What an economics experiment taught me about corruption and human nature

All social games that steal from the collective pie require coordinating with your mates by repeatedly exchanging costly favours. This article is a lesson and a warning.

Every day, we hear details of fraud and scams—whether it is gaming the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), the now infamous daycare subsidy frauds in the United States, or “jobs for mates” situations where government boards and agencies are stacked with connected people as a way to siphon money to them.

These are not sideline issues. Dealing with them is a central problem for sustaining a productive and cohesive society. To sustain this society, we need to differentiate between negative-sum transactions and positive-sum ones. Then, we must ensure a system of oversight and enforcement prevents as many costly negative-sum transactions as possible. This is a fundamental requirement for economic growth.

Trading favours is a natural human tendency. We have evolved cooperative brains that can generate an amazing amount of productive human cooperation. But these same brains help us to cooperate via informal favour trades amongst a few people to impose enormous costs on the rest of society.

I spent my PhD years from 2012 to 2016 studying the economics of political favouritism. The back-scratching process I uncovered was dubbed the Game of Mates, which is the title of my 2017 self-published book with Paul Frijters, documenting political favouritism and its costs over the past couple of decades in Australia.

In 2022, that book was revised and updated and released under the new title Rigged.

The central problem of the Game of Mates is the conflict between allocating the resources of society in a way that maximises total value to society, or total value to a subset of society who might repay you in the future for that decision.

It is a game of back-scratching played on social credit. This is why the revolving door between regulators and the regulated is so common.

Studying back-scratching in the wild faces a major problem.

Favours are almost impossible to objectively observe. Not only is there a powerful incentive to conceal favours, but determining the ‘no favour’ counterfactual is almost impossible. Was the government contract given to the most efficient firm? Or was it a favour to the winner because an alternative bidder could have delivered a better outcome for the price? More often than not, we just don’t know.

One way I studied this process was by creating a computer-based experiment and recruiting hundreds of student participants to play it.

Studying back-scratching in a controlled experiment, while sacrificing realism, allows a close examination of the fundamental cooperative processes at play. In fact, I have played this game in the classroom many times, and it helps teach students about how difficult and unnatural it truly is to make decisions in the interests of society as a whole.

There is a long history of cooperation games in social psychology and economics. The ‘big new things’ I could do included seeing the emergence of alliances (often multiple ones), measuring the costs of back-scratching against an efficient counterfactual, and testing some institutional designs that might discourage or curtail back-scratching.

That experiment is published here. You can download a copy below.

Today I will explain the game and describe the lessons I learned.

In doing so, I will show that political favouritism is not a selfish game played by evil people, but a pro-social cooperative game that often feels good. This is why it is so hard to create and sustain institutions that harness our human nature for positive-sum cooperation while avoiding negative-sum cooperation.

The back-scratching game

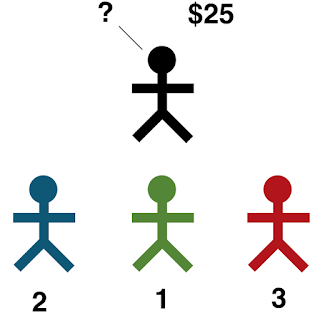

The basic experiment has four players in a group (the minimal number for an in-group and out-group to form), with one player able to choose which of the others to receive a prize of $25 in a round (in experimental currency). The player who receives the prize allocates a fresh $25 the next round to one of the other three.

If this were the whole experimental design, the best thing to do would be to form a back-scratching alliance with one other player and trade the $25 favour back and forth. Over 25 rounds, an alliance pair would make $625, while the other two would make nothing.

What makes back-scratching costly in my experiment is that each of the potential recipients of the prize is given a randomly shuffled ‘productivity number’ each round, either 1, 2 or 3. This number determines an extra payoff for every player for that round, in addition to the $25 directly allocated.

Give the prize to the player who has a productivity number of 1 in that round, and the group gets $1 each. Give the prize to the player with 3, and the group gets $3 each. Think of this productivity number as reflecting the efficiency of firms competing for a government contract. It represents a conflict between choosing what is best for the total society, and what is better for a single selected other person.

The best thing to do for the whole group is to allocate to the player with a productivity number of 3 each round. That provides a total group payoff of $37 for each round ($25 prize plus $3 for each of the four players), and an average payoff to each player over 25 rounds of the experiment of $231.25.

With the extra payoff from the productivity of the prize-receiving player each round, this creates a cost to taking the back-scratching approach and trying to reciprocate each round.

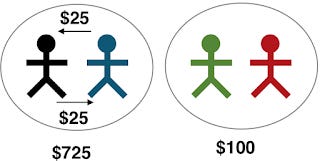

To sustain a back-scratching alliance means not choosing the most productive player for the prize in two-thirds of the rounds. Over 25 rounds, back-scratching earns the alliance $725 between them, or $362 each, a 57% higher payoff than the overall best strategy for the whole group of four players.

