A time for reflection: Life, property, adventure

My Dad, Keith Murray, lived 72 good years before he died on the 8th of May 2024.

The Great Housing Hijack was dedicated to him.

This week, as I reflect on his life, I want to share a couple of stories.

The first story is about property investing. Dad wrote to me to explain how he got into property investing before I was born. I didn’t know these old stories from the 1970s until recently.

The second is about adventure. Dad made a point to get out and see the world. And I think that one event in his life was pivotal in maintaining the inspiration. In 1977, in unusual circumstances, he met Colin Quincey, the first person to ever row from New Zealand to Australia. They became lifelong friends.

Here’s a photo of me with Dad on a 5-day hike in 2015.

Thanks to my paid subscribers. Please consider upgrading to support FET. That gets you access to articles like this one on Patient Property Owners, and the audiobook of The Great Housing Hijack starting at the end of the month.

I also have a YouTube channel where I collate my various interviews and presentations. Please subscribe for free to that channel here.

Property investing - Dad’s story

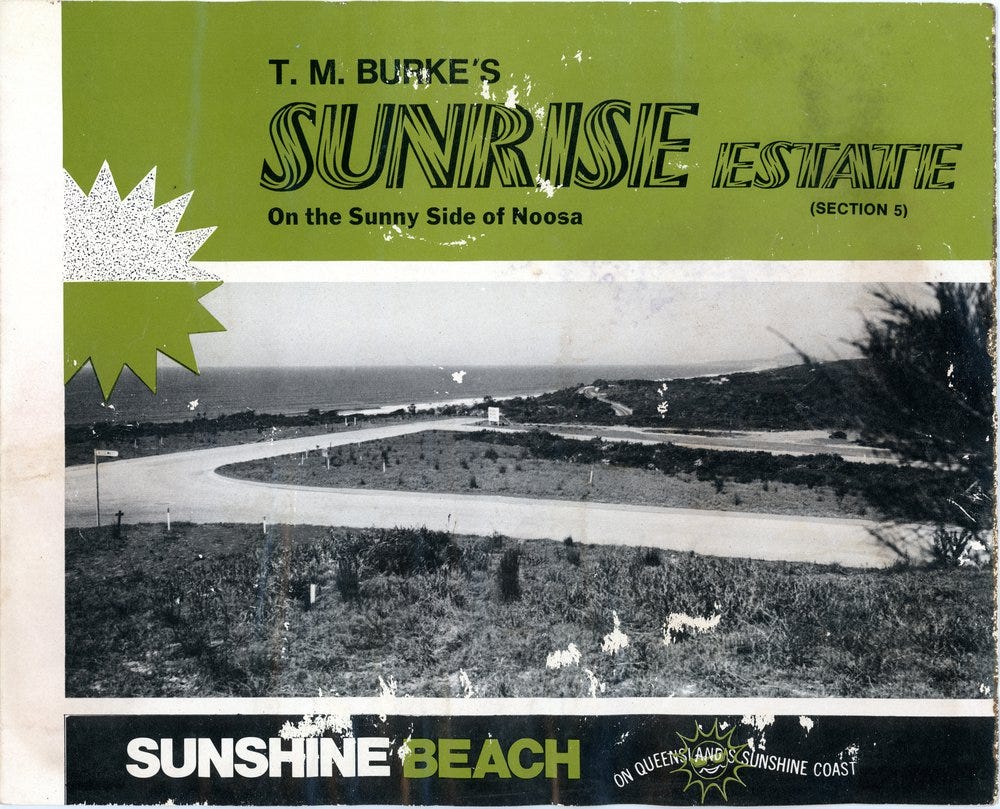

When Mum and I moved to Peregian Beach in mid-1975 it was in the middle of nowhere. The whole of the area between Noosa and Coolum was a disused army artillery range and was leased and then sold to developer TM Burke from Sydney.

They put in basic narrow streets, power and water and set up four or five sales caravans beside the main road between Coolum and Noosa (TM Burke built this road).

The land was offered for sale from these caravans on a hire purchase arrangement of about a $25 deposit and $5 per month from the late 1960s (these aren’t the exact figures, but they were very cheap).

Lots of people signed up while on holidays from rural Queensland and interstate.

