A legacy of bad economics from Adam Smith’s Pin Factory

Did Smith learn the wrong lesson from his factory tours? And why do we keep reciting it uncritically?

Fresh Economic Thinking exists to elevate the quality of economic discussion. This is why I write detailed articles about influential economic ideas—I want to help progress the discipline. Please consider a paid subscription to support these efforts.

Like many well-trained economists, I took Adam Smith’s argument about productivity gains being caused by the division of labour at face value. It wasn’t until I read Joan Robinson dismiss the argument in her 1973 textbook An Introduction to Modern Economics that I began to put the effort into understanding the division of labour.

I realised it was an incoherent explanation for productivity gains.

But I also realised that the pin factory story could provide valuable lessons about economics nonetheless.

Robinson dismisses Smith by suggesting that people can equally divide their labour across different tasks through time. The 18 distinct operations Smith recounts at the pin factory could just as easily be conducted by the same labourer on 18 different days to generate the same output per person over 18 days as in the case where labour is divided between workers.

Further, the fact that relatively unskilled labour could perform any of these tasks adds to the case that it is not specialist skills from the division of labour at play in generating productivity gains.

One-way causality from the division of labour to productivity gains is a highly problematic story.

But that leaves open the question about the actual mechanism that provided the enormous productivity gains in the pin factories of the mid-1700s.

Instead of Smith’s division of labour hypothesis, let me propose a capital investment hypothesis to explain the productivity of his pin factory. This hypothesis suggests that it is the technical nature of capital that determines the way labour will be divided across tasks to maximise output and that the division of labour is a response to this capital investment. The causality goes from capital investment to labour division.

To guide my inquiry I use the structured approach I have described in the past for confronting economic issues by first asking questions about aggregation. For example, why are there 18 tasks to make a pin, not 5, 9, 16, or 37? Why are 18 workers in one pin factory and not 9 in one factory and 9 in another owned by a different entity?

The answer to these questions is capital.

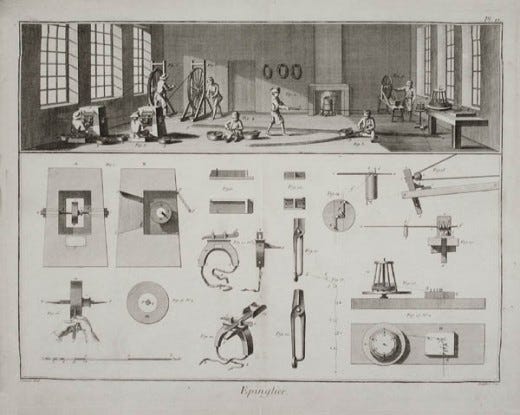

The image above shows the tools and equipment used in the pin factories described by Smith. Notice that the tools and machines in the picture have been designed to more efficiently perform distinct parts of the pin-making process. It is the way the tools have been designed to efficiently break down the task of making pins that leads to the labour division to man the tools.

Smith came close to instead presenting the capital investment hypothesis. He says

…a workman not educated to this business (which the division of labour has rendered a distinct trade), nor acquainted with the use of the machinery employed in it (to the invention of which the same division of labour has probably given occasion), could scarce, perhaps, with his utmost industry, make one pin in a day, and certainly could not make twenty. [my emphasis]

He suggests that the division of labour probably gave rise to the machines, rather than the machines themselves giving rise to the division of labour. This seems very strange to me.

And this logic comes undone later in the paragraph, even though he ignores the inconsistency in his argument.

…the important business of making a pin is, in this manner, divided into about eighteen distinct operations, which, in some manufactories, are all performed by distinct hands, though in others the same man will sometimes perform two or three of them. I have seen a small manufactory of this kind where ten men only were employed, and where some of them consequently performed two or three distinct operations. [my emphasis]

Even based on Smith’s observations it is the tools and machines that generate the 18 tasks. People can, and do, perform more than one of them. So how exactly did the division of labour give rise to the invention of the necessary machines that generate 18 tasks with only ten men?

If it was the division of labour that led to increased productivity, labour could just as easily be divided between firms. The fact that pin factories, even with only ten men, still performed all 18 tasks, instead of specialising in just 10 tasks, is clear evidence that there is something special and coordinated about the tasks themselves that arise from the particular capital investments. The tools and machines are designed to be compatible with each other, and if part of the process is done outside the firm, each of the two firms would inevitably be tied to the same compatible capital equipment, and would therefore find gains by merging into a single firm.

The next step in a structured inquiry is to ask questions about timing to see if we can more sharply distinguish between the division of labour and capital hypotheses. If it was only after the machines were introduced that labour was divided in a particular way, then that is evidence for the capital hypothesis. If labour was divided into 18 tasks before the investment in machines, achieving the same tasks in the absence of those specialist tools, then the division of labour hypothesis holds.

Quite clearly when we look at timing, the capital investment hypothesis comes out ahead.

The third and final step in our inquiry is to think about prediction. The capital investment hypothesis predicts that labour task specialisation can respond to capital investments in either direction—either with more division of labour or by adding to the tasks done by a single labourer.

A modern test of these predictions could be garbage collection. With rear-loading trucks, labour is divided between driving the truck and loading the bins. But with more advanced side-loading trucks with robotic arms, the labour is once again undivided between driving the truck and collecting the bins. The progression of capital technology determines the division of tasks.