The outside group of two players not in the alliance earns $100, or $50 each.

But the total group of four players only makes $825 instead of $925. There is a $100 effiiceny loss. The economy is 11% smaller than it otherwise would be due to the back-scratching, meaning that back-scratching is a negative-sum exchange relative to the alternative.

I have run this experiment in a variety of forms with hundreds of groups, and also run it in the classroom with the productivity number given on a sheet of paper, with a group of four standing up at the front of the class, and the payoffs recorded on the whiteboard.

When I first designed the experiment, I was worried that the honest young university students who participated would rarely see the opportunity to form a back-scratching alliance, let alone act on it.

But in fact, most groups did see alliances form, even if just for a few rounds.

I paid the participants in real money, as is the norm for economics experiments (rather than experimental currency). Typically, alliance pairs reduced the benefit to others of AUD 30 to increase their alliance earnings by AUD 20 during two experiments totalling 50 rounds. That’s a social loss to the whole society of AUD 10.

Surprisingly, alliance players were happy about their actions.

They thought they had been cooperative and helpful by doing their mate a favour, and didn’t feel guilty about the costs they imposed on others. They also rationalised their behaviour, saying that forming an alliance is a justifiable strategy, while also concealing it by lying when explicitly asked in a later survey if they had formed an alliance.

I tested two institutional changes in the experiment.

First, a staff rotation, a common anti-collusion policy. This was enacted by reducing the probability of the player receiving the prize being able to allocate in the next round. This was somewhat effective when the experiment began with this policy, but not so effective when it was implemented after alliances had formed. In this scenario, the alliance pair and the outsiders simply took turns at favouring the other person who had previously emerged as their own partner.

Second was a low-rent policy, mimicking bureaucratic procedures to limit the size of prize able to be allocated with discretion. This was enacted by reducing the prize so that instead of $25 per round, it was $3. Again, this was effective only when part of the initial experiment, not after alliances had formed. Despite there being no financial advantage from continuing an alliance with this small prize, because there was a risk of losing power to the other two players, the inefficient alliance continued.

The fact that neither was particularly effective at stopping back-scratching, and at best only at preventing it from emerging, indicates how difficult the challenge of eliminating negative-sum exchanges in our political and governance systems really is.

Some observations from these experiments are:

Loyalty is strong. Rotation policies are good, unless those people being rotated in have existing loyalties. This means there is a trade-off for regulators; staff with more industry experience are also likely to come with stronger prior alliances and hence be more prone to back-scratching. In politics, it means voting in a different political party brings with it the alliances of that party.

Bureaucracy can work. The array of internal procedures emerging in our large private organisations could come from seeking internal fairness and firm-level optimisation over favouritism within the firm.

Social norms are strong. In organisations or groups where some people are observed doing the right thing for the group, this quickly becomes the norm. Whereas, where favouritism is observed, the group descends into counterproductive back-scratching unless this is quickly punished. In some groups, I could observe them first cooperating, then forming an alliance, then if they got control, the others punishing that alliance for a few rounds with an alliance of their own, and then returning to the group cooperation.

Be loyal, but not too loyal. If your alliance partner fails to come through with favours when expected, it pays to look for someone else whose back needs scratching.

None of this is really rocket science.

If this sounds obvious to you, then you’ve probably learnt a lot about human behaviour through life experience. It also means the experiment is capturing important elements of real phenomena.

So what?

After spending three years researching this topic, of which this experiment is a small part, I have concluded that group formation through favouritism is a core determinant of political outcomes. The trick for business, government, and politics is to set up rules and enforcement mechanisms that catch this negative-sum cooperation and favour-trading and set the example of norms that maximise benefits for all.

To return to the deep insight into human nature, we are evolved cooperators, but usually only with a small, identifiable group, not with an abstract notion of society or the country at large. Joshua Green explains the evolutionary basis for this.

Morality evolved to enable cooperation, but this conclusion comes with an important caveat. Biologically speaking, humans were designed for cooperation, but only with some people. Our moral brains evolved for cooperation within groups, and perhaps only within the context of personal relationships. Our moral brains did not evolve for cooperation between groups (at least not all groups). How do we know this? Because universal cooperation is inconsistent with the principles of natural selection. I wish it were otherwise, but there’s no escaping this conclusion

It is not about bad people. Corruption is about good, pro-social people, who feel good about doing their mates a favour—after all, surely what’s good for my mates is good for society, right?

This is why minimising corruption is a perennial economic, legal, and political battle.

As always, please like, share, comment, and subscribe. Thanks for your support. You can find Fresh Economic Thinking on YouTube, Spotify, and Apple Podcasts.

Interested in learning more? Fresh Economic Thinking runs in-person and online workshops to help your organisation dig into the economic issues you face and learn powerful insights.