I may have told you this story—Warren was a young surfer who signed up for an absolute beachfront block from a sales caravan back in 1970. He sold it in 1982 and bought a ski boat—not a great trade in retrospect.

When we got there in May 1975 real estate was dead. I had no clue about buying a house and your Mum got us looking. We couldn't find a house, so we scrimped and saved and told a few lies and bought a block of land at Marcus Beach which we then used to borrow against and build our first house.

This was when I learnt my first property lesson. The Victorian guy who sold us the house block also tried to sell us the block he owned in front of ours, so a double block. I said “No thanks!”

Then a year later when I realised my mistake I tried to buy it for the same price and he'd sold it the previous week!

Jump forward to 1977 and there were no pubs or shops anywhere and the social hub on a Friday night was the local bowls club at Peregian. There was a builder about 15 years older than me who I discovered was making very good money (the local RE agent tipped me off about his strategy).

The shine of having land and perhaps a future holiday house at a Queensland beach had worn off for a lot of people who had signed up from the sales caravan guys. They were trying to stop paying rates and maybe get some money back or break even by selling cheap—like the block Mum and I bought for our house at Marcus Beach.

This older builder guy would buy these blocks at distressed values, build his standard 2-bedroom duplex on it, and virtually double his money!

So I found a distressed land seller and built a nice duplex at Marcus Beach.

There was no CGT till 1985, just some very vague and ambiguous tax rules, so when I sold it in 1981 I doubled my money and used the profit to pay off my house mortgage completely by age 29.

I bought and sold four more blocks of land at a tidy profit. One on the side of Mt Coolum was a dud. It was too steep and I lost a little money on that one. I couldn't finance a build on the other four because Mum had stopped work and we were now a single income unit.

We moved to Brisbane at the end of 1985, sold at Marcus Beach in late 1987 and bought Finsbury Street straight away, virtually sold and bought for the same price. So we still owned Finsbury Street mortgage-free. In early 1988 tried to buy the house across the road on a 1200sq m block. I had finance sorted and was ready to go in with an offer on a Monday, but then John bought it over the weekend.

The other projects were the townhouses at Grandma’s in 1993, the Market St house in 1994, and Jean St in 1996. The rest of the houses you know.

Adventure and inspiration

Below is an excerpt from Colin Quincey’s book Tasman Trespasser describing his late-night landing at Marcus Beach in April 1977 which was the start of a lifelong friendship with my Dad (Colin himself died in 2018. His son Shaun rowed the reverse direction from Australia to New Zealand in 2010 to be only the second person ever to row across the Tasman Sea).

—————

With those words I closed the log for the last time, put it back in its Tupperware box and meandered slowly back up the beach to place it with the rest of the gear, now rapidly becoming covered in wind-blown sand. Bits of equipment still littered the beach but I left them. The water containers were dark blotches along the waterline stretching out either side of the boat. Looking to the north, tantalizingly close, but in fact several miles away, were the warm, welcoming lights of Noosa crowded on a dark headland. To the south scattered glowing windows blinked in the dim distance and between these two sources of help the great ragged ribbon of surf beating at the sand. I turned to face the back of the beach and the dunes, then scrambled up the twelve-foot slope to seek a way through, for I was sure there must be a road linking the lights and houses I had seen.

I could feel tufts of straggly grass between my toes and enjoyed the first earthy smells of the dense vegetation as I reached the top.

There was a road for I was able to see three or four street lights marking its path and the probing headlights of a car as it swept by.

However, between me and the road, stretching either way for as far as I could see by the light of a watery but rising moon, was thick, black bush. I worked my way into the bush through apparent gaps but was unable to make more than a few feet of headway.

After some twenty minutes of prodding and pushing against these unyielding guardians of local civilisation, I became disheartened and, nursing my scratched arms, slid back down the dunes to the beach. I suddenly felt very lonely on this inhospitable shore.

