They suffer from the problem of merely counting one side of the ledger, the asset side, and ignoring the liability side. The idea of government debt being a future burden suffers from the same problem, but in reverse, of counting liabilities but not assets. And sometimes we trick ourselves into thinking otherwise by renaming creditors and debtors as “generations” in the OLG model.

I really enjoyed reading this and thinking about debt in this way. However, if our objective is to change thinking we need something much simpler than this. This explanation or argument is far too complex. We need to find simple analogies that people can use to relate their real-world experience to arguments about austerity, in a way that feels like common sense not a priori or logical reasoning.

I'm a hypocrite because I haven't developed a simpler story myself, but how about this possibility: I bought my house 15 years ago and the principal repayments were about 15% of my net income. (With interest it was like 40%) Before then my rent was about 20% of my income. Today the principal repayments are about 5% of my income. (With interest it's like 10%) This is what ACTUALLY happens. There is no way you could argue that I stole from my future self by taking on debt. Absolutely none. And the way it works with public debt and investment is way more profound an effect than this. I think as economists/academics we can get caught up in logic - logic is the way we should think but it isn't the way we should communicate.

Your starting assumption, that “[e]very debt liability is another’s loan asset”, is an accounting statement which contains a surprising truth when you analyze it carefully.

I need to describe the transaction preceding your statement so we can consider the financial positions of the two parties involved, i.e., the creditor (C) and the debtor (D), as their two balance sheets involve two sets of asset and liability accounts, one pair for each of them (i.e., 4 accounts in total).

In your article, you say that D has incurred a debt to C, so I’ll consider one example you cite where the new liability is a “bank mortgage”. In effect, that means the bank customer’s IOU was handed to the bank and received by it as a new bank asset.

What happens in the bank’s accounts?

Obviously, D’s IOU is recorded as a debit-item in the one of the bank’s asset accounts (in particular, the “loan account” opened in the name of the customer, D), increasing the bank’s total assets, represented as a debit-balance. That debit-item should be matched by a corresponding credit-item in a different account. Here there are two possibilities which you have not analyzed.

One possibility (a) is that the matching credit-item is posted to the bank’s CASH asset account, representing the withdrawal of the loan amount in CASH which was handed over as a loan to the customer.

The only other possibility (b) is that the matching credit-item is posted to a bank liability account, representing the fact that the bank still owes the customer the amount of the loan, the implication being that “payment” requires an asset transfer (i.e., CASH).

What happens in the customer’s accounts?

The amount of her IOU is obviously recorded as a credit-item in one of her liability accounts where it represents the increase in her total liabilities (shown as a credit-balance). That credit-item should be matched by a corresponding debit-item, representing what D received from the bank (C).

But where D posts that debit-item depends entirely on which of the two possibilities, (a) and (b) above, occurred at the bank.

If the bank paid out the loan amount in CASH, as in (a), the customer would post the debit-item to her own CASH asset account (where it will increase her debit-balance). But this never happens in practice.

What always happens in practice is (b). The bank records the fact that it still owes the customer the loan amount as a liability and does NOT pay out CASH. This fact is represented by a credit-item in one of the bank’s liability accounts (where it will increase the credit-balance). That account would also be one which must have been opened in the name of customer D.

This credit-balance is INDEED, the asset of customer D! So, she must post that matching debit-item to her “deposits at bank” asset account, recording that credit-balance in the bank’s liability account as her new asset. So, your starting assumption is correct: The customer’s asset is represented as the credit-item in the bank’s liability account.

But this proves the very strange FACT that the bank did not payout the loan! The FACT that it is still obliged to do so is represented by that credit-balance in its liability account.

Here begins the deception: When the bank C does not show D this bank-liability account, she remains unaware of this accounting deception and happily purchases whatever it was she intended to buy with the new “loan of credit”. She thus transfers “her credit” to another Unsuspecting person (U) who accepts her cheque. U deposits D’s cheque and “her credit” is transferred to U’s account at a different bank (Z).

Both banks, C and Z, know this game well and the originating bank (C) now happily owes U’s bank (Z) the amount of that “credit” until U demands a payout in CASH. The originating bank (C) can thus avoid paying out its debt-obligation indefinitely, as long as people (like U) accept cheque transfers of such “credit liabilities” of banks as an alternative to CASH.

Now do you see where criminal fraud comes into bank “lending”?

The bank C claims it is “lending” its customer D the credit-balance in an account which it opened in her name, when the same credit-balance is already her asset. Lawyers call this behaviour “conversion”, a nice legal term which means “theft”.

My accountant once summarized this argument for me in very simple terms as follows: “Nobody can lend a liability!”