The same would be true in the pin factory. If new tools were invented to get the same result with 5 steps instead of 18, that would be a huge efficiency gain but a major reversal of labour specialisation.

Where is the confusion arising?

What is strange to me is that increasing the number of possible production tasks in an economy means that each person does more tasks rather than fewer—the opposite of labour division.

Imagine a tribe of 50 people that can undertake 100 productive tasks. Then with the invention of new tools, the number of possible tasks the tribe can undertake expands to 150. The average tribe member is now doing three instead of two tasks each.

That doesn’t seem like labour division.

I think the confusion arises partly because of labelling conventions about roles in society rather than actual units of labour being devoted to fewer clearly defined tasks.

Here is a minimal example of mixing up socially-labelled productive roles (i.e. butcher, baker etc.) with actual tasks (baking, mixing, filleting etc.).

Inspired by stories about how the division of labour was part of early human tool-making in tribes of Jordan, my example is a six-person tribe that undertakes six defined tasks, of which the two named roles undertake three tasks each. Thinking in terms of roles there are three hunters and three gatherers. That is, two types of specialist.

But in terms of tasks, there are six tasks to be done. Each hunter must be able to track, kill and clean the game. Each gatherer must collect, prepare, and cook the fruits and vegetables.

You might want to argue that the way I define tasks is open to limitless ad hoc classifications. Tracking an animal could be further divided into a team pursuit with specific sub-tasks for each member. Same with cleaning an animal. But this is kind of the point. Any defined task will be a bundle of sub-tasks. But to understand the division of labour we need to keep track of tasks at any one particular level of aggregation and not fall into the trap of calling something specialisation when it is just a different bundling of more tasks into one job.

One of the tribe members now invents the spear and woomera. Regular production of these tools requires three additional tasks to be undertaken by the new toolmaker role in the tribe. One former hunter becomes a tool maker, and one former gatherer becomes a tool maker.

Now, after this new capital invention, we have more roles and fewer people in each of them. Exactly as predicted by the division of labour story!

But if we instead look at the tasks, we have more tasks per person. Instead of being able to specialise in one task, like tracking, each hunter must now undertake more than one task on average as there are only two hunters available for three tasks—the same for our gatherers. What we see as specialisation in roles is the automatic result, not the cause, of increasing productive capacities.

What has happened is that the invention of new production techniques has allowed more tasks to be undertaken by each person leading to fewer people in each role.

Here, we again see that it is the nature of capital that defines both roles and available tasks at a societal level, just as within a pin factory the nature of the capital equipment defines the roles and available tasks.

At the macro level, the most productive countries are not full of people doing repetitive narrowly defined non-skilled tasks, but highly educated people doing specialist roles involving a hierarchy of complex and interrelated tasks that require specialist capital and training to master.

So what?

Like many stories in economics, the division of labour as a productivity enhancer has been approached far too narrowly. There are many economic lessons in the story of the pin factory, and if we probed deeper we could understand more about what considerations determine the boundaries of firms, why firms are internally not structured around market principles, and other important questions about how we coordinate productive activities.

There is also a big question about the incentives to invest in new capital equipment and experiment with new technologies. Although economics has a focus on technology as a productivity enhancer, there is really limited coherent theory on what causes faster or slower capital investment. Had we taken a different lesson from Smith about his pin factory, perhaps our knowledge of capital investment incentives would be better today than it is, and we would likely understand the process of economic growth and productivity gain much better than we do.

So if I understand correctly:

Adam Smith:

The division of labour (specialisation of tasks) results in productivity gains.

Cameron's view:

Technology determines the division of labour and is the primary determinant of productivity gains. This requires capital investment, so capital investment is actually the key determinant of productivity. The entrepreneur who invests is the inferred beneficiary of the surplus productivity benefits.

My take on this:

One hundred years ago, a philosopher, Kropotkin, postulated that the ownership of technology by a ruling class allows the subjugation of labourers because of the need for bureaucratic coordination if the work is specialised, thus leading to entrenched inequality. Each technology is the result of generations of accumulated knowledge, and by right, ought to be available freely to all. Releasing technology to the masses could therefore spur revolution by allowing decentralised, local mutual collaboration, freeing labour from the domination of the ruling class.

If we consider this from today's perspective, the previous gains in productivity required expensive machinery and capital wealth. By contrast, the cumulative tools and knowledge of scientists, programmers, engineers, lawyers and academics are now freely available at our fingertips.

If we want to shed the shackles of inequality and are brave enough to imagine a better future for our children, it might be worth embracing these tools of the future while re-examining the wisdom of the past.

“There is also a big question about the incentives to invest in new capital equipment and experiment with new technologies.” No. No there isn’t. Private capital has traditionally been reluctant to invest in industrial capitalism, preferring, as in the nbr today, to invest in economic deadweight like watercares monopoly debt, or second hand residential mortgages.

As Adam Smith makes clear in the (memory holed) books 4 & 5 of the wealth of nations - the sovereign should invest in that which the nation needs and that the individual cannot afford.

The sovereign. With sovereign debt/public credit/public issue, or windfall taxes, whatever you like. But the sovereign should ensure that the nation has what it needs. Through the virtuous and prudent use of its sovereign tools.

Instead? We are run by banksters. That’s not how capitalism works. That’s how racketeering and oligarchy works