Having accepted the solitude for so long, now that people were close I urgently wanted to see them and talk to them - and hear them talking to me. It was reassuring to see TT [Tasman Trespasser, his boat], my home, squatting complacently above the waves, her little masthead light still contemptuously glaring at the sea. Her apparent pride and cheekiness encouraged me and I hardened my resolve to ensure she would be saved a further battle with the rising tide. To lighten her some more I disconnected the battery and heaved it into the sand. Then, looking up, came face to face with a very miserable, bedraggled koala bear, still clinging grimly to the mast. I ruffled his scruffy, soggy head, cut him down and stuffed him away in a pocket.

I'd been on the beach for over an hour by the time I set off for the second time to find a way through to the road. This time I went to the left and was almost immediately rewarded by discovering a clear, sandy path only a few feet from my starting point. I walked through the tunnel of overhanging trees for about a hundred yards and came to a tarmac parking area. To my right was a high blank wall; a quarter of a mile ahead of me the street lights fringing the road and to my left the relief and beckoning lights of an occupied house.

The road was hard to my softened feet and my left leg growing fatter by the minute, but by now I was rapidly regaining the familiarity of being upright and not having to hold on. As I stepped towards the house I worried about what the reaction might be to my extremely scruffy and unkempt appearance and wondered what on earth I should say. Stopping under a street light I combed my hair with salty, wrinkled fingers and brushed some of the blood and sand from my legs. Would it be funny talking to people again?

I still hadn't resolved my opening line' as I pulled myself up the wooden steps of the house onto a broad verandah to face the open, but curtained door of a lighted room. Apparently, nobody had seen or heard me, so I stood back, munched some raisins that I'd brought from the beach and, squinting in the unaccustomed harshness of the light, absorbed the scene in the room before me.

On a chair to my right sat an elderly man engrossed in the television, quietly droning at him from the opposite side of the room. His wife, or so I assumed, stood to the rear and left of the room, busily ironing at a board, and directly facing me, dressed in a bathrobe and slippers, a friendly-faced pretty young woman sat on a sofa. Thesitated, slightly nervous and not wanting to disturb such a cosy family scene, but I knew I had to, so stepped forward into the light and knocked on the wooden door frame. Everybody started including myself, and then the whole scene just froze.

Disbelief, anxiety, suspicion, fear, were etched into petrified faces. The iron in the woman's hand was held absolutely motionless in the air. A slipper swung to stillness from a startled foot. Only the television continuing its dreary commentary and the distant roar of surf disturbed the silence. Eventually, though it must have been but a few seconds since I knocked, I spoke. My voice sounded intrusive and loud.

"It's a long story, but I just landed on the beach from New Zealand — in a rowing boat — may I use your 'phone? Could you help me? Has anyone got a cigarette?"

A long pause and I tried to look as harmless and friendly as possible.

"No!"

I felt like apologising and going away but now a tall, bearded man was entering the room from the back, rubbing sleepy eyes. This relaxed me a little as his young strong presence had the effect of slightly easing the tension in the staring faces. He regarded me cautiously as I repeated my story, adding more detail and explaining that the boat had to be moved before the tide came in.

I was invited in and it was explained that the initial, defensive

"No!" that greeted my first enquiry, had only been in respect of cigarettes - they were a non-smoking family. The older man, very astutely, asked to look at my hands but that, of course, proved nothing as there was not one callous or blister, only scratches from the bush and the sores on my wrists. More positive but polite questions followed and slowly suspicion and incredulity melted into a tentative belief as somebody remembered 'reading about it in the paper'. There was still however considerable wariness in the faces around me, and understandably so as I discovered later, for some convicts had escaped in the local area only the day before.

I obviously didn't know this at the time and so to allay their doubts and because I was becoming more and more anxious about the boat, I suggested that they first accompany me to the beach to

'prove my story' and having done that, call the local police. This was agreed and so, torches in hand and with me directing a flow of what I hoped was a reassuring explanation at the young man, he and I returned down the sandy path to the beach. TT was still in the same place but beginning to be pummelled and rocked by the advancing tide. Together we hurried over to the boat.

"You rowed all the way from New Zealand — in that?"

"That's right. My gear's up the beach somewhere. I'll show you."

Finding it, however, was not so easy for by now it was half buried in sand. We shone the torches around, my bearded friend slowly shaking his head and every few seconds staring at me with a puzzled expression. He could not, I thought, really believe it but nevertheless, immediately we had found and inspected some of the equipment, his suspicion was replaced by congratulations, concern for my legs and a willingness to do anything possible to help.

So, in somewhat unique style, began my friendship with Keith and Elizabeth Murray, and Elizabeth's parents, the older occupants of the house that night. Their subsequent hospitality and help, both immediately and during the two weeks I stayed with them, was unlimited, generous and exceeded anything I either expected or deserved. Their initial reaction to the frightening sight I must have been at their door was, on reflection, probably very similar to how I, or anybody else might have behaved in similar circumstances. Thoroughly sensible, calm but cautious — well that's how they appeared to me but, as Elizabeth assured me later, she felt anything but calm at the time!

Keith and I returned quickly to the house from the beach, for we now had a race against the tide. He reassured his family and wheels rapidly began to turn to sort everything out. I booked a call to New Zealand and then spoke to the local police. I don't think they believed me either for I heard something muttered about cows being able to fly', but they did say they would come up to the house. It was Keith's turn now on the telephone and I looked with amazement as he was apparently speaking to the local milkman.

He saw my look, winked and whispered, "Four-wheel-drive". I grinned my approval.

"What would you like to eat?" asked Elizabeth from the adjacent kitchen.

"Anything, absolutely anything, as long as it's not dried or wrapped in polythene!"

A salad soon appeared, plus coffee and cold, fresh beautiful milk. I was still full of energy, answering questions and not finding it at all peculiar in the company of people again. In fact I thought it much the same as making the first conversation after waking in the morning.

I'd barely had time to finish the meal before about eight guys, a Landrover and several cars arrived outside. With a few short words of explanation from Keith, the group split up and one team, crammed in the back of the Landrover disappeared down the road to find an access track to the beach. I left brief instructions with Elizabeth's mother concerning the call to Auckland and then, laden with an anchor and lines collected from the garage, joined the rest of the party going back to the beach.

With half a rugby team, the Landrover pulling and the oars being used as runners it wasn't too difficult to haul TT up the beach away from the still crashing seas, and secure her to a tree. As much equipment as could be found was loaded into the back of the Landrover and I, now satisfied that IT was finally beyond the reach of the tenacious Tasman waves, hobbled back to the house on tired legs.

The police were on the scene when we got back, but the only thing I can clearly remember about them was the fact that they smoked! I sat down on the garage floor to relish the first puffs of this long-awaited 'fag' and was told later that I had a stupid grin all over my face as I did so. Having been assured that landing formalities could wait until the next day, we asked the police to say nothing to any press or media people. The fact that there was only one call from a newspaper that night is a compliment to their diligence in adhering to my request against, I later found out, quite a barrage of calls to the police office.

While we were on the beach the call to Auckland had come through and Dick and Norma, roused in the middle of the night, were informed that both the boat and I were alive and well in Queensland. They, in turn were to spend hours on the telephone to sponsors, friends and the media and had arranged a return call for the following day.

Thus, together with Keith, his family and the rest of the guys who had helped I was at last able to sit down, relax and enjoy yet another 'first', for the inevitable case of beer, much to Elizabeth's disgust, decorated the centre of the lounge. After only two glasses of this I felt quite dizzy.

The party 'broke up' at about midnight and I spent a luxurious few minutes in a hot bath, examined a rather ugly looking pair of legs and finally sank blissfully into a soft, clean, exquisitely dry and above all, unmoving, bed. A still-wet little furry bear stood guard on the windowsill, sharing perhaps my confused feelings of peace, of safety — of sanctuary after sixty-three days and seven hours of uncertainty, danger and doubt.

I am sorry for your loss - I have lost my parents over a decade ago and unfortunately I can't assure you that the feeling ever goes away. The passing away of prior generations really sharpens just how different he life opportunities the post war generations had. I gave SEQ a go but couldn't take root, but even in the early 90s there was plentiful housing there, my family were part of the great Victorian trek North.

The current housing dynamics feel very similar to the historical enclosure of the commons. Land that was in the past free for all was taken by those who had the means into exclusive service of their own wealth. And everyone else became a tool to serve their wealth accretion through labouring for someone else. An entire generation is being brought up to be rent fodder basically.

Beautiful words Cameron, sorry for your loss.